Princess Margaret was everywhere on the bohemian scene of the 1960s and 1970s. She hung out with all the famous rock stars, actors and other arty types of the day. Marlon Brando was struck dumb; Picasso wanted to marry her. As Craig Brown puts it artfully: ‘Everyone seems to have met her at least once or twice, even those who did their best to avoid her.’ And so, having noticed her ubiquity in the indices of other books, the satirist has written a hugely entertaining sort-of-biography.

Why would anyone do their best to avoid the princess? Well, she had a Prince Philip-ish way with the rude put down. (On being presented with a dish of Coronation Chicken: ‘This looks like sick.’) Secondly, the drunker she got, the more she pulled rank, leading to many a nightmarish dinner. And there was not much else for her to do but get drunk.

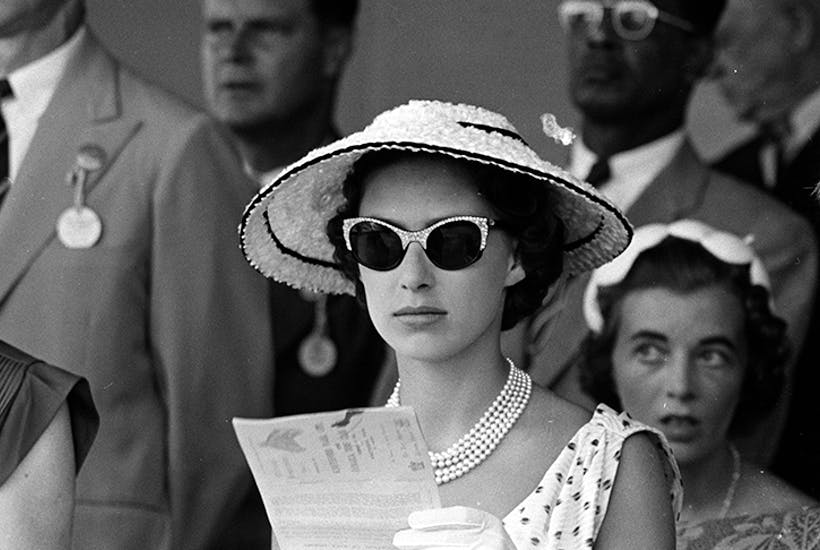

This is a darkly glamorous tale, after all, of a ‘punishing schedule of drinking and smoking’, punctuated by notorious love affairs. The first, with Group Captain Peter Townsend, is genuinely sad: first he is shunted off to Belgium by the establishment so they can’t see each other, and then she eventually renounces him rather than be forced to give up her title and go into exile abroad. The second, with the photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, later to become Lord Snowdon — immortalised here as ‘Tony Snapshot’, the bitchy name bestowed on him early on by the Earl of Leicester — ends in mutual contempt.

The book is brilliantly written, with a wonderful sardonic edge but also a thoughtful, at times even moving tone. Brown’s aleatory structure, hopping back and forth through time to present tableaux and anecdotes from the life, is a triumph, and renders the book probably the least boring royal biography it is possible to imagine reading. After all, as Brown, a connoisseur of the awful genre, points out: of all the arts, biography is ‘the least like life; and royal biography doubly so’.

Brown is a rightly celebrated satirist and parodist, but the sequences here that are pure counterfactual invention (an account of Margaret’s marriage with Picasso, for example) are somewhat less funny, perhaps because funny is all they are trying to be. More hilarious is his gimlet eye on, say, the stalkerish prose of her former servant’s memoir (‘my beautiful princess’, etc); or his drive-by analysis of the Queen Mother’s ‘ruthless contentment’; or his smilingly patient evisceration of the then-poet laureate Andrew Motion’s doggerel marking the Princess’s death.

Indeed, Brown’s real contumely is reserved for the crowd that Margaret attracted: the lickspittle hangers-on, the snooty theatre directors, the social climbers, and all the cynics who used her as edgy entertainment. ‘The connoisseurs wanted to see her getting uppity; it was what she did best,’ Brown notes. Besides such ‘laughing sophisticates’, the Princess herself could even seem an ‘innocent’.

Margaret was dismissed by some contemporaries as just another empty-headed snob, but on this evidence she was actually that rare thing, a cultured royal. She could play the piano and sing well, it seems, if exhaustingly — she would often go on till the small hours, exploiting the convention that no one could retire to bed before Her Royal Highness. Her friend Gore Vidal thought her ‘far too intelligent for her station in life’, and her often dismissive remarks about plays she had been dragged to see to derive from a rigorous (if circumscribed) taste rather than mere philistinism. Plus, it’s not as if the culture couldn’t do with more people who say what they really think upon leaving the theatre.

The Princess’s admirable commitment to dramatic realism, moreover, clearly motivated the story recounted here of her appearance on The Archers, playing herself at a country fair. After one take, the producer asked: ‘Do you think you could sound as if you were enjoying yourself a little more?’ Splendidly, Margaret replied: ‘Well, I wouldn’t be, would I?’ Quite. I think she might, on the other hand, have enjoyed this book — though it has no index, which is rather a sorry sign of the times.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in