The events of this book take place where the world of the living and the world of the dead rub shoulders. Mama, 12-year-old Jojo’s grandmother, hears the voices — singing, talking, crying — of ghosts; Leoni, Jojo’s mother, sees her brother — ‘given, that he’s been dead 15 years now’ — sitting at the table, in the car, on the sofa between her and her friend, and every time she is high; and Richie, a 12-year-old boy whom Jojo’s grandfather, Pops, knew in prison, haunts Jojo, searching for a way ‘home’.

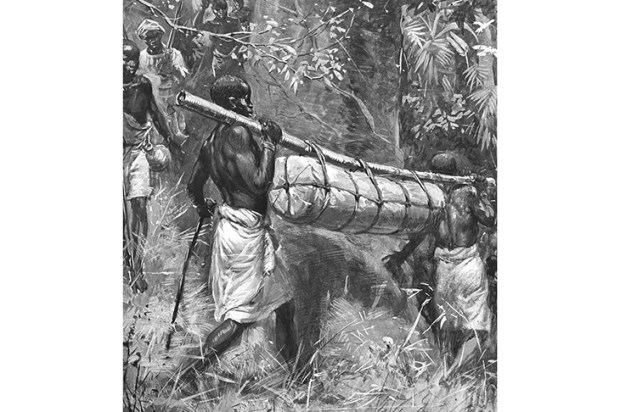

Sometimes despondent and aimless, at other times desperate and angry, the ghosts of almost exclusively black people are present everywhere — contorted into small spaces, crouched outside windows, ‘laying, curled into the roots of a great live oak, looking half dead and half asleep, and all ghost’ — each one ‘stuck’, due to the violence of his or her death.

These ghosts are the ‘unburied’ of a book that is otherwise grounded in realism. With them comes a reminder of the legacy of slavery, which hangs off the shoulders of each of the living characters like a heavy, physical thing dragged behind them, and influences how they are perceived by white people.

Jesmyn Ward is the first black woman to have won the National Book Award twice, first in 2011 for Salvage the Bones, a novel about an impoverished family in Mississippi in the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina, and second, this year, for Sing, Unburied, Sing. Also set in Mississippi, where Ward grew up, this new novel is equally real, uncompromising and devastating — and again has children at its centre, deprived of basic care or security.

It is a painful read. Small things tell us about the characters’ relationships: Jojo does not call Leoni ‘mother’; Kayla, Jojo’s three-year-old sister, refuses to be held by Leoni; Jojo refers to Michael, his white father, as ‘an animal’; Leoni is most at ease when on drugs, and least at ease when with her children.

When Jojo, Kayla, Leoni and Leoni’s friend leave to pick up Michael from prison, we understand Leoni’s incompetence as a mother and her violent temperament, Jojo’s dread and fear of leaving Pops, and the potential dangers of their journey. Yet this is also a disarmingly beautiful book — beautiful in every sense: in Ward’s full, complex characters, and in her prose, that can transform the ugliest moments (‘the latent violence coiled in Leoni’s arm, running from her shoulder down to her elbow and to her fist’).

Ward has achieved something extraordinary with Sing, Unburied, Sing. The voices, relationships and histories of her characters feel wholly true; and like the ghosts that occupy the book’s pages, they come to haunt us. Long after the end, we continue to worry after them, love them in spite of their faults, and feel their pain.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in