The People are angry. In fact, they’re bloody furious. As the lights flash up on David Pountney’s production of Prokofiev’s War & Peace, the entire cast confronts the audience: grim, braced, defiant. And before you’ve had time to wonder if this sort of thing is just the long-term legacy of Les Misérables, or whether opera directors really are in love with totalitarian imagery, they unleash hell. This is the chorus of Welsh National Opera, after all. You just know they’re going to slay, and they do. The massive, world-historical Epigraph to Act One shakes the walls and your place is no longer to question, but to sit there and be overawed.

To be fair, a Soviet composer during the second world war could hardly get away with anything less. It’s clear that Prokofiev originally envisaged something like Mussorgsky and Borodin’s historical epics, in which tub-thumping grandeur is undercut by a mixture of intimacy and mocking, satirical humour. But the commissars kept knocking it back: sorry, comrade, it needs more Heroic Workers in Act Two. Prokofiev never saw a definitive production, and Pountney attempts — with some success — to straddle both visions, establishing a continuity between the aristocratic peacetime world of Act One, and the brassy, sometimes blackly comic all-out war of Act Two.

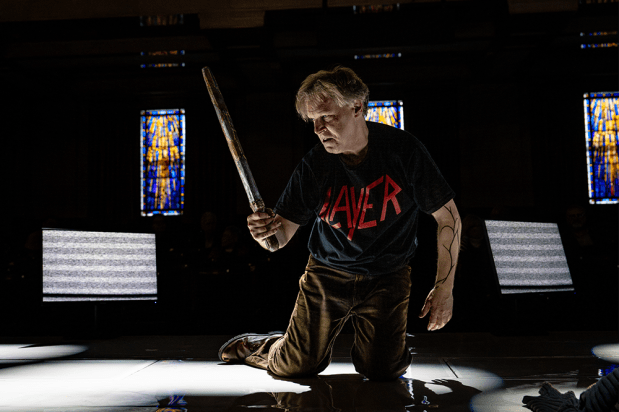

Robert Innes Hopkins’s timber-walled arena serves as the set throughout. A smock-clad Tolstoy wandered ineffectively through the opening scenes before vanishing behind his infinitely more interesting characters, clad by costume designer Marie-Jeanne Lecca in a mixture of Regency-appropriate ballgowns and uniforms (for anyone who had a name) or peasant frocks and vaguely first world war-era khaki (for the masses). Less helpfully, spectacular battle scenes from Sergei Bondarchuk’s 1966 film version were projected in the background. This is a smartphone century: if we see video footage we’re going to gawp at it, at the expense of the live performance.

Which, to be honest, is a bit tough on the individual performers — though with 22 cast members covering some 62 named characters this was unquestionably an ensemble achievement. Jonathan McGovern as Andrei and Mark Le Brocq as Pierre both made engaging romantic leads, the one measuring out yards of bronzed baritone with proud dignity; the other embodying bemused, awkward decency with a translucent, slightly tweedy tenor, though you could hear the purr of satisfaction from the audience when he broke Adrian Dwyer’s squirming cad of an Anatole. Lauren Michelle’s Natasha, too, was everything you could hope for: impetuous, and with an appearance of fragility that the controlled power of her voice belied. David Stout was as persuasive as any dramatic representation of Napoleon could be, but Simon Bailey’s Kutuzov stole Act Two. Craggy-toned, the old wardog lurched scowling about the stage with crutches and an eyepatch. There’s your Mussorgskian grotesquery right there.

But Pountney often characterises with a broad brush, and while conductor Tomas Hanus and the orchestra played with eerie delicacy in (to take just one example) Andrei’s hallucinatory death scene, you occasionally wondered just what Pountney was trying to say. In the programme, he preaches against ‘intolerant, dogmatic nationalism’. Cut to peasant girls briskly pitchforking wounded French soldiers, to jaunty music, and — weirdest of all — a troupe of machine gun-toting sylphs who pirouetted on near the end for a brief socialist ballet in the best Madame Mao style. Still, that WNO chorus, though. They could probably take Moscow with a single ‘Slava!’

The chorus of the Royal Opera isn’t in the same league, though their crowd and battle scenes provided some of the most stirring moments in the new revival of Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra. Elijah Moshinsky’s 1991 staging is a stone-cold classic and Michael Yeargan’s beautiful designs — which place a Piero della Francesca cityscape onstage, and wash it in Mediterranean light — make a superb frame for this magnificent if flawed opera. Henrik Nanasi conducted in big splashes of colour, contrasting the bronze-and-black world of the (almost entirely masculine) action with the lambent maritime glow (the opera is set in Genoa) surrounding the only named female character, Amelia — an ardent Hrachuhi Bassenz.

But the choral and orchestral phrasing could have been more taut (Pappano might have sorted that). The male leads were all perfectly decent, give or take some shaky intonation, and Carlos Alvarez’s mahogany-voiced Boccanegra traced a satisfyingly ambiguous journey from swashbuckling tribune of the people to broken, all-too-human tyrant. Good is not the same as great, though, and the lack of applause as set-piece arias came and went started to feel embarrassing. Overall — like the Royal Opera’s recent Ring cycle — it fell just short of the standard to which the UK’s best-funded opera company should expect to be held. ‘Feel something new’ is the current slogan at Covent Garden. Too often it feels more like ‘We’re number one, why try harder?’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in