It is not as surprising at it sounds that two of the greatest collectors of modern art should have been merchants from 19th-century Moscow. If Russia managed to contrive a semblance of western civilisation in St Petersburg, it was by virtue of being directly under the steely Tsarist eye. Moscow on the other hand, half lost in the shadows of barbarism, was more wacky and roguish. It liked to think it was home to the true Russian spirit, which artistically meant gaudy folk art, icons, sad music and weird architecture. However the tiny rich class were desperate for the oxygen of enlightened humanist society which they found, like their St Petersburg compatriots, in Paris (it must always be remembered that Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes could never perform in Russia).

Ivan Morozov, a textile manufacturer, and Sergei Shchukin, who made nothing but was a textile entrepreneur, were among them. They both bought in Paris and shipped back to Moscow a staggering number of masterpieces by Monet, Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and others, when the Modern Movement was still derided even in France. Only Leo and Gertrude Stein were quicker off the mark. Morozov kept his collection private; Shchukin however opened his every Sunday. I think it unlikely he would have been able to do this in St Petersburg; but even in Moscow he trembled sometimes at the scandal he might be causing. Ilya Repin’s wife, who should have known better but was envious and anti-western, wrote: ‘I wanted to get out of that house as quickly as I could.’

The Communists nationalised both collections. Stalin locked them away as degenerate. Why this book’s subtitle refers to ‘lost masterpieces’ I don’t know. The works, today shared between galleries in Moscow and St Petersburg, are among the glories of the Russian tourist trail. It is Morozov and Shchukin who were lost. Stalin didn’t just bury the pictures, he also did his best to erase from record the very existence of the two collectors. This book concentrates on Shchukin, whose collection was more plentiful and in certain respects more daring. He didn’t just buy, he commissioned, notably from Matisse whom he single-handedly saved from penury.

Something of the lurid primitivism in Muscovite culture chimed with the Gauguin of Tahiti and the Picasso of African masks; and when Matisse finally went to Russia, at Shchukin’s invitation, the one thing the artist raved about were Russian flat-field icons. But official Moscow wasn’t easily won over; and time-honoured charges were thrown at Shchukin, of ‘corrupting Russia and Russian youth’. Yet anyone less corrupt than the wonderful man who emerges from these pages can hardly be imagined: his deals were generous, his manners impeccable, his kindness and courage exceptional. There is a photograph of him taken in the 1890s. What a handsome face, strength and sensitivity in harmony, with steady eyes and a hint of Tartar in their shape. The lower part is hidden by facial hair, but the sensuality of the mouth is telling. Some years before the first world war, many in Moscow at last began to say that the contemplation of his pictures could generate mystical experiences.

The Collector is a resumé of three Russian studies of Shchukin by Natalya Semenova, who salvaged what she could from the mutilations of Communist censors. André Delocque is Shchukin’s grandson and he has been responsible for the adaptation. And the text has been translated. The book therefore is sometimes jerky and stilted, but the story it tells is magnificent. The heroic relationship between Shchukin and Matisse especially is a revelation in its tender detail: first quizzical meetings, hiatus, first serious purchases, bold commissions, Shchukin getting cold feet, Matisse heartbroken, Shchukin relenting. The poignant aftermath: Shchukin escaping with his family from the Red Terror, exiled in Nice and Paris, but ashamed to renew the relationship now that he was no longer able to buy from the Master.

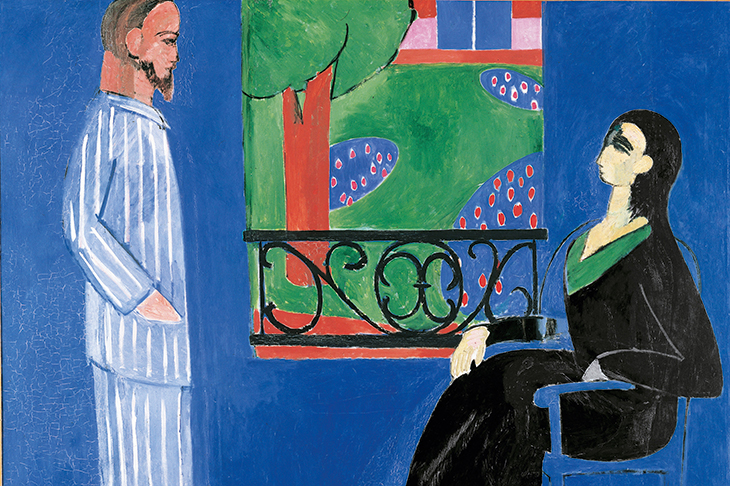

Shchukin displayed his collection in his home, the Trubetskoy Palace. Eerie photographs show the palace’s interiors plastered in a grotesque version of the French Second Empire, with canvases massed on the walls, including 38 by Matisse and 50 by Picasso. Shchukin loved the hothouse atmosphere thus created, an escape from many personal tragedies he experienced even before 1917. But the pictures were crushed. When Matisse saw his own there, he was outraged that they were behind glass. When I saw the ones in St Petersburg, they were up on a top floor of the Winter Palace, a plain setting, but still awkward.

In 2014 modern art was moved out of the Winter Palace and into a new space in the general staff building christened the Shchukin-Morozov Gallery. It is nice to know that today’s Russia, still brutally anti-humanist (President Putin has decreed that Tchaikovsky was not homosexual!), can get something right.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in