In this magnificent book, Thomas Morris provides us with a thoughtful, engaging and rigorous account of how cardiac surgeons through history have sought to undo the ravages wrought on the heart and its associated major blood vessels by abnormal genes, imperfect development, bacterial infections such as rheumatic fever, venereal diseases, unhealthy lifestyles and a host of other factors. He also offers an insight into the nature of scientific discovery, the mindsets of the characters driving it and the ever-present role of luck.

It was, indeed, a simple mistake made in 1947 by a young researcher called Arthur Voorhees that led to a chance observation which resulted in the development of the first artificial grafts to replace damaged blood vessels. Having in error placed a silk stitch into the one of the chambers of the heart, he noticed that it became covered with normal heart tissue. This emboldened him to sew a silk handkerchief into a tube and use it to replace a dog’s aorta. The makeshift artery functioned for just one hour, but when a year later he was sent a sample of a tough fabric used for the construction of parachutes, he was able to fashion a more robust prototype.

This pioneering work was picked up by the cardiac surgeon Michael DeBakey, who, using his wife’s sewing machine, stitched together the first polyester Dacron graft, with which he successfully replaced a patient’s diseased lower aorta.

Like the pioneering US air force test pilots of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, Morris’s pantheon of surgeons took tremendous risks; not with their lives but their consciences, livelihoods and reputations. Often faced with the vitriolic disapproval of their colleagues, and overshadowed by a catastrophic collection of their own failures, the discoverers of the armatorium of cardiovascular surgical techniques showed remarkable intransigence. Fortunately this bloodymindedness frequently paid off. The results are a triumph both of the human imagination, emotional resilience and supreme self-confidence.

Consistent with their reputation at the time of the first heart transplants as a glamorous club of medical elites, some of the giants of cardiac surgical history weren’t driven by altruism so much as by professional rivalry and gargantuan self-belief.

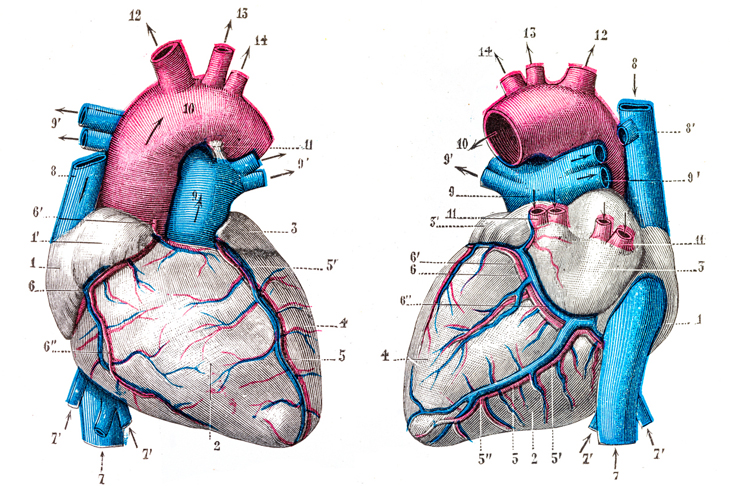

Morris offers a whirlwind tour of the history of cardiovascular surgery viewed through a series of breakthrough operations: from heart valve transplants and the repair of congenital heart defects, to the treatment of coronary heart disease with angioplasty, correction of arrhythmias with cardiac ablation, aortic dissection repair, insertion of pacemakers and the crowning pinnacle of their achievements, heart transplantation, using a machine that mimics the operation of the heart and lungs. It is peppered with vibrant anecdotes as well as biographical accounts of the individuals who made these important contributions.

We learn how the discovery was made that the heart is not just a simple pump, but rather a pumping device controlled by electrical activity; and of the remarkable finding that it may be brought back to life through the external application of electricity, a procedure known today as cardiac defibrillation. The latter resulted, in part, from the work of a certain Mr Squires, a resourceful amateur scientist who on

16 July 1774 appeared at the site where his three-year-old neighbour had fallen from a window onto the street. She having been pronounced dead, he took it upon himself to connect her chest to an electrostatic generator and found that he had managed to bring her back to life.

Seemingly obscure biographical details give pointers to the sources of some of these key discoveries. The surgeon Charles Bailey sold ladies’ underwear to fund his way through medical school, and was struck by the similarity between girdles and the mitral valves of the heart. Suspenders offered firm but flexible support to the stockings; much like the chordae tendineae, tough strings of tissue that anchor the valve leaflets to muscles on the inner wall of the heart. These insights led him to develop a new method for treating mitral stenosis, a condition in which this heart valve is thickened and obstructs the flow of blood.

It is unnerving that an organ as vital as the heart can fail in so many different ways; human hearts, although often functioning seamlessly for multiple decades, may all too easily be broken. This is certainly not a book for hypochondriacs. It reminds us, however, that we are not the perfect products of optimal creation.

But as a result of the historic work of the larger-than-life giants of cardiovascular surgery, the repertoire of surgical interventions they invented, and the discovery of drugs such as heparin that prevent blood from clotting, damaged hearts may now be routinely repaired.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in