This new book, from the NYRB’s publishing arm, is in a non-fiction genre I love: short entries dedicated to an integrating purpose; approaching a subject via concentrated, separated stabs rather than extended unfolding text. In philosophy this is called the aphoristic technique. In wider literature, it can range from the concise notebook to prose poetry.

It is a genre whose masterpiece in English is Cyril Connolly’s The Unquiet Grave, but it is more often found in continental literature; and the French especially have made it their own, where its progenitor is usually said to be Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris, described as prose poems and published in 1869 after the author’s death. Baudelaire, however, is preceded by Gérard de Nerval, whose urban observations, collected in Les Nuits d’octobre (1852), are perhaps even more luminous.

It is a form which no American has pulled off. Americans have been much more effective at the diary: The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem is an enormous pleasure. Or reportage: Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, for example, also published posthumously. The caveat here would be that Hemingway in his notes reminds posterity that the contents are fiction — by which he means that his reportage has taken considerable liberties with actualité.

When Americans do attempt the genre, the result has been a peculiar mixture of the portentous and the trite — as in the works of Charles Simic, for example. And here is Henri Cole on blue hydrangeas:

This week, pondering the flowers — with their complex shadings of blue — in all the flower shops of Paris, I was reminded of how short life is but also of how tough and durable humans are.

Not good enough. The form demands greater penetration and originality.

Its appeal lies in its possibilities for experimentation and surface variety. Max Jacob’s astonishing Le Cornet à dés (1923) was the great leap forward here. Cyril Connolly made considerable use of quotations. The prewar surrealists introduced photographs, blotchily printed within the text, something lately repopularised by W.G. Sebald. Cole avails himself of both quotations and blotchy photographs. The thing about quotations is you must make sure your own contributions are not upstaged by them — Cole’s problem. As for photographs, don’t use them as padding. So despite appearances, this is a difficult form. Its apparent generosity is a trap. It’s not a matter of anything will do.

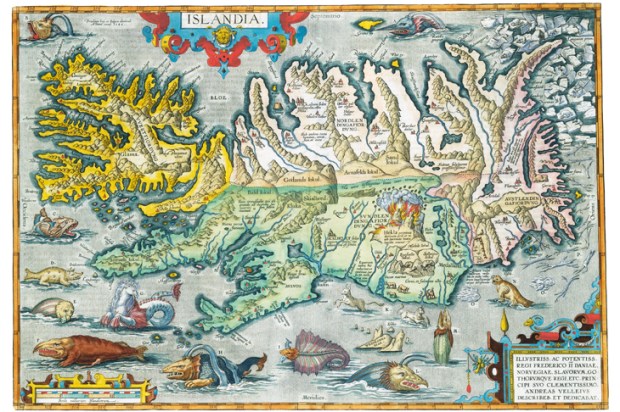

In the case of Orphic Paris, I was discouraged early. On page 13, Cole writes: ‘When I am in a foreign country, I am most at home near the shelf of books in English.’ He is telling us that he is not a traveller, not an adventurer. But he also tells us he is a poet; indeed, it is his main thing, to tell us he is a poet. So — a poet who dislikes adventure?

Also grating are his frequent lapses into ‘info’ in a work which should exist beyond that: ‘Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, a hill on the Left Bank of the Seine in the fifth arrondissement’; ‘I crossed the Seine into Les Halles (once the central market, or “belly” of Paris)’; ‘the taciturn English author Graham Greene’; ‘Pindar, the ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes’. It’s as though he’s addressing a public meeting, not writing intimate reflections. The last is the exact opening of Pindar’s Wikipedia entry.

One becomes increasingly aware that the book has no centripetal force. Nor centrifugal force. I was trying to establish its rationale, something which would enable me to engage with it more positively (I prefer not to write negative reviews). Could it be Da-Da-ist? But there’s nothing comedic or absurd here. Or random? Warmer. Randomist? No, no, that would imply ‘anarchist’, and Cole is not a violent man. In his frisson-free pages we are aware of a gentle soul on the mooch-about: listlessness searching for life.

When I came to the acknowledgements, it all fell into place: ‘The essays that comprise Orphic Paris originally appeared in the New Yorker’s Page-Turner.’ In other words, these are magazine fillers. Nothing wrong with that in itself. Those Baudelaire and Nerval books began as filler journalism too. But they didn’t stay that way. As for calling his entries ‘essays’, that’s naughty; and finding Harold Bloom comparing the book to Valéry — and others wildly over-puffing — produces a curious sinking of the spirits.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in