I’m back in New York and digesting the five glorious days spent in Normandy. What was the fighting all about, you may ask: was it about freedom, equality, cultural diversity, man’s dignity — all liberal catchphrases these days? Liberty and freedom are also big words nowadays, but all I see are massive central governments with arbitrary powers à la Brussels and Washington DC. Normandy promised us a lot but, as far as I’m concerned, delivered little. If freedom of speech was non-existent in Germany in 1940, political correctness makes it just as rare in London and New York in 2018.

Our stifling culture of PC makes the sacrifices of those young men who fell in Normandy seem, well, not in vain exactly, but hardly worth it. The material and spiritual degradation of the post-modern West — the porn, the violence and the greed — are not worth the life of a single Green Jacket, G.I. or Panzergrenadier. Call me a cynic if you like, but after visiting the graves of young Americans, British, Canadian and German soldiers, grief was replaced by rage at how we’ve squandered our precious victory. We are now all prisoners of a stifling cultural uniformity that punishes those who trespass as quickly and as mercilessly as any Gestapo visit ever did. Qualities such as virtue and civility are seen as irrational and harmful, and PC humbug reigns supreme.

I’ve already mentioned our Führer James, the king of LNGs Peter, and mein Kamerad Tassilo; the rest of the party were John Moore, a very successful businessman, Matthew Westerman, of the Imperial War Museum, Martin Houston, an oil and gas tycoon, Robinson West, a Washington insider, and Tom Harley, an Aussie international fixer on his way to Saudi Arabia, whom I instructed to ‘tell that fat towelhead MBS to stop murdering Yemeni children through starvation’, and who answered:‘I will make sure to use just such words for the maximum of effect.’ All nine of us are history buffs and over those five dayswe sure learned history down to the smallest detail.

Operation Cobra, launched by the Americans at the end of July 1944, created the decisive breach in the German lines: 1,500 B-17s and B-24s churned up the landscape with saturation bombing, and fighters with napalm joined in the cataclysm. Panzer Lehr was literally pulverised, 45-ton Panzers sent flying through the air as if they were toys. General Fritz Bayerlein answered orders from headquarters not to retreat with the following: ‘None of my men will retreat a single inch as they are all dead.’ Still the Germans held out in pockets set up on the Coutances–Saint Lô road. The Normandy hedges, tall and thick, helped the defenders set up and move, set up and move. ‘Better than concrete,’ said a grenadier.

Now Patton’s time had finally come. He landed in Normandy, told someone who warned him about snipers to ‘get lost’, took command of the 3rd Army and launched into the fray. One hundred thousand men followed. The Germans could only look at the thousands of men and wonder what if. At the start of the Normandy campaign, the Germans had 2,400 tanks; after 77 days of fighting they had… 24. You do the maths.

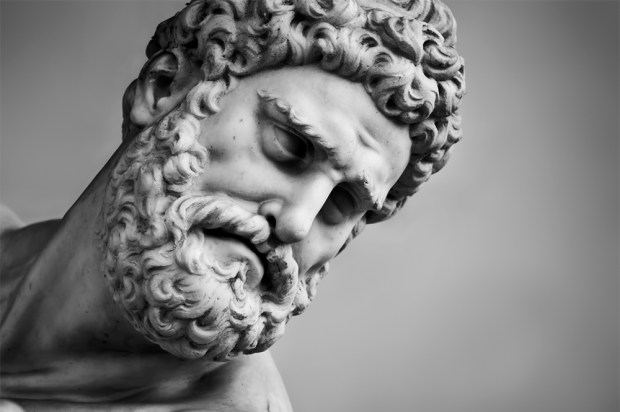

When the weather closed up, the Wehrmacht counterattacked and breached Allied lines time and again. When the sun shone, the Wehrmacht were kaput. Goering, back in Berlin, was into morphine, incidentally. What moved me the most was reading the ages of those fallen soldiers on all sides. I pick two out of 11,000 at the German cemetery at Marigny: Grenadier Christian Herrmann,17 years old, buried in the same grave alongside Sven Wieckmann, 18. Dark stone crosses for the Germans, slabs for the British and white crosses for the Americans in the magnificent, lined-with-evergreen-oaks resting place, the opening words of the ‘Battle hymn ofthe Republic’ carved on the bottom of the statue of a naked warrior guarding the dead.

By 11 August, Kluge’s counterattack is over as Typhoons flying in pairs pick off the remaining panzers. The Poles are massing in the Falaise Pocket sweeping up Germans who are now finally surrendering en masse. Our group stood in the corridor of death, as it is known, on the banks of the River Dives, imagining the panzers scrambling to break out of the pocket while taking constant fire from around and above. Everything’s ripped up and slashed open. Our final view is that of the bronze statue of General Maczek, the Polish hero who lived to be 102, and who sealed up the Falaise in the final battle after 77 days.

There were 500,000 casualties, 200,000 dead; what price Normandy? There were 2,600 dead per day, more, relatively speaking, than at the Somme. Dead horses everywhere, dead men and destruction. The sounds of battle are: mortar fire, slow; artillery shells, faster; heavy artillery, much faster. Earth-shattering detonation means there is just time to press one’s face to the ground and pray it stops, before the next chilling howl and more destruction. That’s war, not Hollywood bullshit. All those beautiful thoughts about dying for a cause quickly disappear. Aerial bombing drives men out of their minds, some tearing at their brains before falling dead.

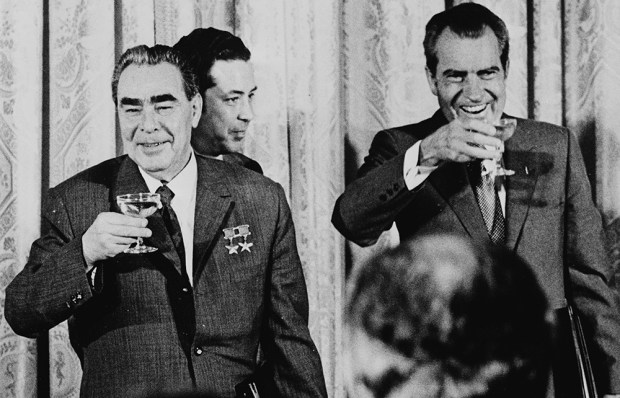

Heroes such as George W. Bush, Dick ‘five deferments’ Cheney, Bill Clinton, Mohammad Bin Salman and others of their ilk send young men to fight. I want to revert to the good old days, when leaders led from the front. You know the type — Achilles, Leonidas, Alexander, Miltiades, Ney. But I’m wasting my time. Shoot anyone over 30 who wants war.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in