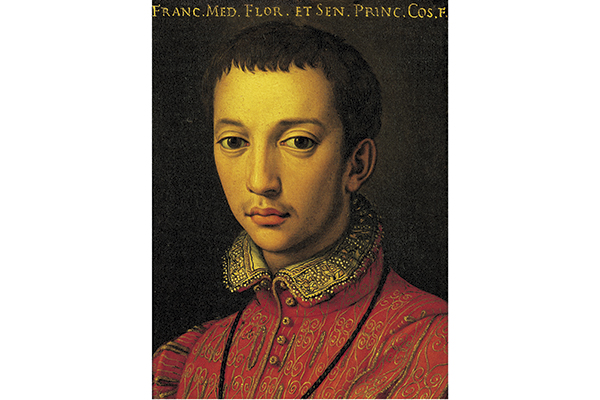

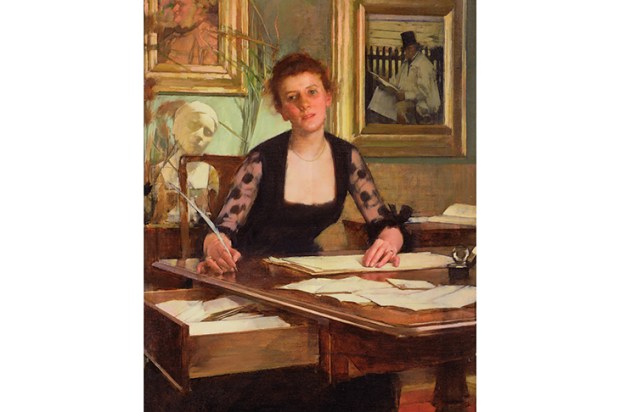

Agatha Christie’s spirit must be loving this poisonous new historical entertainment. Eleanor Herman has already enjoyed the success of Sex with Kings and Sex with the Queen, thoroughly researched, gossipy revelations of promiscuity among monarchs and their noble retainers during the Renaissance. She is an American author and broadcaster, born in Baltimore, now living in Virginia, but, at 58, she still concentrates her professional attention on the historic immorality and disastrous vulnerability of western European royalty.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in