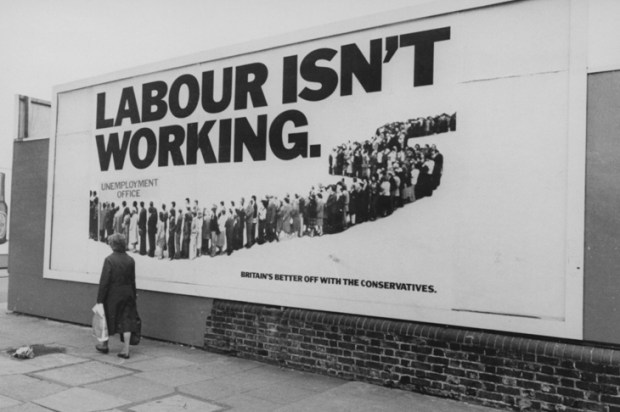

In the somewhat distant days of my early manhood rhetorical language – that is language designed solely to persuade or impress – was more or less the exclusive preserve of politics and advertising. Unless its target audience was especially obtuse such language was not even necessarily expected to be particularly convincing. In other words most consumers knew perfectly well that the fairly outrageous claims made for all the competing brands of toothpaste, say, were all equally unlikely to be true – yet such folk needed nonetheless to brush their teeth with something – probably chosen in the long run for a pleasantly designed carton and not too unbearable a taste.

In those happy days rhetorical use of language was not yet even remotely part of academic discourse. In fact, when my sole sibling attended University College London to read English her degree course was very little different from that followed there by my late father 30 years earlier. Thus all the historical allusions and lyrical beauty of Shakespeare’s language were still debated then in appropriately respectful, lucid and learned language. Indeed, one of the first quasi-academic areas to be invaded by virulently rhetorical language – with almost total success – was unfortunately that of my own original choice of career: visual art.

I was a full-time painter when my first book The Art of Self Deception (Libertarian Books 1977) took issue with this destructive and intellectually deficient use of language. By then the main subjects for artistic debate had become reduced to whether this object was more or less modern, advanced, evolutionary or ‘cutting-edge’ than that. Indeed, whole national and regional collections of art were purchased at that time for precisely those most unsafe of reasons.

The storerooms of the NGA and the AGNSW, for example, would amply bear me out on this claim if you or I were allowed entry to examine them. Proper scholarship and aesthetic evaluation were both sad casualties of modernism yet post-modernism subsequently had an even more destructive – if for a long time cleverly concealed – agenda: the destruction and replacement not just of Western culture but of Western civilisation itself. Have you not quite reached a point of realising this yet?

The Ramsay Foundation for one certainly should have done so by now but regrettably did not seem to grasp at first exactly what its esteemed staff were dealing with. Perhaps they should have cast their net a bit wider? That said I am lucky enough to possess a vast library consisting in part of the priceless illustrated catalogues of the often unrepeatable exhibitions of many of the greatest artists our world has seen.

When I have a moment I often pick up a catalogue at random. Today this was Gauguin and the School of Pont-Aven: Prints and Paintings – an intriguing exhibition shown at The Royal Academy of Art in London in the autumn of 1989 and the National Gallery of Scotland in following months. The show covered events in Brittany from exactly a century earlier and was of particular interest to me because of the similarities of Brittany to Cornwall where I lived and painted myself for about twenty years.

Brittany and Cornwall were also strongly linked by similarities in local language, human appearance and Celtic place names. I have stayed myself in Pont-Aven and know that whole area well. Yet how many people today know anything at all about Gauguin’s fascinating life before his final departure for the South Seas? I do not pretend to know how artists are trained in Australia these days but strongly suspect their training would not even begin to approach that available at various art schools in Australia before the outbreak of the second world war. But that’s progress for you.

Paul Gauguin was born in 1848, in other words 30 years after Karl Marx whose influence currently permeates education at every level in this country along now with much of our public life. The latter influence dates back to the 1960s when what we know now as ‘political correctness’ first picked up a favourable breeze and began its drift across the Pacific from a certain Californian university. For years no one probably understood exactly what they had on their hands here in Australia and thus unwisely derided or even temporarily forgot about the whole weird-seeming business of PC. But political correctness was, of course, just the thin end of a wedge which led eventually to subsequent, increasing control of our language and to our present utterly wrong and humiliating restriction of free speech.

Largely because I read widely I have long been aware of the likely dangers of post-modernism which have infiltrated public life in the West not via a single, obvious confrontation but through an unending series of cleverly deceptive cumulative steps. To those who understand what is happening properly this process is both sinister and a one-way street but too few people here fully grasp the danger of its nature as yet.

Do you perhaps recall the torturer’s speech in George Orwell’s 1984: ‘You believe that reality is something objective, external, existing in its own right… but I tell you reality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind and nowhere else.’ Those words describe precisely what was and is the core nature of totalitarianism.

1984 is surely coming to Australia and is currently running about 35 years late. So far, the traditional good sense of most Australians has managed to delay this process but never become complacent. Every single aspect of post-modernism is specifically designed to break down the fabric of traditional Christian democracies – usually via the pretence that the latter are somehow ‘backward’ or ‘out of date’. As was the case with visual art all of this is mere rhetorical nonsense. Never be fooled that where we are currently headed is ‘progress’ because humanity’s eternal truths will continue to remain happily exactly where they always were.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in