Mary Berry’s dependable The Aga Book — a book of the last century and part of my kitchen library — is full of the good sense of a domestic science instructor. There’s little hint Mary would later be crowned glam granny celebrity judge on TV’s The Great British Bake Off; neat as a pin in floral jacket, tough but twinkly, fair but firm. The iron hand in a pastry glove. Post-Bake Off, she is still unstoppable. There has been a surge of cookery programmes, accompanying hardbacks and further explorations into her life, her garden, her travels — recently being zoomed around Rome on a motorbike. Wherever we turn, there smiles Mary, instructing us beneath eyelashes rivalling those of Barbara Cartland. Extraordinary in the ordinariness that the British adore, viz Delia.

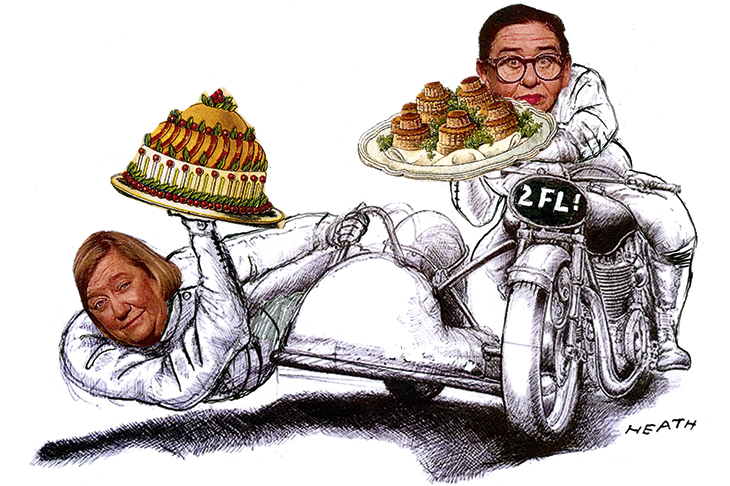

But cooks on motorbikes are not new. In the 1990s, two middle-aged mavericks in black leather, goggles and helmets rode on to our screens, on the saddle and in side car. Jennifer and Clarissa had a passion for cooking, respect for tradition and authenticity — but scant regard for correctness and conformity. Where did these comely cuisinières provocateurs spring from?

A talented TV producer, Pat Llewellyn, discovered Clarissa Dickson Wright demonstrating the cultivation of an unspeakable vegetable called a cardoon — with a certain panache — on her allotment. Clarissa was then co-owner of specialist shop Books for Cooks. For Pat, she sparked the notion of a fresh genre of character-led cookery programme, with the hosts engaging with the audience through chat to each other. In Jennifer Patterson — food writer and cook at The Spectator, who went to work on her motorbike — Pat found the ideal other half and persuaded the BBC to make a series.

They became Two Fat Ladies — a mischievous duo who brought fat into fashion without shame; demonstrating recipes, mincing meat but not words, full of sauce and spiked with wit, once quoting a far less cuddly culinary predecessor, Fanny Cradock (God!), with her advice on achieving good pork crackling: ‘Rub salt into the fat as if into the face of your worst enemy.’

South Kensington Jennifer turned up in my life in the mid-1990s, arriving at our Northumbrian farmhouse for a summer lunch having driven over the hills from Cumbria with her weekend host, Patricius Senhouse, from his ancestral home, The Fitz (now a smart hotel) in Cockermouth.

Jennifer was resplendent in turquoise kaftan and matching trousers, one of a set she had made to order in India in a rainbow of colours. Her blacker-than-black hair was pulled back into a knot; immaculately lacquered toenails peeped out of her jewelled sandals. ‘What beautiful roses you have,’ she exclaimed at my brimming bowlful. ‘Do you have a garden in London?’ I asked tentatively. ‘No darling, just a fire escape,’ she responded, lighting up a king-size and clinking the ice in her vodka on the rocks.

There was no chance of a quiet party or a brief event with Jennifer. That would be missing the point of her presence. She was — on the surface at least — warm, funny, bountiful with anecdotes and with a tendency to burst into song after the main course in a rich contralto. No one minded what she sang — or said, even when she patted a diminutive guest of ours on the head, exclaiming: ‘So sweet, just like a tiny little pixie.’ The guest’s mischievous terrier got his own back — when Jennifer sat down, he jumped on to her and bounced from voluptuous mound to mound, giving her a tiny nip along the way.

I was chuffed when, later, she commended a dish I had served at luncheon in The Spectator. She paid the compliment again another year when she came over to lunch. But the first time, as now, was Easter, and bless her, she wrote: ‘I have a very joyous first course for you, suitably festive for Easter Sunday, pretty and pink to precede your paschal lamb or bunny. I first had this served to me in Northumberland by Jane Torday and thought it a dream.’ It was, as I told Jennifer, based on Rick Stein’s terrine of lemon sole, prawns and fresh herbs with a prawn sauce — from his first book, 1988’s English Seafood Cookery.

But all good things come to an end. Not young, Patricius died before the 20th century’s end. He was a gay of the old school —not easy in the rural hinterlands of the north — but after the death of his mother, he enjoyed a long relationship with a carpet dealer from Carlisle. Jennifer came up from London for the funeral, a devout Roman Catholic in her a black lace mantilla. On this sad occasion, she wasn’t entirely kind about Patricius’s partner, who was present — entirely on account of his social status.

Afterwards, we gave Jennifer a lift to the station as she intermittently swigged chilled vodka from her flask. ‘The best Russian, darling, I alternate it with Sainsbury’s,’ she chortled, before bursting into a full rendition of ‘Just One Of Those Things’. Sadly, Jennifer, ‘one of those bells that now and then rings’, would not have all that long left herself — until August 1999, from cancer, to be precise.

The world became a duller stage when the dramatis personae of Jennifer — and in 2014, of clever Clarissa too, by then a tireless campaigner for quality, locally sourced food — no longer strutted the scene. Neither of the Fat Ladies had the easiest of childhoods, but they were full of what my mother would call ‘dash and go’ — focused on food and laughter as incontestable forms of survival.

Pat Llewellyn, responsible not only for Two Fat Ladies but also Gordon Ramsay and Jamie Oliver, was, in her fifties, diagnosed with cancer too. She died in 2017, far too young. It was the recent annual Pat Llewellyn Radio 4 Food and Farming Award that cast my mind back to different days of amusement in the last century.

What remains the same? After a long day, there are still those among us who relish fantasy, inspiration and comfort from great food programmes. Now, there are new, young, talented, informed, innovative — often international — cooks, who can cast a spell over us, with their recipes, dreams and stories. We need to charge up our batteries by learning more about them — and be fed less of the incessant profiling of the lives behind other, over-familiar faces.

As our country spins out of control, let us at least be inspired to take charge of our own kitchens; even just to toss a salad feels empowering when living under a regime of a hash of tossers. Yes — Jennifer and Clarissa would have had plenty of pithy views to express about that.

Terrine of lemon sole with a prawn sauce

To make eight portions of terrine, you will need:

8 oz (cooked) prawns in their shells

8 oz skinned lemon sole fillet

1 medium egg

Half a small onion, chopped

Salt

8 fl oz double cream

1 tsp chopped chives, parsley or both

For the sauce:

Shells and heads from the prawns

1 tsp tomato puree

1 small onion, chopped

1 small stick celery, chopped

5 fl oz double cream

Juice of half a small lemon

Pinch cayenne pepper

Method:

Start with the sauce. Peel the prawns and reserve them. Put the heads and shells in a saucepan with the tomato puree, onion and celery. Cover with water, bring to the boil, then simmer for 25 minutes. Liquidise and pass through a sieve.

For the terrine, make sure all the ingredients are cold before starting. Place fish, salt, onion, lemon juice and egg in a food processor. Reduce to a thick, smooth puree. With the motor running, add the herbs and pour in the cream over 15 seconds. Fold the peeled prawns into the mousseline, then fill a buttered one-and-a-half pint terrine and chill for about 30 minutes.

Sit the terrine, covered loosely in buttered foil, in a baking tin half full of hot water. Cook in an oven set at Gas 4 (350F / 180C) for about 40 minutes. Check the terrine is cooked by pushing a thin knife or trussing needle into the centre and testing the temperature on your top lip – if it feels warm and has come away cleanly, it is done. (Alternatively, I cooked my terrine for six minutes in the microwave — brilliant for delicate fish, and this dish.)

Remove the terrine from the oven and leave it to stand for about 10 minutes before turning it out very carefully on to a warm dish of pleasant aspect. Then back to the sauce. Heat the sieved prawn stock, adding the 5 fl oz double cream, and reduce the volume by bringing to a rapid boil, until you have a sauce which will coat the back of a spoon. (I find a dash of cognac doesn’t go amiss.) Season with lemon juice and the cayenne.

Serve the terrine in slices with what some restaurants rather coarsely describe as ‘a puddle of sauce’. Note: the amount of egg white that goes into a fish terrine is critical — too much and the terrine becomes rubbery, too little and it won’t hold its shape. This one hovers on the edge of being difficult, but it melts in the mouth.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in