The year 1971 was a busy one for Mary Whitehouse, self-appointed ‘Clean-up TV’ campaigner. Not only did she help establish the Nationwide Festival of Light, making religious inspired protests against the so-called permissive society, she also wrote an autobiography, Who Does She Think She Is?, published by New English Library. Thus her thoughts regarding the impending moral collapse of the nation were brought to the public by the same outfit responsible for a comprehensive range of sinew-stiffening pulp fiction delights such as The Degenerates by Sandra Shulman, Bikers at War by Jan Hudson and Gang Girls by Maisie Mosco.

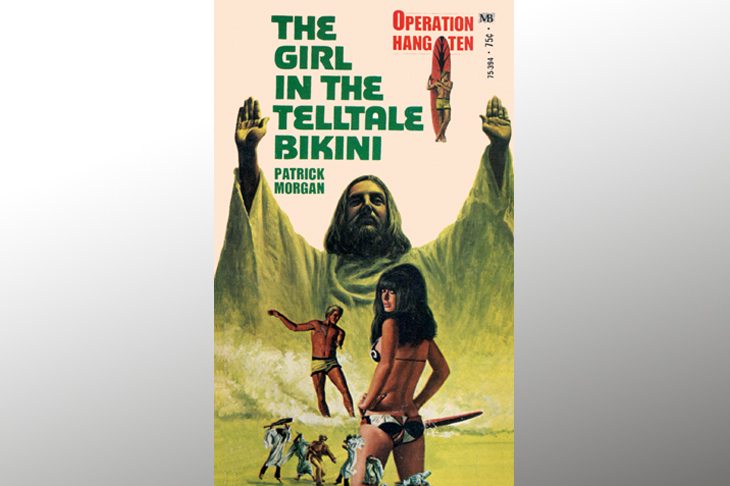

All of these and many more are featured in this heavily illustrated collection of essays, edited by Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette, who also wrote a significant proportion of the contents. The contributors, variously based in Australia, America, and the UK, examine the explosion of postwar cheaply produced paperbacks in those three countries, in fields such as juvenile delinquency, popular music, drug culture, biker gangs and the hippies’, mods’ andTeddy Boys’ youth cults.

Today, battered copies of Richard Allen’s million-selling exploitation titles Dragon Skins, Boot Boys, Knuckle Girls or Terrace Terrors, which survived being passed from hand to hand among schoolchildren in the early 1970s, are offered by respectable book dealers for considerable sums, and their contents analysed in learned institutions. At present, the cheapest copy on AbeBooks of Allen’s Skinhead (1970) is £37, whereas a paperback of the novel that won the Booker Prize that year can be had for £2.49.

Several of the essays here are written by university lecturers, yet there is no bibliography. This is disappointing, given the pioneering work done by earlier writers who were ploughing this furrow long before academia acknowledged its existence, for example Miriam Linna and Billy Miller in the 1980s, or Steve Holland with his book The Mushroom Jungle – A History of Postwar Paperback Publishing (1993). Some of the best work included here comes from people who have also been exploring the territory for decades, such as Stewart Home, who spent years on the trail of Richard Allen, and contributes a highly entertaining and informative interview with Laurence James, the man who signed Mary Whitehouse and many others to New English Library. Another such is Mike Stax, with a first-class piece on the British beat group and rock fiction of the 1960s, such as All Night Stand by Thom Keyes and Groupie by Jenny Fabian and Johnny Byrne.

The contributors’ appreciation of the novels under discussion is obvious, and there is much that is valuable here, but some have a tendency towards plain statements which do not hold water, making this book overall a resource of variable reliability. ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley & His Comets is said to have been ‘originally an obscure B-side’ until used in the film Blackboard Jungle (1955), yet it was reviewed and advertised multiple times as the clear A-side in Billboard magazine on its initial release in 1954.

It is similarly unwise to mock Ed Wood Jr for his ‘imperfect grasp of slang e.g. using “jazz” as a silly euphemism for “fuck”’, when this had been a legitimate usage for several decades, and was employed as such by Jim Thompson in his 1952 hard-boiled pulp masterpiece The Killer Inside Me. Elsewhere, Soho is referred to as a ‘suburb’ of London, and a short article about Ernest Ryman’s 1958 novel Teddy Boy concludes by stating outright that ‘history has left us no clues about the identity of Ernest Ryman’. Actually, he went to school in Edmonton, read English at Wadham College, Oxford, served in the Royal Navy in minesweepers alongside Ross McWhirter, and had a distinguished postwar academic career as a lecturer in Winchester and Brighton.

There are many fine cover illustrations from books not dealt with in the main text, but it is unclear whether the writers themselves have read them all, since they include a scan of The Immortal by Walter Ross in a picture section headed ‘Pulp Fiction Music Novels,’ despite the fact that it is actually the most famous fictionalised account of the film career of James Dean.

However, it was a real pleasure to read Andrew Nette’s sympathetic piece about Jane Gallion, self-described ‘fuckbook writer’, author of the novels Stoned and Biker, and editor for the Los Angeles pulp publishers Essex House and Brandon House. There, she co-authored numerous sex manuals such as Coito Ergo Sum, and occasionally attempted to sneak some humour into the company’s output despite the wishes of her boss — an incident she recalled in a lengthy autobiographical letter reproduced here. ‘Jane,’ he said grimly, ‘no satire. Ya can’t laugh and keep a hard-on.’

In the midst of it all even the authors sometimes made money, not least Mary Whitehouse, who, according to Laurence James of New English Library, would order by the thousand from the publisher at trade price, and ‘did very well out of it’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in