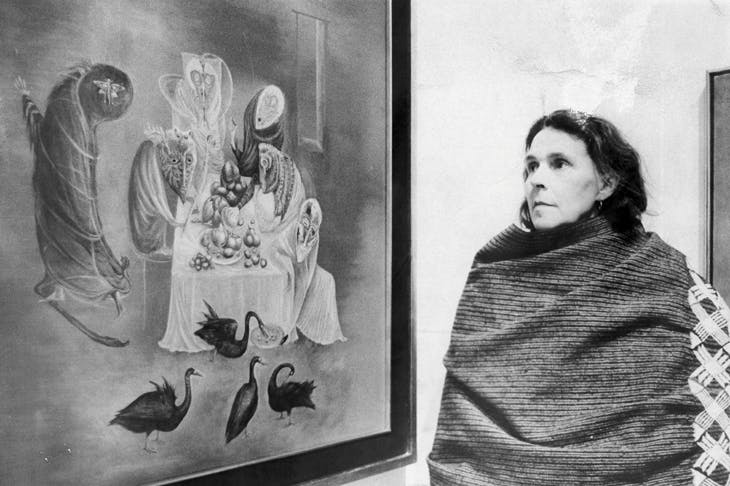

Leonora Carrington was strikingly beautiful with ‘the personality of a headstrong and hypersensitive horse’ (according to her friend and patron Edward James); and she fled from her family, renouncing a life of privilege and ease to pursue her calling as an artist. Joanna Moorhead deplores the fact that she is ‘not much more than a footnote in art history’.

But she has long been a legendary figure (among recent devotees, apparently, Madonna and Björk); in Mexico, where she lived and worked for most of her life, she is a national treasure; and for the feminist she is a heroine and her art ‘a modern woman’s codex’. She painted some marvellous pictures in her own, very personal brand of surrealism and wrote, in addition to fantastic, gruesome and often very funny stories, an account of her experience of madness, Down Under, which the Guardian considered one of the 1,000 books everyone should read.

In 2006 Moorhead, a journalist who writes mainly on family matters, discovered by chance that Leonora Carrington (1917–2011), an ancient, vaguely disreputable cousin of her father’s, was still alive and one of Mexico’s most celebrated artists. She set out to meet her in search of a good story; and the friendship that ensued over the last five years of the artist’s life, she tells us (more than once, changed the course of her own life forever. Moorhead was surprisingly unaware of the major exhibition of Carrington’s painting at the Serpentine in 1991 or of Susan L. Aberth’s 2004 monograph Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art (both of which challenge the idea that the artist was no more than a footnote in art history, and neither of which is mentioned in this book).

‘Stultifying’ or ‘suffocating’ are the words customarily used to describe the background against which Leonora so spectacularly rebelled and which she so ferociously ridiculed in her art. Her father was a wealthy textile magnate, her mother an Anglo-Irish Catholic. Her early childhood was spent in Crookhey Hall, a neo-gothic mansion in Lancashire, with three brothers, an Irish nanny and a French governess. But, as Marina Warner observes in an excellent afterword to The Debutante and Other Stories, it was an Edwardian childhood in which ‘the paddock on the one hand and the nursery on the other feature vividly as zones of thrill and transgression’ and the ‘rituals and privileges of her background… provided her with a heaped storehouse to raid’ for her stories and paintings. Rather than suffocation there seems to be a prevailing sense of freedom and lightness in the figures who drift about its gardens in Carrington’s 1947 painting ‘Crookhey Hall’.

A spell at a convent from which she was soon expelled (she told Marina Warner how she had wanted to be a nun or a saint: ‘I probably overdid it. I liked the idea of being able to levitate’) was followed by finishing schools in Florence and Paris before she was launched into society to find a husband. Moorhead devotes several pages to the dress in which Leonora was presented at court in 1935, but does not mention the charmingly surreal detail that debutantes were required to make their laboriously rehearsed curtsies to a cake (representing Queen Charlotte).

Eventually, her determination to become an artist prevailing against traditional parental warnings about starving in garrets (even Michelangelo’s father beat him for hanging around artists’ studios) was successful, and she was allowed to go to art school in London. Here, in 1937, she met the surrealist Max Ernst at the home of the celebrated modernist architect Ernö Goldfinger (whose ‘most enduring fame’, Moorhead rather curiously claims, ‘would be as the inspiration for James Bond’s most notorious adversary’). They became lovers pretty much on the spot, and Leonora ran away to live with Ernst in Paris and entered the circle of André Breton, Paul Eluard, Marcel Duchamp, Picasso and Dali.

Surrealism — which demanded the emancipation of writers and artists from all bourgeois constraints in both art and life — seems to have been made for Carrington. Her 1935 painting ‘Hyena in Hyde Park’ suggests a surrealist imagination already established, and from the outset, according to Susan Aberth, she was given ‘unparalleled opportunities to exhibit her paintings, publish her stories and participate in the movement’s activities’.

This does not, however, fit with Moorhead’s feminist agenda, and she speaks disparagingly of ‘the surrealist greats who once glanced in her direction and saw only a beautiful young woman whose presence might help them paint better’ and for whom Leonora was ‘the quintessential femme-enfant’ rather than an artist in her own right. It is a fault of this biography that the author retains such prejudices in the teeth of her own honest and scrupulously detailed evidence, which clearly contradicts them.

Max Ernst was interned as an enemy alien in 1939, and in 1940 Leonora left France for America via Madrid, where she had a spectacular mental breakdown and spent months in an asylum. It is difficult to disentangle this chaotic interlude. In her account, Carrington herself is aware of ‘drifting into fiction’. Madness was a state theoretically venerated by the surrealists and some of Leonora’s legendary surrealist pranks (such as slathering her feet with mustard in a smart restaurant or feeding her guests omelettes filled with their own hair) seem not dissimilar to the behaviour which in Madrid, raised ‘immediate suspicion as to my mental balance’ in ‘the ordinary bourgeois’.

Moorhead states, according to her own evidence quite unjustifiably, that ‘from being an inconvenience, Leonora had become an embarrassment’ to her parents. But after various adventures in which she evaded their ‘clutches’ and, spotting a handsome Mexican acquaintance across a crowded room, made a marriage of convenience to ease her passage to America, she arrived in New York in 1942. Here she re-connected briefly with Breton, Duchamp and Ernst (now married to Peggy Guggenheim) before settling in Mexico City.

In some ways the most intriguing part of Carrington’s life is the years she spent in the 1970s and 1980s travelling about the United States alone, with long periods in Chicago and New York, returning sometimes to Mexico to her second husband, the Hungarian photographer ‘Chiki’ Weisz and their two sons.

In her afterword to this first complete edition of Carrington’s stories Marina Warner describes how she visited the artist between 1987 and 1988 in the small basement room in New York where she painted and cooked ‘at a table between her bed and the kitchenette’ and ‘every week or so … would go to her gallery and deliver one of her dream paintings in return for a small stipend’. She was by then in her seventies,

small and thin, with very dark round eyes that still radiated the feral beauty of her youth, and a smoky voice filled with energy and humour. There was a quality in her of alert, warm curiosity about people and all phenomena.

Carrington’s ‘characteristic tone of voice is comic’, Warner observes, tracing its roots to English nursery classics: Lewis Carroll, Hilaire Belloc, Edward Lear and Harry Graham’s Ruthless Rhymes. The stories, many originally written in French or Spanish, are arranged chronologically. Some of the later ones become a little congested and more overtly satirical. Nothing, to my mind, quite approaches her first story, ‘The Debutante’ (and for the convent-educated there are some irresistible jokes in ‘As They Rode Along the Edge’) but her fantastic invention never fails.

Moorhead’s style is sometimes a little breathless (‘she and Max were hopelessly, totally and entirely in love’), but she provides much new and interesting detail, including the discovery that the house in Provence which the lovers shared in 1939 remains virtually untouched — their decorations intact, letters in drawers, books on shelves and Carrington’s golf clubs in the basement.

‘Romantic heroines, beautiful and terrible… come to life in women like Leonora Carrington,’ wrote Octavio Paz, one of her many lovers. Warner, ‘enthralled by her originality and captivated by her endearing magnetism’ found her ‘droll and warm-hearted and beautiful’, and she will undoubtedly continue to captivate. Can it be true that when she ran away to join Max Ernst and the surrealists she took her golf clubs with her?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in