Early on the morning of 6 May 1840, a young housemaid in a respectable Mayfair street discovered that her master, the elderly and mildly eccentric peer Lord William Russell, had been murdered in his bed. His throat had been hacked at like a joint of meat, slicing through the windpipe and almost severing his head. It turned out not to be much of a whodunit. Within a few days, a young Swiss-born valet in the house named François Courvoisier was taken away for questioning, and faced by a pile of circumstantial evidence eventually he confessed to the crime. The real question is why he did it.

The answer that shocked everyone at the time was that he was following the lead of Jack Sheppard, the thief and prison-breaker who had recently featured as the hero of a wildly successful novel by William Harrison Ainsworth, and then had become a cult hero with working-class audiences who flocked to see theatrical adaptations of the story. As late as 1851, Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor included an interview with a boy who claimed that he became a purse-snatcher after being ‘remarkably pleased’ by the glamorous life of crime depicted in one version.

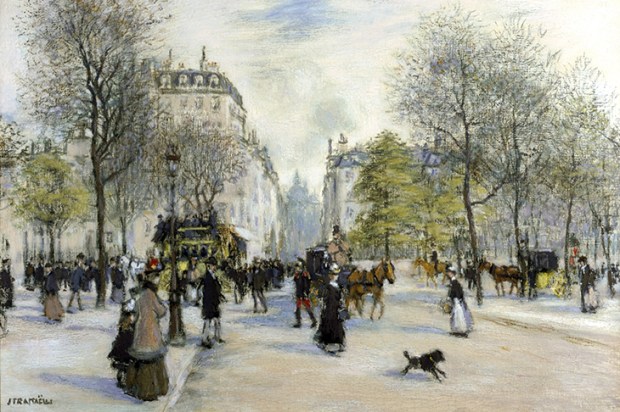

The idea that stories of crime might encourage servants to commit crimes of their own was especially disturbing to contemplate in the nervous political atmosphere of 1840, when working-class crowds often seemed to be on the verge of turning into a French-style revolutionary mob. Understandably, Queen Victoria followed the case of Lord Russell’s murder very closely, writing in her diary that it was ‘really too horrid’, but no doubt similar thoughts floated through the heads of many householders as they watched their maids quietly polishing the silver. After all, it was only a small step from slitting your master’s throat to sticking it on a pike.

Claire Harman sketches out this background in vivid and punchy prose, although in such a slim book she tends to skip over material that might complicate the main story. For example, she doesn’t dwell on the fact that the scandal over Jack Sheppard was part of a much wider Victorian debate over whether bad books really did encourage bad behaviour. Nor does she draw parallels with more recent debates over video nasties, where many of the same questions recur concerning whether the line between fiction and real life is a barrier or something more like a trail of breadcrumbs.

Where Harman does strike a chord with modern readers is her suggestion that Courvoisier’s chief concern after his arrest wasn’t whether or not he would be found guilty, but his own growing fame. Not only did he make an official deathbed confession, he repeatedly edited and added to it like a little novel in which he was both the author and the hero. Unfortunately his craving for celebrity — a word that had only recently taken on its popular modern sense — proved to be deadly. His execution outside Newgate prison was a social highlight of the year: the 40,000-strong crowd included several members of the aristocracy, as well as Dickens and Thackeray, who later confessed in his essay ‘Going to See a Man Hanged’ that the sight of one executioner tugging on the condemned man’s legs to strangle him ‘weighs upon the mind, like cold pudding upon the stomach’.

That was only the start of Courvoisier’s fame. Madame Tussaud’s made a waxwork from his death mask, before later displaying a model of his head under a glass case in the Chamber of Horrors, like a gruesome piece of wax fruit. Courvoisier also lived on through popular songs and later detective work, after the bloody handprint left on Lord Russell’s bed sheets inspired a Norfolk surgeon to suggest this might be a way to identify criminals — an early glimmer of modern forensic science. Today Courvoisier would probably have satisfied his ambition by hitting the gym and becoming a contestant on Love Island. But for a poor Victorian servant, it seemed the fastest way to fame was first to create a corpse and then to become one.

Meanwhile, the writer who had allegedly inspired Courvoisier suffered a rather different fate. If Ainsworth had also died in 1840, he might now be thought of as a writer like Byron: a literary star who shone briefly but brightly and left his readers wanting more. Instead, with each novel he ground out (some 40 altogether), he left them wanting less. He outlived his fame. In the 1860s, Robert Browning told Dickens’s friend John Forster that he had just met ‘a sad, forlorn-looking being’ who ‘reminded me of old times’. Slowly this shabby figure ‘resolved himself into — whom do you think? — Harrison Ainsworth!’ To which Forster replied: ‘Good heavens! Is he still alive?’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in