A young girl finds the body of her nanny, brutally murdered, and the barely moving form of her mother, a second victim of the attack. The perpetrator of these deeds is the child’s father, who manages to flee the country and has never been seen since. This is the wound at the heart of Flynn Berry’s A Double Life (Weidenfeld, £14.99). Adulthood has given Claire Spenser no respite from her pain. Haunted by the horror she witnessed as a child, she now obsesses over every scrap of information about her father. She investigates his close friends and family, suspecting them of helping him to escape trial. But this isn’t a quest for revenge, more a personal search for justice, and above all, understanding.

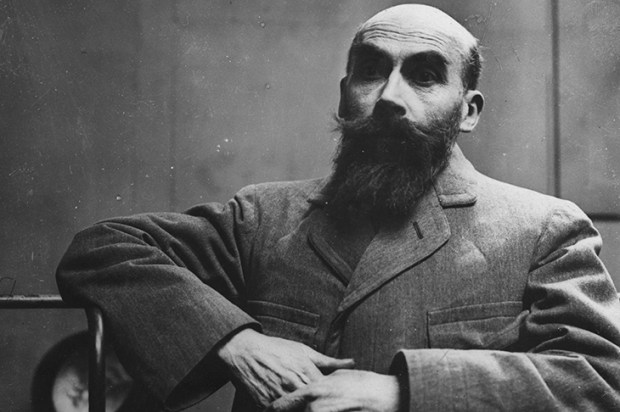

Richard Spenser is rich and privileged, and these attributes give him protection. There are obvious hints of the Lucan case, but Berry makes the story her own, weaving in details that snag at the mind’s edge. Claire lives only to settle the problem, and every emotion is filtered through that intent: it makes her a slightly enervated character, one-sided even. But understandably so. The story dances between rage and compassion. This struggle between opposing values propels the book to its startling conclusion.

Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £12.99) is an oddity: a crime novel set within a more expansive text that follows the thoughts and actions of Janina, an old lady who lives in an isolated Polish hamlet close to the Czech border. One night she discovers the corpse of a neighbour, a hunter nicknamed Big Foot. The police are satisfied with a verdict of accidental death, but Janina has a more startling idea: that the animals Big Foot was hunting had turned on him and somehow killed him in revenge.

This is a fierce book, an invective against cruelty to animals. Yet it’s peppered with weird bits of knowledge, some of them so bizarre that even a Google search leads to no clear yes or no answer. There are references throughout to astrology, another of Janina’s passions. Everyone sees her as an eccentric, well past her prime. But Janina proves otherwise in her doggedness, and her imagination. Her theory is bizarre, but the book does well to make you almost believe it. The ending allows that belief to take a sudden upside-down twist.

The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry (Canongate, £14.99) deals with the invention of anaesthesia and its uses in medicine and in crime. Set in Edinburgh in 1847, it charts the fortunes of Will Raven, a low-born medical student taken on as an apprentice by the renowned Dr Simpson. We get to witness gruesome depictions of births gone wrong, amputations and other makeshift operations. In counterpoint to this, a growing number of young women are being found murdered, their bodies frozen in their final pain, one of them being a prostitute that Will himself had been accustomed to visit.

Readers who delight in historical detail will take great pleasure; every page brings a new insight. Will’s relationship with Sarah, the Simpsons’ housemaid, is the heartbeat of the tale. She is strong and smart, and her growing love for Will is tenderly described as they work together to uncover the reason for the killings. Published under the pseudonym Ambrose Parry, the novel is a collaboration between the author Chris Brookmyre and the anaesthetist Marina Haetzman. I’m guessing that Haetzman is responsible for the descriptions of the interior of the human body as it’s being attacked, a surprising element that adds excitement, even as it makes you wince.

George Pelecanos’s The Man Who Came Uptown (Orion, £20) is a celebration of the power of the novel. Michael Hudson is serving out a prison sentence when he meets Anna Byrne, who runs the prison’s library service. She encourages him to join a weekly reading group. When Michael is later released onto the streets of Washington DC, he takes this newfound love of books with him. He buys a novel from a local bookshop and places it, a single volume, on a set of shelves he finds abandoned on the street: a symbol of hope. But then he gets dragged back into crime, blackmailed by a private investigator named Phil Ornazian, who moonlights as a petty criminal.

This is Pelecanos in his element: the story of a good man who makes a dire mistake, and then pays for it in more ways than one. Set against Michael’s struggles to resist the criminal life is his burgeoning relationship with Anna, away from the prison’s confines: a shared passion for books leading to possibilities beyond the page. The passages where Michael lies in his cell reading an Elmore Leonard western are heartfelt and moving: the story opens a window onto freedom. In its own particular way, this is an equally inspiring novel.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in