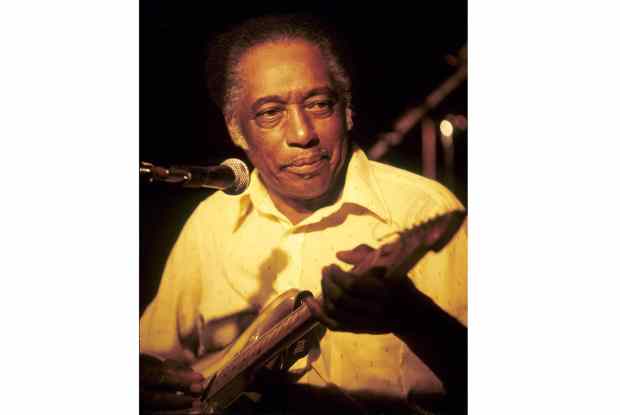

When techno first appeared amid the urban wasteland of mid-1980s Detroit, its futuristic sound palette was inspired by the whirring and clanking of the Motor City’s defunct assembly lines. Early techno was darker and more hypnotic than its close cousin house, but you could still dance to it. There was still soul in the machine. The music brought people together on dance floors in abandoned warehouses, offering hope amid decline. By the end of the decade, thanks to the crossover hits ‘Good Life’ and ‘Big Fun’, techno had taken root in the UK. Europe and the world would follow.

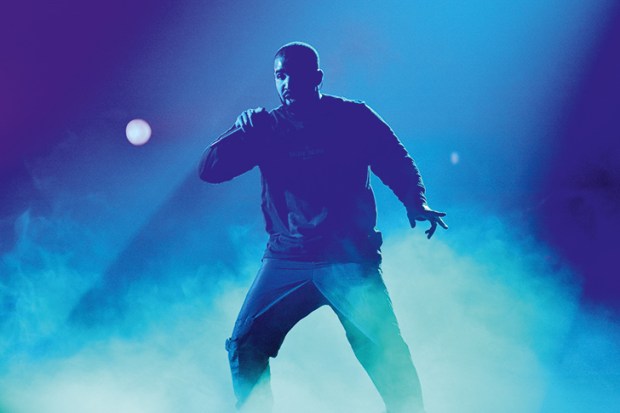

Jeff Mills belongs to the second wave of Detroit techno: the guys who took themselves too seriously and forgot that it was meant to be fun. As part of the Underground Resistance collective, he jealously guarded the ‘Detroit sound’, stripping the music back to its harshest, most industrial elements. A solo career followed, with records called things like AX-009ab and 4 Art/UFO. Mills completed his migration into high-culture pretension by moving to France, where last month he was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. His residency at the Barbican, From Here to There, was a fitting way to celebrate the achievement.

Life to Death and Back mostly consists of a contemporary dance film — rarely a phrase to inspire confidence — in which three dancers in slinky black outfits perform among the exhibits in the Egyptian wing of the Louvre. Pyramids and clouds flash portentously across the screen while Mills plays a live electronic ‘score’ on turntables and laptop at the back of the auditorium: all looped bleeps and chaotic, layered percussion that never settles into a regular beat. If it sounded like it was being made up on the spot, that’s probably because it was.

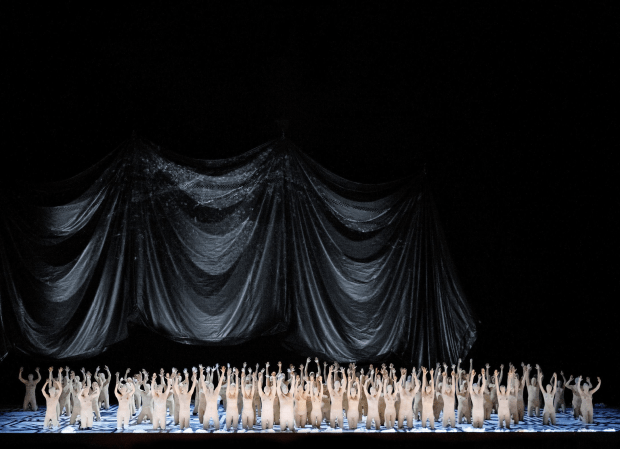

The dancers shuffle around the museum, occasionally undulating a limb or two or feigning awe at a sarcophagus. Later they appear — for real! — in the auditorium, holding glowing spheres which they continue to shuffle around onstage with, never threatening to do impressive or beautiful things with their bodies. Around the hour mark, they take off their clothes — some reward at least for those who haven’t left yet. I am told the whole thing had something to do with the reincarnation of pharaohs, but there was no way of knowing. At the end, they put down their big shiny balls and lie down, folding their arms over their chests, mummy-style, to the great relief of the audience.

For The Planets, an orchestral and electronic work inspired by Holst’s 1918 suite, Mills chucks the Greek mythology in favour of ‘actual data from Nasa’ — including the planets’ ‘rotation speed, their mass and density, the existence of water composites and other known facts’. Quite how this transpires to make Mercury sound like a sub-Rite of Spring, or Jupiter like Gershwin, we can only guess. Earth, reduced to menacing woodwind semitones, gets a bad rap. Perhaps it was the ‘water composites’.

The piece is described as a ‘cosmic tour or field-trip excursion to visit each planet’. Mills — by this logic the geography teacher of the electronic-music world — is a nothing-if-not-conscientious guide, supplementing the individual planets’ themes with electronic compositions to conjure up the distances between them. These vaguely cosmic sounds are interrupted by a sudden flurry of pizzicato strings between Mars and Jupiter — an asteroid belt! (Presumably.)

Still, Mills looks at home onstage with the Britten Sinfonia, dressed in a suit behind a bank of gizmos near the double basses over to the right. He is at pains to explain in the programme that this position ‘isn’t the focal point for the guest artist, but I realise that the return audio from my machine sometimes helps that section for synchronisation’. Ah, Mr Mills, ever magnanimous — even on a trip to Uranus.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in