One evening a few weeks ago I was on my way to the opening of an exhibition at the Venice Biennale when I stopped for a moment in a quiet campo off the main drag. An elderly priest was standing on the steps of the church of Santa Maria della Fava in the weak sunshine. On impulse I stepped inside and he followed.

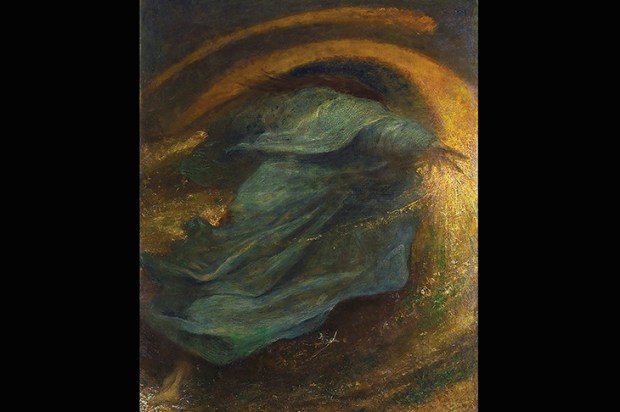

For a while I looked at Piazzetta’s altarpiece, ‘The Madonna with St Philip Neri’ (c.1725). Then — as if silently to indicate that I should have a look at this too — the priest switched on the light to illuminate Giambattista Tiepolo’s ‘Education of the Virgin’ (c.1732)on the opposite side of the nave. It was indeed worth contemplating.

The incident came to mind as I walked around the new exhibition, Canaletto & the Art of Venice, at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, precisely because pictures such as those two masterpieces of 18th-century Venetian painting — so full of power and feeling — are what you don’t see much of there. The Royal Collection is astonishingly rich in art from Venice of that period, but it’s a very specific selection: reflecting what Duke Ellington once described as ‘the tourist point of view’.

That’s all the more surprising since they were accumulated by a man who spent most of his long, long life living in Venice (in fact, in a palazzo not far from Santa Maria della Fava). George III bought them in 1762 as a job lot — with a work by the then almost unknown Vermeer — from Consul Joseph Smith (1675–1770), a talented, enterprising man who combined his diplomatic post with lucrative trading in such commodities as salami and pictures.

Smith was one of the major collectors of his day but also, effectively, an art dealer. He was a fixture on the Venetian scene for decades. Most visiting British notables encountered him — Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Horace Walpole, Joshua Reynolds, Robert Adam — and none seems to have liked him much. Walpole called Smith, perhaps snobbishly, ‘the Merchant of Venice’; James Adam complained about his insincere ‘flummery’ — ‘mere words, of course, which have no meaning except when he has some favour to ask’. The art historian Francis Haskell noted that ‘even across the centuries we sense something vaguely unpleasant about the man’.

Nonetheless — or possibly as a result —Smith was evidently a super salesman. From the late 1720s, he was the agent for a promising young painter of urban landscapes, Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697–1768), better known as Canaletto. Smith accumulated this artist’s work in amazing bulk, which is why the Royal Collection now has the world’s richest array of paintings, drawings and prints by Canaletto (Smith originally possessed many more).

In the largest room in the Queen’s Gallery are hung, along with much else, the series of 12 views of the Grand Canal that Canaletto painted for Smith in the 1720s and ’30s. These were on display in Smith’s own palazzo, to which he welcomed all those passing patrons. The pictures were also engraved — perhaps, Haskell suggested, as an ‘advertisement’. If so, it certainly worked. In the 1730s, Canaletto, and assistants, were turning out such Venetian views in bulk: 20 each for the Duke of Bedford and Sir Robert Hervey, 17 for the Earl of Carlisle.

The accusation against Smith is that he did what dealers — though not the best ones — are apt to do: encourage artists to turn out a saleable product. Even so, there is plenty to enjoy in Smith’s own Canalettos. Although the subjects are obvious, not to say touristy — 12 shots of the Grand Canal, six larger ones of Piazza San Marco — they take in some atmospheric and less familiar corners. It is fascinating, at least for the obsessive Venetophile, to see bits of the city that no longer exist — such as church and palazzi pulled down to build the station and the side of the Piazza San Marco demolished under Napoleon.

You also get hints here and there of another, more imaginative Canaletto who might have been. His views of Rome — especially ‘The Arch of Titus’ (1742), huge and looming, almost menacing — are a reminder that he was a contemporary of Piranesi. The little interiors of San Marco, shadowy and mysterious, are lovely too.

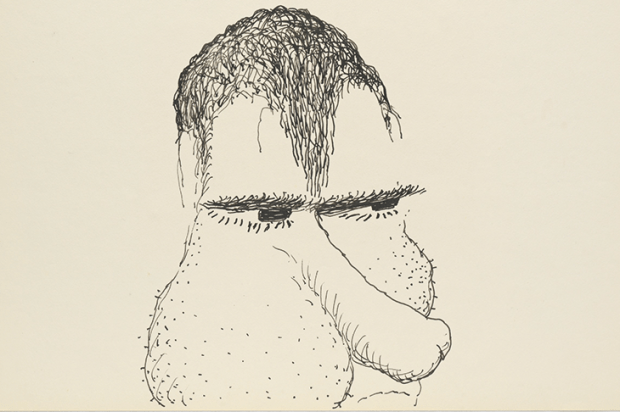

Smith, too, though he shrewdly understood his market, evidently had an eye. The Royal Collection has 36 marvellous chalk drawings by Piazzetta, almost certainly from his collection: quirky, almost earthy studies of ‘characters’. Those, however, are the exception. Canaletto apart, many of the works on show are on the soft and sugary side — by Zuccarelli, Rosalba Carriera, Pellegrini, the two Ricci, Marco and his uncle Sebastiano, country-house favourites whose works have the whiff of art for export. The full-strength stuff tended to stay at home, where it can still be found in undisturbed Venetian spots such as Santa Maria della Fava.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in