Prime Minister Scot Morrison’s Christianity has been under the media spotlight recently. All the reporting showed me that when people think of Christians and politics, they think of conservative culture warriors.

The self-appointed conservative champions of our culture will often speak about fighting against the ongoing threats to Judeo-Christian values in the West – its defence being a key animating force for their political activism.

The list of objections and grievances is familiar: radical gender theory, gender-neutral bathrooms, the Lord’s Prayer in Parliament, the silencing of traditional Christian ethics being expressed in public, calls for the removal of scripture in schools – signs for conservatives that the West is in danger of forgetting what it owes to Judeo-Christian ideas.

Far too often, these grievances read like a cry for victimhood status. A mourning of the loss of Christianity’s once privileged position and a yearning to be respected again by society.

When conservatives prioritise fighting a culture war, it reveals a failure to come to grips with the heart of the Christian ethic bequeathed to our culture – the call to love our neighbour.

In the Gospel of Luke, a lawyer asks Jesus ‘Who is my neighbour?’ Jesus’ shocking response is that we find our neighbour in the face of the enemy we seek to exclude. In the parable he tells, a beaten up Jewish traveller is ignored by two of his fellow Jewish religious leaders. It’s the Samaritan who aids him and spends a significant amount of his own money to nurse him back to health. Interestingly, the parable has a clear ethnic dimension. To understand it in the West’s terms, it would be like a beaten up white Australian being ignored by the diocesan archbishop, then the parish priest – but then being compassionately helped by the new Islamic arrival.

The primary ethical insistence that Christianity has bequeathed to us is this radical notion that we ought to have compassion for all – especially those society views the ‘least’ among us, springing from love for our neighbour, even when they don’t reciprocate. Seeking the good of others – the common good – even at cost to yourself.

Thus if the centre of the Christian ethic is the call to love our neighbour, then we can’t truly be said to be defending Christian values if we spend more time obsessed with modern alternative lifestyles than pleading the cause of the most vulnerable in our society.

Christians have drawn this from the example of Jesus himself. As St Paul put it:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a slave, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

Because Christians believed their God, rather than insisting on his own rights as God, was willing to shamefully humiliate himself for the good of others, they have insisted that they are called to do the same.

Christianity added another dimension to the Jewish idea of the Imagio Dei – for God himself had come down as a man, and shockingly, in the form of a slave. In ancient Roman law, a slave was non habens personam – without a face or image. For Aristotle, nature so clearly disclosed that some people were by nature more superior than others: some were born to be slaves and others to rule. Christianity insisted that God himself had identified with them and given them a face.

Where does that leave the culture war for Christian values then?

To seek the good of others including your enemy, even at cost to yourself, means that to defend Christian values can never be to fight a war to dominate or take back the culture. It can never mean an insistence that Christianity should hold privileged esteem.

Indeed, when conservatives engage in the culture war as a zero-sum game, where combatants insist that the public square must be captured with ‘Judeo-Christian values’ or else the secular foe will vanquish Christianity, they distract from the truly radical nature of Christian values.

Yes, let us commend our liberties and rights: and as a classical liberal, I certainly do. But the uncomfortable call for Christians is to be like their Lord; to prioritise the good of others over insistence on our own rights.

To defend Christian values to me is to continue to faithfully defend and proclaim the dignity and worth of all human beings, especially the least and forgotten among us, even in the face of a post-Christian society where people may forget and even despise religious liberty and the great contribution that faith has made to Australia.

I’ve been inspired by Liberal leaders like Mike Baird and his father (and Morrison’s predecessor as Member for Cook) Bruce, both practising evangelical Anglicans like myself.

During the height of the debate in the Howard era around our immigration detention policy, Bruce Baird was driven by his Christian values to call for a more compassionate and humane approach to the treatment of refugees, even abstaining from a vote to have all refugees processed offshore to pressure the Howard government to back down from excising the mainland – something later introduced by the Gillard government.

Bruce Baird summed up the Christian ethic in this way; ‘Christians need to use our power for those who have no power. We should use our influence for those who have no influence, a voice for those who have no voice.’

Later his son Mike as premier did what he could to create a more welcoming environment for refugees at the same time his federal counterparts were ramping up their rhetoric. He introduced travel discounts for asylum seekers, provided public service pathways for refugees, called for the Abbott government to increase their Syrian refugee intake and worked to enable more refugees to resettle in NSW.

In an Australia Day address, Mike Baird said ‘To shut our doors to refugees, as many here and around the world are calling for, is to deny our history, to deny our character.’ He also said ‘In a quest for personal comfort let us not sacrifice who we are above all, which is welcoming, compassionate and inclusive.’

Compassion for our neighbour should be the value that provides the driving, positive impetus for those on the centre-right who claim to want to defend the West’s Judeo-Christian heritage. It should drive our society’s progressive impulse; not merely to accept the way things are, but to dream of and work toward a world that is more dignifying to those who are currently marginalised.

Ultimately, any defence of Judeo-Christian values that isn’t a defence of the marginalised and the forgotten in our society is no defence of Judeo-Christian values at all.

For, after all, the great and scandalous insistence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, properly understood, is that every individual has great and profound dignity – including those that polite society would just rather forget about: The refugee long vilified as having no place among us. The welfare recipient whose background of family dysfunction places them in a vicious cycle of poverty. The Indigenous Australian yearning for justice.

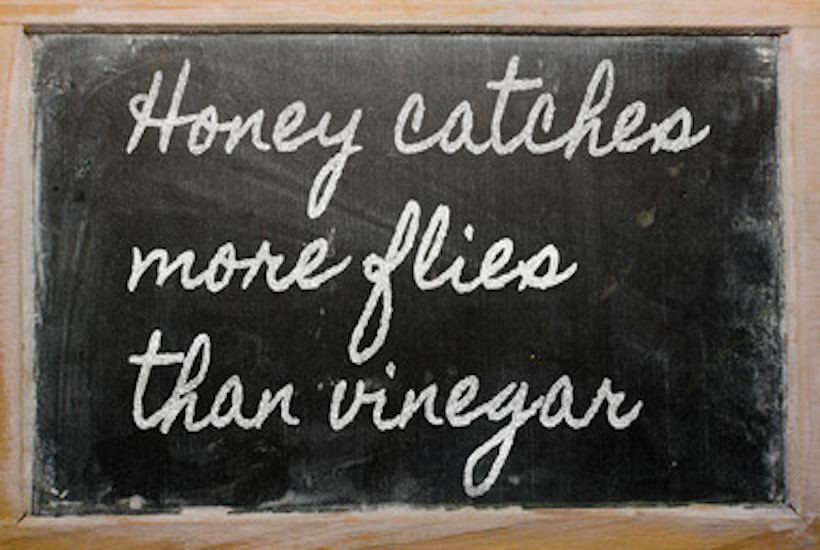

If we remembered that compassion for our neighbour is at the heart of Judeo-Christian values, we would be spending less time fighting a culture war and more time fighting for the dignity of all, no matter the cost to ourselves.

Chaneg Torres is the Secretary of the New South Wales Young Liberals

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in