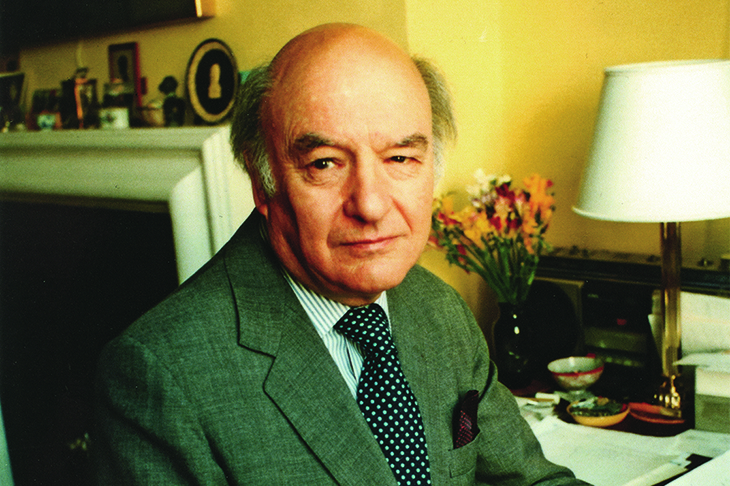

Kenneth Rose was gossip columnist by appointment to the aristocracy and gentry. He was, of course, a snob — nobody could write a social column in the Sunday Telegraph for more than 50 years without some snobbish instincts — but he was an intelligent one, singularly well-informed, and capable from time to time of administering a sharp bite to the noble hands that fed him his material. It might reasonably be said that his contribution to social history is limited in its parameters, but it is a real contribution for all that. It is also great fun to read.

Certain themes recur constantly in the course of his narrative. One of these is Eton. Himself a Reptonian — an institution little mentioned in these chronicles — he dismisses Harrow with contempt: ‘Quite the ugliest school I have ever seen, and such parents!’

To the Eton library, on the other hand, he presented several volumes and urged the librarian to visit his flat to ‘choose some Etoniana and other works’. When Harold Macmillan was appointed prime minister, Rose observed that he was the first Etonian King’s Scholar since Walpole to attain that office.

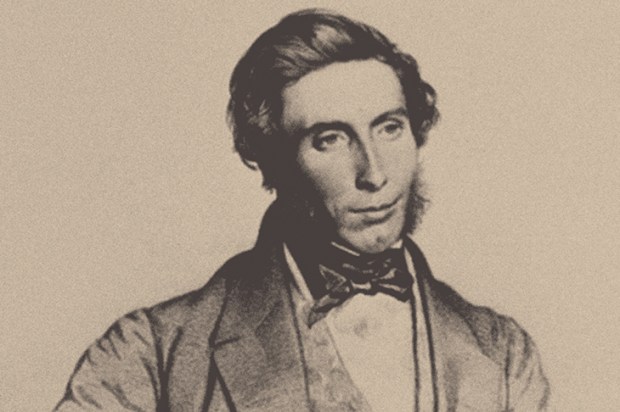

Rose has a good eye for colourful detail. At Hughenden, Disraeli’s former house, he noted that a copy of Leaves From the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands contained an affectionate inscription from its author, Queen Victoria — ‘but pages uncut’. In the dining room one chair had an inch or so chopped from the bottom of each leg so that the diminutive queen could rest her feet on the ground while eating.

By instinct he was a strong Conservative — it is unlikely that he ever considered voting for another party — but his support wavered at the time of the Suez crisis. ‘What an appalling week it has been,’ he told his parents:

I am sorry you think the government are justified. Personally I think they have not a moral leg to stand on. Whatever one may think of Gaitskell or Egypt is quite irrelevant. Either nations live by the rule of law or by self-interest. And in invading Egypt we have abandoned our entire moral foundation.

That same night he dined at the Beefsteak Club, the source of much of his most spirited gossip. Harold Nicolson, at the head of the table, ‘deliberately picks quarrel over Suez — he and I against the rest’. When the journalist and politician Bill Deedes dined with him a few nights later, Rose tried to ‘convince him of the government’s folly in going into Suez at this moment — not only folly but dishonour’. His efforts were unavailing, but he never doubted that his opinion was the right one.

Rose’s reactions were sometimes unexpected. When he read E.M. Forster’s The Longest Journey he remarked that it filled him with a deeper revulsion than even Howards End. ‘The style is too contrived and spinsterish, the situations absurd and the characters tiresome beyond belief. Oh, for a little red-hot sex in his books!’ Red-hot sex was not something that one immediately expected to be to Rose’s taste, but then neither was the left-wing politician Aneurin Bevan. Yet on the Suez crisis they thought as one. When Suez was debated in the House of Commons Bevan made what Rose considered ‘the best parliamentary speech I have heard since Winston’s last speech on defence’.

He found it hard to criticise, still less condemn, members of the Royal family. Lord Altrincham, as John Grigg then was, asked him to contribute an article on the Queen’s finances to a number of the National Review devoted to the Royal family. Rose refused: ‘It would be embarrassing to write familiarly of people whose hospitality one has enjoyed, and I should hate the process of spying and delving.’ (The next paragraph reads: ‘When Noël Coward, at any social gathering, wants to go to the loo, he always says “I must telephone the Vatican” ’ — an example of the sort of quirky detail which makes these journals so entertaining.)

But in the privacy of his diary, he could from time to time be mildly waspish, even about the Royal family (though perhaps not the monarch). After he and Coward had dined with the Duchess of Kent, he wrote:

The Duchess much the same as ever, still extraordinarily beautiful but never terribly interested in what goes on around her — and certainly never hesitating to yawn even in the middle of Noël’s best stories.

Kenneth Rose’s diaries do not make history and do not set out to do so. There are no significant revelations which will change the way we look at events or radically alter our judgments of important public figures. But they do illuminate history and give it life. If one cannot be there oneself then Rose provides as good an apparatus for eaves-dropping as can well be conceived. He deserves our gratitude.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in