After years of estrangement in a foreign land, what can immigrants expect to find on their return home? The remembered warmth and blazing beauty of Jamaica have remained with some British West Indians for over half a century of exile. Yet 100 changes will have occurred since they left. Long brooding over the loss of one’s homeland can exaggerate its charm and sweetness.

The first mass immigration to British shores occurred in the late 19th century, when Ashkenazim arrived by the thousand after escaping the pogroms in Tsarist Russia. Many changed their names and even their accents. The trappings of orthodoxy — beards, sidelocks — left them vulnerable to anti-Semitic abuse as they settled in cramped London streets north of Whitechapel Road.

Half a century later, ironically, the descendants of those Victorian-era refugees bitterly resented the presence of Jews from Hitlerite Germany. Not only were they seen as haughty, but they knew nothing of British culture. An estimated 55,000 German-speaking Jews nevertheless stayed on in Britain after the war. Their descendants are active now in the nation’s arts and media. Of Britain’s Jewish refugee dynasties, the Freuds are probably the most prolific. The fashion designer Bella, the novelist Esther, the publicist Matthew and the journalist Emma are all descended from Sigmund Freud, who escaped to London from Nazi Vienna in 1938.

The historian Keith Lowe, a renowned authority on the second world war, has written sympathetically on the plight of refugees from totalitarian Europe. His 2012 book, Savage Continent, offered a grimly absorbing account of postwar Europe and its lingering antagonisms. Its sequel, The Fear and the Freedom, concentrates on the psychological consequences of the 1939–45 conflict. Postwar propaganda and planning was effectively defined by a new age of the refugee. An estimated eight million Europeans had to be rehabilitated after the war. What to do with the tide of human misery?

My mother, who fled from the Soviet-overrun Baltic in the autumn of 1944, assimilated so deeply within British society that she could almost pass for an English woman. In London she read Country Life, drove my father’s British-manufacture Armstrong Siddeley saloon and said ‘What the dickens?’ quite a lot. Yet behind her veneer of Englishness was another story — one of flight and terror.

Based on the case histories of 25 individuals, one for each chapter, The Fear and the Freedom presents a vivid picture of postwar loss and rehabilitation. Sam King, a Jamaican who served in the RAF during the war, loved Britain and the British royal cult with its fripperies and rituals. Inevitably as a West Indian ‘room-seeker’, King experienced a degree of racism in postwar London. He was surprised to find himself categorised as ‘coloured’ (‘Room to Let: Regret No Koloured’); in Jamaica the term ‘coloured’ applied to people of mixed race, while in England it was one of the basic words of boarding-house culture and of polite vocabulary in general. Like the Jews who came to Britain after the overthrow of the Axis in 1945, King was often bewildered by the clubs, codes and conformities of the British. (The late George Weidenfeld, the Jewish émigré publisher, was taken aback when a London society hostess asked him: ‘I hear you come from Germany. Did you know the Goerings?’) But, as time went by, so Sam came to assimilate gratefully into British society.

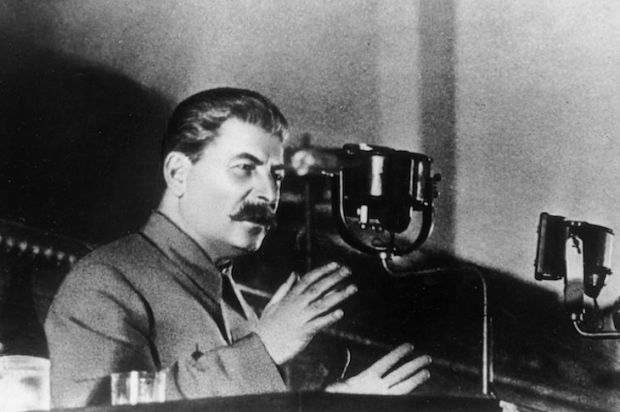

Refugees who found themselves adrift in the British zones of Germany after Hitler’s defeat were often riven by feelings of pain and foreboding. Allied aid workers listened sympathetically to their tales of loss and despair, but the local Germans, envious of K-rations and chocolate, often conspired to thwart the new alliances; so the war continued, pathetically, into peacetime. As Lowe points out, the war had not brought freedom to areas of Europe claimed by the Red Army, but substituted one form of tyranny for another: Hitler’s for Stalin’s. Poland was liberated from Hitler; but Poland was immediately afterwards occupied by Stalin. Neither of those words — ‘liberated’, ‘occupied’ — is inaccurate but in their juncture lies the sad fate of so many of the countries examined here by Lowe.

In his concluding chapter, Lowe considers Brexit calls for a curb on immigration. Make Britain great again — but no one seems to know what Britishness means any more. One thing seems certain. After the destruction of peoples and places during the war, British history can no longer be viewed merely as a saga of warring Saxons, Jutes, Angles and other Germanic tribes who settled in the 6th century in post-Roman Britannia. We speak of Great Britain, after all, a country greater than the sum of its parts, ‘diverse’ as they may be. Lowe’s book, superbly researched and written, is the beginning of wisdom in these things.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in