The rentrée politique in France next month promises to be the most exciting in decades as the dynamic superstar president Emmanuel Macron, aged 39¾, embarks on his mission to rescue France from its recent ignominy and restore it to glory. No matter that the polls are showing the shine may already be off this particular golden youth, and that a protest movement abruptly halted his wife, Brigitte, from having a formal First Lady role. President Macron marches on into the new political season, as full of confidence in his own abilities as he has always been.

Many have been the comparisons of Macron to the Sun King, Louis XIV, and even Jupiter, the Roman king of the gods, upon whom Macron models himself. In material ambition, however, Macron’s project sometimes seems closest to that of Louis–Napoléon Bonaparte, who was elected president aged 40, with an enormous mandate — and subsequently installed himself as Emperor Napoleon III in a putsch, before coming unstuck with Germany and ending his days in exile in England. In Surrey, where he is interred in an abbey at the end of the runway in Farnborough, Benedictine monks pray to this day for his eternal soul. His was an era in which great fortunes were made, modern Paris was created, Africa colonised, dissidents hounded, French culture flourished, and the administrative foundation was consolidated for what has to this day survived, after numerous iterations, as the immutable French state.

On such a Napoleonic scale, Macron’s teams of policy wonks have produced policies and plans for reform and change right across the inflated government and paralysed legacy economy, while carving out a new role for France as a global diplomatic, cultural, environmental and military colossus. It seems prima facie impossible, the detail intractable. Macron intends to simultaneously cut taxes and reduce the deficit. (Good luck with that.) He intends to restore competitiveness to France with an auto-da-fé of all that ails a nation performing dramatically below its potential, starting with the Jacobin code du travail, the breeze block-sized labour law compilation that poisons enterprise in a country where the customer is always wrong. He looks east to Germany, where he imagines France’s clapped-out army will make him equal partners with a nation whose economy is 50 per cent larger. A permanent state of emergency will, he hopes, keep a lid on dissent. And while he is at it, like Napoleon III, Macron intends to rebuild Paris, using the 2024 Olympics as a platform to relaunch a city that in many places is looking dangerously dilapidated.

The conventional wisdom is that he will fail, spectacularly. As the politicians re-assemble in Paris after abbreviated summer breaks, and the union bosses prepare their autumn of ‘social movement’, some polls show him already ten percentage points less admired than at the peak of his political honeymoon. Indeed, there are fault lines at the heart of the Macron project. Macron still seems confused as to whether La République en Marche, whose 360,000 ‘members’ are assiduously ignored, is a party or a cult. Not all is optimal in the imperial household. The received idea is that Macron will soon be shown up as an empty suit, no more capable of saving France than, for example, me.

But he may do something entirely unexpected — and succeed. Never mind the obviously deficient quality of his mandate. That he is not much loved in the country does not matter. Feel the width. He has total control of the National Assembly and it is almost entirely composed of placemen and placewomen who owe their entire political existence only to him. He has already secured from this compliant legislature the power to rewrite the employment code by decree. His government too owes its authority to the presidency, the political landscape behind ministers having been incinerated.

Maybe his official portraits by the Elysée photographer channel those of Kim Jong-un, but do not underestimate him. He is very clever and extremely cunning. He and his tiny kitchen cabinet are keeping a close eye on ministers. Big media is behind him, even if some of their group-thinking journalists are having second thoughts. The plutocrats, tired of broken promises, want their reforms. Many French people want change, and the forces aligned to oppose it have never been so weak.

And what is the alternative? The left and right have disintegrated. At least one of the big unions has signalled it is open to changes in the hitherto sacred text of the working code. While there’s bound to be some resuscitation of opposition, it is little threat for the immediate future. Who cares if schoolteachers go on strike? Who will even notice? They strike all the time. If the militant para-communist CGT union blocks motorways, it will be unsurprising if Macron sends the CRS riot police to unblock them. He might possibly get a huge cheer. True, some of his economic and fiscal reforms will be black magic: he will store up trouble for later, shifting costs on to communes. So the mayors won’t be happy; they never are. Tant pis.

This is not to say that Macron will achieve everything he has said he wants. Success is usually relative. The bar is set so low in France that any reforms at all will become major victories, or at least be claimed as such by Macron and confirmed to be so by the docile machinery of the dominant media, whose own subsidies, tax shelters and privileges do not seem to be on Macron’s hit list. The bankers, industry, parastatals and investors will not get everything they have been promised, but they’ll get a lot more than some imagine. And if the bloated state will not be comprehensively deflated, then if he can just stop it getting bigger that might be sufficient victory.

None of this must be confused with the notion that Macron is some kind of neoliberal, as imagined by the residual left. He is a statist and in that squishy way of the French hyper-elite, a socialist, or at least a nationalist. He didn’t hesitate when he was economy minister to protect Renault against a power play from Nissan. As President, in July, this neoliberal banker ordered the ‘temporary’ nationalisation of shipbuilder STX to keep it out of the hands of the Italians. He believes that the French state in its European condominium must always and forever be at the centre of national life and a major global actor. His role models include De Gaulle (and possibly Robespierre). Macron is not stupid; indeed he is brilliant. He worked for David Rothschild and knows that the capacity of the state to consume wealth is unlimited, and its capacity to produce it exactly the opposite. He knows that EDF is essentially bankrupt and that SNCF is a basket case and the economy has many more costly albatrosses just like them. His calculation is that by doing a bargain with business, the plutocrats will create jobs, wealth, tax receipts and political success for him. He’ll have reached a place never attained by his predecessors Holland and Sarkozy.

Though he may have a surprisingly successful autumn, Macron will never be adorable and if he has a looming political problem, it is this. At a minimum he needs respect, if not affection. He is very young in a country of gerontocracy. Macron remains more than odd and his marriage enigmatic. He is almost autistic, devoid of emotional intelligence.

He is arrogant, not charming. He survived his pre-election debate with Marine Le Pen only because she was awful. He has cold eyes and when Donald Trump visited for the big Bastille Day parade, there seemed to be a shared narcissism. But where Trump is a natural performer, and a salesman, Macron seems a little clumsy, aloof and geeky. He seems to do well with older women, not to overly emphasise the point. His failed demand for his wife, 25 years his senior, to be accorded status as First Lady was an ill-judged expenditure of political capital, but he has lots remaining.

Those of us who first underestimated Macron — I compared him at one point to Ed Miliband — were humiliated when he brushed aside our smart-alec scepticism and crushed all opposition, winning his énorme parliamentary majority, maintaining a hyperactive pace all summer, when his vanquished opponents were on holiday and when he put his legislators to work writing blank checks. His orchestrated mediatisation has been immodest. Taking over the Palace of Versailles to lecture first Putin, then his own legislature; being lowered from a helicopter onto a nuclear submarine; forcing out the chief of the armed forces; posing in a Top Gun outfit; cuddling with Bono and Rihanna; kindling a cult of Macronmania among New York Times writers; telling off Mrs May, and always on the phone, in German, with Mutti (Mrs Merkel).

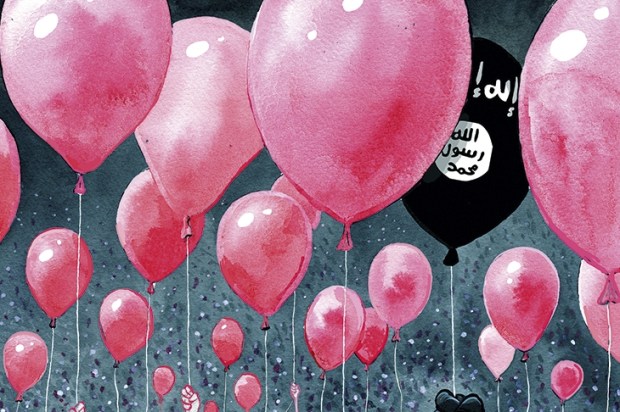

Macron is already making plans for his re-election in 2022, so perhaps judging him on what he can achieve now, before he turns 40 just before Christmas, is once again to underestimate the boy wonder and his long-term ambition. The final line of argument for Macron sceptics, that Macron’s promise to reform everything — the employment law, overheads on employment, too much tax, too much regulation, too much corruption, too much pollution, too much deficit, too many strikes, too many privileges, too many bureaucrats, crappy schools and universities, angry youth, taxi mafias, rampant terrorism, etc, etc, etc — cannot possibly survive a confrontation with the sclerosis that is modern France.

We shall shortly see, but it is perhaps wise to hedge one’s bets. What if he doesn’t fail? He might not be Napoleon III. What if he turns out to be France’s Thatcher?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in