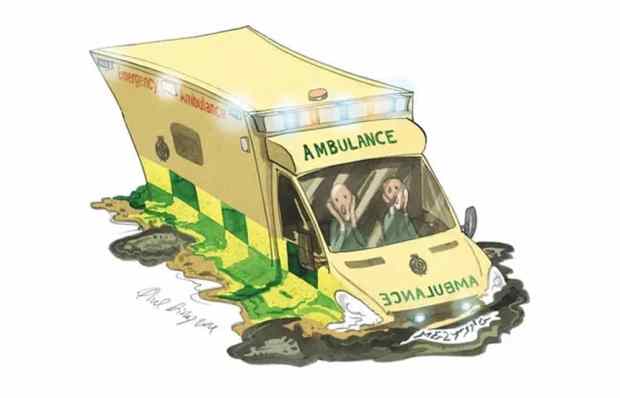

Gordon Brown, echoing Aneurin Bevan, says that the greatest gift that the NHS brings to people is ‘serenity’. He is surely right that this is what it brought 70 years ago — for the simple, important reason that people would no longer need to say of treatment, ‘I just can’t afford it’. But comparable ‘serenity’ is provided, in different ways, in, for example, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia. Defenders of today’s NHS have to explain not why it is more serene than pre-1948, but whether it matches the current arrangements of comparable countries. ‘Serenity’ is not the word one would apply to many British hospitals today. In these Notes last week, I mentioned the fear felt by the old. I did not mention one key reason for it. In a nationalised bureaucratic system, each patient is a cost. So the NHS is exactly the opposite of, say, a restaurant or a plumbing business, which lives by getting more customers. A cost is a burden, and so the system instinctively identifies those costs which are most burdensome and easiest to jettison. These are the old. Thus a feeling seeps through the machine that the old are to be fobbed off, sent home, neglected, drugged up or, in the worst cases (if stories like that of Gosport are indicative), put to death. However great the kindness of individual staff, the internal logic of the system itself is ruthlessly cold-hearted.

Media bias consists not so much in the exact words of a report, but in how it is framed. Ask of any story, ‘Who is being put in the dock here?’ and you will soon see where the bias lies. A current example is the horrible war in Yemen. The Saudi-led Coalition is always in the dock. Until an excellent short piece in Monday’s Times by Peter Welby (the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury and an interfaith worker in a region where that concept remains unfamiliar), I have read or heard nothing in Britain criticising the Islamist Houthi rebels and their Iranian backers. The frame of the recent story has been the terrible prospect of a Coalition conquest of Hodeidah. I do not doubt that the situation there is grim, but there will be two sides to the story and, if Mr Welby’s piece is right, the conquest will help end the fighting more quickly. Morally, it is not much fun having to choose between Saudi and Iran, but at least the former is the ally of the West. And there, perhaps, lies the explanation of the bias. Lazy media will have poor local sources, but strong links with NGOs whose vested and ideological interest lies in blaming arms-supplying western governments and their Gulf friends for Muslim ills. This gets close to fake news.

A new body called the Charity Tax Commission has been asked to look into the £3.7 billion tax reliefs given to charities. The Financial Ombudsman, Sir Nicholas Montagu, chairs the commission. He asks, ‘Are the right charities benefiting and should we start asking some awkward questions about whether there might be more to show for the money if we distinguished between charities?’ He invites the views of interested parties. Jonathan Ruffer, the rescuer of Auckland Castle, about whom I have written in these pages, has sent Sir Nicholas an interesting reply, based on his experience of giving away £200 million (95 per cent of his post-tax income) to charitable causes. He strongly challenges the idea of the ‘right’ charities. The principle of charity, Ruffer says, ‘is an absolute’. Of course, charities should be policed to check abuses, and there could be a redefinition, in law, of what a charitable activity is; but once one charity starts to be officially defined as ‘better’ than another, the whole principle of charity falls apart. The state takes over, prioritising, directing and distorting the charitable impulse: charities become, in effect, state agencies. This compromises the freestanding nature of charity and the free-will gift of the donor. For the same reason, the idea of HMRC getting ‘value’ for the money it foregoes in tax relief is ‘wrongly conceived, as well as being morally repugnant’. Charity is a vital social principle, but not a government one. Britain has for centuries been outstanding for ‘the depth and quantum of its charitable impulse’. Don’t interfere with it, says Ruffer.

We went to the perfect midsummer wedding of my wife’s god-daughter in Norfolk this weekend. The service was pure Book of Common Prayer, omitting only some of the longer prayers and the woman saying ‘obey’ and (I think) ‘serve’. The service states the theological nature of marriage (‘signifying unto us the mystical union that is betwixt Christ and His Church’), and then its purposes. These are 1) children, ‘to be brought up in the fear and nurture of the Lord’. 2) as ‘a remedy against sin, and to avoid fornication’. 3) for ‘the mutual society, help and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and in adversity’. I found myself checking off how many of these concepts would win the assent of most people in modern Britain. None of the religious stuff, of course. No duty (as opposed to desire) to have children, or to have them in wedlock, or to bring them up godly. No remedy for fornication, because it is thought to need no remedy. That leaves only ‘the mutual society, help and comfort’, and even this, nowadays, is freely available — at least in theory — just as much to couples unmarried as to married. So what’s left? Two lines of Larkin, from different poems, seem relevant. The first is about each person discovering in a church ‘A hunger in himself to be more serious’; the other, of course, is ‘What will survive of us is love’. The thought is inspired by a double grave (the Arundel Tomb in Chichester cathedral), but it is about marriage.

For about 50 years now, men have long ceded those ‘obey’ and ‘serve’ promises to women’s rights. So shouldn’t women reciprocate and release men from the promise (given most good-heartedly on Saturday), ‘with all my worldly goods I thee endow’?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in