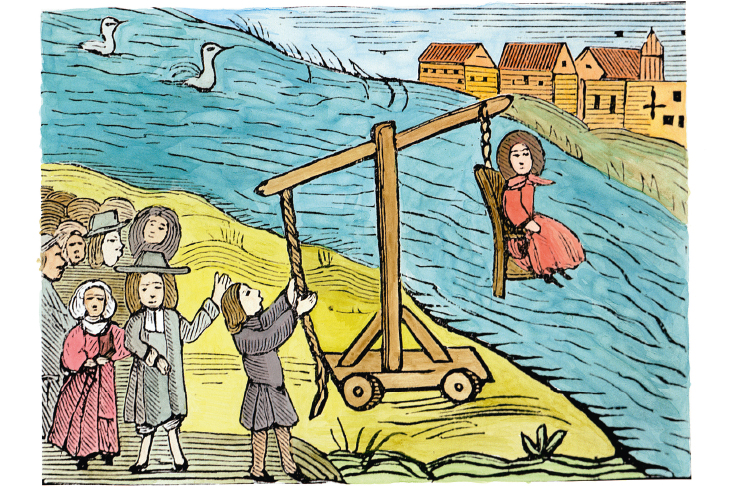

Until the mid-1960s many historians believed witchcraft was a pre-Christian pagan fertility ritual, witches worshipping the Horned God, whose consort was the Triple Goddess. The most notable advocate of this theory was the Egyptologist Margaret Murray. Then came revisionists led by Norman Cohn. Examination of witch trials suggested there had been no witchcraft: it was a ‘social construct’ of the Christian patriarchy persecuting innocent women, as it had innocent Jews indicted for the same satanic practices.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in