There have been many explanations for what happened in the Italian Renaissance. Some stress the revival of classical antiquity, others the rise of individualism. A pioneering exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Madonnas and Miracles: The Holy Home in Renaissance Italy, takes a different line. It’s all about the 15th- and 16th-century household — and the religious furnishings and fittings it contained.

To a 21st-century eye some of these are distinctly bizarre. Early on, there is a painting of the ‘Madonna and Child’ by a follower of Filippo Lippi — just the kind of thing one expects to find in an art gallery. Underneath it is a brightly painted wooden figure of the infant Christ, very similar to the one in the picture. But this was not so much a sculpture as a doll for a fervent adult. A mystic named Camilla Battista da Varano received visions while kissing, holding and nursing just such a replica baby Jesus ‘with great tenderness’.

Other items in the exhibition touchingly reveal the anxieties of their owners, such as a crude woodcut of the crucifixion with a prayer asking for protection from sudden earthquakes beneath (in that respect, life in central Italy hasn’t changed). In the category one could label ‘for the Renaissance home that has everything’ there is a set of dinner knives. Each has engraved on the blade a Latin grace and benediction plus musical notes. The idea was that before and after eating, everyone in the household could give thanks, singing from the score on their cutlery. Like so many ingenious gadgets, these never caught on.

Madonnas and Miracles makes the case that Renaissance Italy was a much more devout civilisation than has often been assumed. The nudity and bodily beauty of Botticelli’s ‘Venus’ or Michelangelo’s ‘David’ might suggest that this was an era of sensuality and secularism. But it was also a time when religion was taken very seriously, so much so that in the mid-16th century Europe fragmented and descended into savage warfare because of disagreement on points of theology.

Piety also permeated the average home, whether those living in it were super-rich financiers such as the Medici or the Renaissance equivalents of Mrs May’s just-about-managing class. The exhibition mixes up what we would normally think of as high art with much more downmarket objects. And it brings home how often even those works we now think of as masterpieces of art originally had a religious purpose.

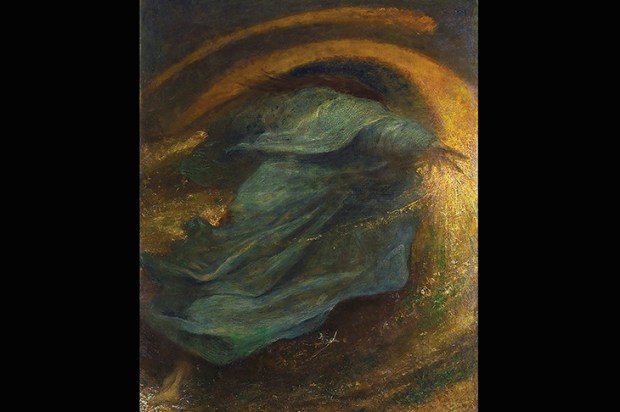

Certain areas of a tender, and very rare, drawing of ‘The Dead Christ’ (c. 1432–4) by Fra Angelico are softly blurred. It looks as if they have been touched and kissed by the owner (perhaps a member of the wealthy Strozzi family). So this wasn’t a study made by Fra Angelico as a preliminary to painting his ‘Descent from the Cross’. It was a reproduction of the central figure intended for someone to contemplate and venerate in private. Its purpose was not appreciation of the marvellous draughtsmanship; this was an aid to the spiritual imagination.

Sometimes, however, it’s hard to know how a picture appeared to a 16th-century viewer. Annibale Carracci’s ‘Mary Magdalene in a Landscape’ (c.1599) is both tearful and voluptuously bare-breasted, and to the modern gaze it seems mildly erotic. The justification, according to Federico Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan, was that depicting the Magdalene thus, as a young woman of ‘vibrant freshness’, emphasised her love of Christ all the more. Perhaps, though, even in the counter-reformation not everybody looked at the painting in quite such a virtuous way.

A lot of the exhibits in Madonnas and Miracles are aids to domestic devotion: rosaries, terracotta decorated with Biblical scenes, jewellery with pious inscriptions. There is a section devoted to the Jewish home, a reminder that Christians — though hugely in the majority — were not the only religious group in Titian’s Venice or Botticelli’s Florence. This, too, is full of devotional ornaments and accessories.

A spectacular display of ex-voto panels at the end of the display is an index of Renaissance anxieties — or looking at it another way, an anthology of contemporary accidents. In one a boy has given himself a nasty cut on the throat with a pair of shears, in another a diner is attacked by a bandit while still at the table.

In every case, supernatural aid is at hand: St Nicholas of Tolentino appears in the sky above to retrieve a victim who has tumbled into an enormous barrel of vino. The image marked a thanks-offering — ‘ex voto’ means ‘from a vow’. No doubt as the foaming vintage closed over her head, the unfortunate woman had implored the saint to save her from drowning.

This beautifully conceived and installed exhibition makes you think freshly about all manner of objects, from cheap and cheerful pieces of folk art such as those ex-voto panels to paintings of the highest quality. All of them were intended to affect the behaviour of the people who owned and used them. As the 15th-century architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti put it, ‘The images of things impress themselves in our minds.’ In other words, pictures are powerful. That’s still true.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in