How did the cross, from being such a loathsome taboo that it could scarcely be mentioned, change into an image thought suitable viewing for all ages in public art galleries? There is no doubt about its early despicable reputation. A hundred years before the birth of Jesus, Cicero declared that ‘the very word cross should be far removed not only from the person of a Roman citizen but from his thoughts’.

It was the cross that gave rise to the word excruciating. It makes me feel rather queasy to envisage the slow death by suffocation of the crucified man, left without the strength to draw breath, so I was glad that Robin M. Jensen trotted fairly briskly through the forensic evidence, which includes a first-century heel bone with a nail through it.

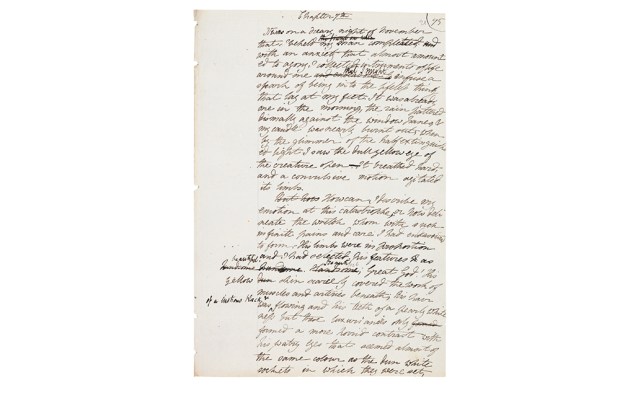

One might think that early depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus would be realistic, since the reality was still familiar. Only later would visual metaphors be developed. The opposite is the case. In the first centuries, it is true, his followers did not depict Christ on the cross, even though the crucifixion was put at the heart of their earliest writings.

The first surviving manuscript pictures of the crucifixion date from the sixth century and commonly, as in the Rabbula Gospels (named after their scribe, who wrote in Syriac), Jesus is shown dressed from shoulder to toe in a sleeveless purple robe with two vertical gold stripes. This was called in Latin the colobium. The British monarch is invested in a robe of that name after the coronation anointing. The coronation colobium is of plain linen; the purple, gold-striped colobium of pictorial crucifixes from the sixth to the tenth centuries is imperial and hieratic.

The cue for the idea of Christ on the cross being, not a tortured criminal, but a royal priestly figure, long predated the adoption by Constantine of the cross as an emblem that guaranteed victory in his march on Rome in 312. The two sources for Constantine’s vision were Lactantius, one of his advisers, who describes the sign seen in a dream as a Chi-Rho (XP, from the first Greek letters of the name of Christ), and Eusebius, his biographer, who says he saw a cross of light in the sky. What Constantine ordered to be made as his standard was a long, gilded spear bisected by a horizontal bar and topped with a golden wreath surrounding the overlapping X and P.

This might seem something very different from the crucifix, but Christians had always been aware that the author of the Gospel according to St John deliberately refers to the death of Christ on the cross as his ‘glorification’, a fulfilment of the Old Testament type in the book of Numbers of the brazen serpent lifted up on a standard (to save the Israelites in the desert from deadly snake-bites). ‘As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness,’ Jesus tells Nicodemus in St John’s Gospel, ‘even so must the Son of man be lifted up.’

This paradoxical notion of the cross as an instrument of execution and an emblem of victory was exploited by the Latin poet Venantius Fortunatus in his hymn ‘Vexilla Regis’. He wrote it for his friend and patron Queen Radegund of the Franks, who founded a monastery at Poitiers to house the gift, in about the year 569, of a relic of the cross from the Emperor Justin II. (He gave a similar relic to Pope John III, the reliquary for which, in the shape of a gemmed cross, is displayed in the Vatican. The king of the Visigoths and the queen of the Lombards soon got a slice too; it helped the barbarians feel less barbarian.) ‘The banners of the king go forth: / The mystery of the cross shine out, / By which the maker of our

flesh / In flesh upon a gibbet hung,’ goes this song, which is still sung all round the world in the days before Easter.

By Venantius’ time, the link was established, more by way of poetic exegesis than as a matter of history, between the tree of the cross and the tree of Eden by which, through disobedience, Adam and Eve fell, precipitating, in the fullness of time, the incarnation of God as man to save their offspring. Jesus was seen as the second Adam, so it was reckoned that Golgotha, meaning the ‘Place of the Skull’, where Jesus died, had been the site of Adam’s grave, and the skull (often depicted in scenes of the crucifixion) was Adam’s own. Moreover, the story went, the tree from which the cross was hewn had grown from a cutting of the Edenic tree.

This tale was picked up by the medieval bestseller the Golden Legend (later printed by Caxton), ensuring its universal propagation in the West. In all this, Robin M. Jensen, a professor at Notre Dame, is an authoritative, clear and enjoyable guide, especially to the unfamiliar world of late antiquity. Her use of pictures is particularly informative. She must be fairly tired of being confused with Robin E. Jensen, a professor at Utah and the author of Dirty Words: The Rhetoric of Public Sex Education. Perhaps they both are.

Professor Jensen, since she is factual and focused, does not mention it, but an analogue of the connection between the cross and the tree of knowledge is to be found in The Magician’s Nephew by C. S. Lewis. In his first book in the series, the author had (thanks to a sort of dream) put an anachronistic lamp-post in Narnia. By way of a posterior onomastic explanation, he attributes its presence in Lantern Waste to the wicked Empress Jadis having wrenched the crossbar off a lamp-post in Edwardian London and thrown it angrily at Aslan in Narnia, only for it to grow, in the fertile ground of the new world, into its parent post.

About 1,300 years before Lewis, an unknown author narrated the history of the cross in its own words. The Dream of the Rood, as it is known, mostly to unwilling undergraduates, was preserved by chance in a manuscript that ended up in Italy. ‘They mocked us both together,’ the cross recalls, ‘I was all wet with blood that poured out from this man’s side when he had given up the ghost.’

In a coincidence even more striking than the survival of The Dream of the Rood, some of its lines are carved in runes on the eighth-century sandstone cross, 18ft high, preserved at Ruthwell in Dumfriesshire. The Ruthwell Cross had been ‘taken down, demolished, and destroyed’ following an order of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1662, and put together again by the antiquarian-minded Rev. Henry Duncan in 1818. It interests me that scenes on its north side have a surprising Egyptian subject-matter, with captions in Latin, such as ‘Saints Paul and Antony breaking bread in the desert’, a reference to the successful search for the hermit Paul by St Antony, who memorably meets a centaur and a satyr on the way. The lives of these hermits were written by St Athanasius and St Jerome, top Christian intellectuals in the fourth century. It all seems a long way from rainy Ruthwell.

The demolition of the Ruthwell Cross had its parallels in Cheapside, where a stone cross was finally toppled by the Roundheads, or Geneva, where Calvin (in distinction from Luther, who was rather fond of contemplating the crucifix) denounced crosses and, even worse, relics of the cross. It was he who said ‘If we were to collect all these pieces of the True Cross, they would form a whole ship’s cargo’. I’m not sure that this quotable claim is strictly true. Cubic measure can easily produce a huge multiplicity of matchstick-sized pieces.

Certainly, when I came across a 15-inch relic of the cross (the largest now claimed) at the monastery of Santo Toribio de Liébana in the Cantabrian mountains, I had no hesitation, when it was proferred, in kissing it. The feel of the grain on the lips did suggest the thought of who had touched that wood before.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in