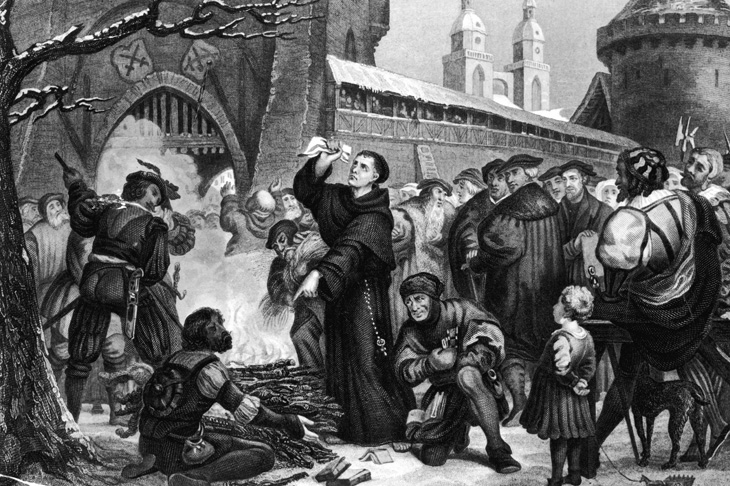

It’s 500 years since Martin Luther pinned his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, sparking what would come to be known as the Protestant Reformation. His superficial complaint was against the corrupt practice of indulgences, the Catholic Church teasing money out of the gullible and persuading them that they could buy their way into Heaven.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in