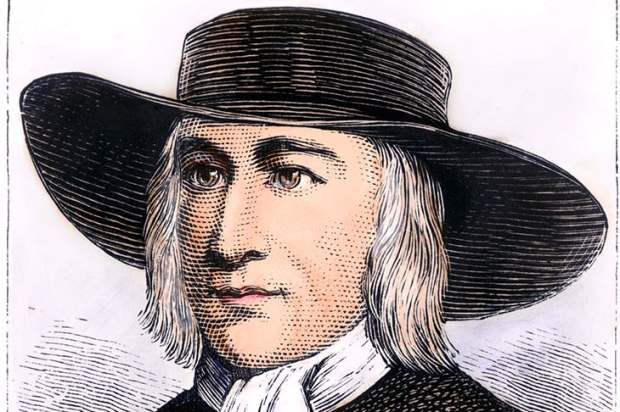

Kahlil Gibran was 40 years old, a short — he was just 5’3” — dapper man with doleful eyes and a Charlie Chaplin moustache, and in the first throes of the alcoholism that would result in his early death, when in 1923 he published The Prophet.

A collection of 26 prose-poems, written in quasi-Biblical language, the book takes the form of sermons by a fictional sage named Al Mustapha, on the big questions of life: family, friendship, love, work and death. These range from the profound to the banal. ‘Love gives naught but itself and takes naught but from itself. Love possesses not nor would it be possessed; For love is sufficient unto love.’ And who could argue with that? But then again. ‘And forget not that the earth delights to feel your bare feet and the winds long to play with your hair.’ A nice enough thought, but is it really true?

Since its publication, The Prophet has sold millions of copies around the world, in dozens of languages. It was particularly popular with hippies in the Sixties, and is a mainstay at weddings and funerals, taking its place alongside, at best, St Paul’s letter to the Corinthians and, at worst, Max Ehrmann’s ‘Desiderata’ as a sort of universal balm for the soul, its truths worn thin by repetition and its platitudes drowned in the syrup of the greetings card, tea-towel and fridge-magnet industries.

But oddly, for one of the world’s best-selling authors, little has been written about Kahlil Gibran — just two major biographies in the last 50 years, of which this is one.

Written by the son of Gibran’s cousin and his wife, Beyond Borders was originally published in 1974, and appears now in a considerably revised edition. Beautifully produced and illustrated with photographs and reproductions of Gibran’s drawings and paintings, it provides an exhaustive account of Gibran’s journey from a poverty-stricken childhood in Lebanon, through the bohemian and literary circles of Boston and New York, to international renown.

Gibran was born in 1883 to a Christian Maronite family in Bsharri, Mount Lebanon, in what was then Ottoman Syria. Growing up in an atmosphere of sectarian strife between Christians, Muslims and Druze, he was, by his own account, a solitary, thoughtful boy who seldom smiled, and who amused himself by drawing and writing stories and plays.

His father was a gambler and drinker whose job as a local tax-collector led to his arrest for embezzlement, obliging him to remain behind when in 1885 Gibran, his mother Kamila, his elder brother Peter and his two sisters migrated to America.

Penniless, they settled in the small Syrian community in the squalid slum of Boston’s South End, where Kamila supported the family by peddling goods from door to door, within a year earning enough to set up Peter in a dry-goods store, where the sisters, Sultana and Marianna, worked as salesgirls.

Gibran, for the first time in his life, was sent to school, at the same time attending a charitable ‘settlement house’, designed to instil culture into the children of impoverished families, and where his nascent talents as an artist led him to the door of Fred Holland Day. A photographer, publisher and aesthete, who enjoyed dressing in a fez and curled-toe slippers, Day seemed attracted equally to Gibran’s artistic talent and his ‘otherness’, photographing ‘the young sheik’ in a burnoose like an exotic specimen from another world. Day introduced the young boy to the works of Maeterlinck, the transcendentalists Emerson and Whitman, and the gay English mystical socialist Edward Carpenter.

Day seems to have been — to borrow a term favoured by Carpenter — Uranian in his enthusiasms, although this is not mentioned in the book, nor the fact that he liked to photograph his young subjects nude. But he was instrumental in setting Gibran on his path as an artist, commissioning illustrations for books of poetry and an edition of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and in 1904 holding an exhibition of Gibran’s drawings in his studio.

Gibran’s sensuous appearance and his air of wounded vulnerability made him particularly attractive to older women. The first was the poet Josephine Peabody, whom Gibran met when he was just 15 and she 23. ‘He writes Arabic poetry all night,’ she wrote, ‘and he draws (much better than William Blake) all day,’ declaring him to be ‘an angel from God’. Peabody and Gibran exchanged heartfelt letters — some of which are published here — which suggest a relationship of deep and mutual but chaste adoration.

Gibran took others’ estimation of him as a rarified combination of artistic genius and mystic at face value, and showed no inclination to earn a living from anything other than his art. When his brother died, Gibran briefly took over his dry goods store, but quickly dispensed with it. Following his mother’s death, he lived off his sister, Marianna. In short — and while this book is much too respectful to put it this way — he was a champion sponger, and he found his greatest benefactor in the shape of the education reformer Mary Haskell.

‘Khalil,’ she wrote, shortly after their first meeting, ‘is quietly and calmly usurping a place in my thoughts and consciousness and in my dreams.’ Ten years older than Gibran, Haskell shared his belief in a universality of spirit, and nurtured his aspirations ‘to give a GOOD expression to a beautiful IDEA or a high THOUGHT’. She would become the the most significant figure in his life.

In 1908 she paid for Gibran to spend a year in Paris studying painting, and despite being far from wealthy herself continued to support him financially thereafter.

‘You looked at money so wonderfully,’ he wrote in a letter to her:

You said money was impersonal, that it belongs to none of us, but it simply passes through our hands; a responsibility not a possession; and that our right relation to it is to put it to rightness.

A philosophy that clearly worked in Gibran’s favour.

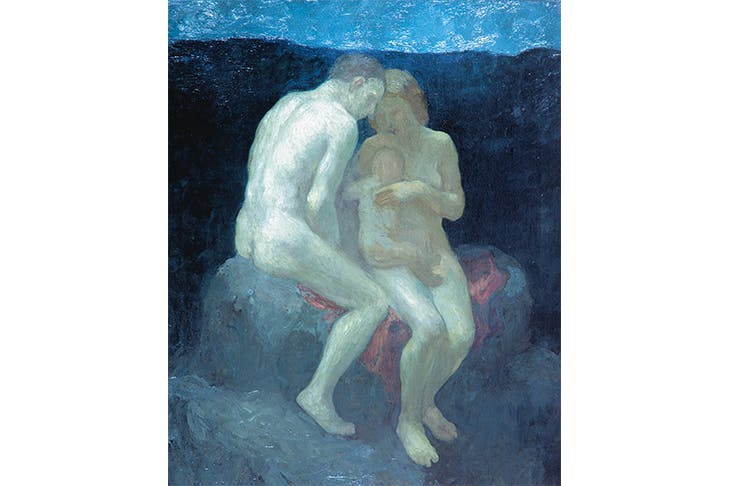

Haskell believed Gibran might be a reincarnation of Rossetti (who in turn, she believed, was a reincarnation of Blake). But Gibran cited as his main influence the French symbolist Eugène Carrière, with his ‘love of the manifestations of Nature’ and ‘the mysterious haze that hung over his paintings’ — which Gibran adopted himself, both in his ethereal, graphite drawings — spiritual allegories with titles such as ‘The Cream of Life’ and ‘The Souls of Men’ — and in his highly stylised paintings of centaurs, angels and entwined nude figures reaching upwards to a higher plane. Which is where Gibran and Haskell’s relationship appeared to rest.

At one point Gibran proposed marriage. Haskell turned him down on account of the difference in their ages, then changed her mind — and changed it again. But there is no suggestion their relationship was ever consummated. Other accounts of Gibran’s life have delved further into this, suggesting that Gibran spurned her offer to be his mistress, explaining that he was not ‘sexually minded’, while at the same time having other lovers. But the Gibrans’ book, sanitised and consistently deferential in tone, makes no mention of any of this.

Between the ages of 20 and 30, Gibran wrote primarily in Arabic — poems and stories which drew on myths and legends of his native Lebanon. As his reputation grew among the émigré Arab community, he became progressively more involved with the cause of Syrian Home Rule, agitating for an alliance between Christians and Muslims to overthrow Ottoman control. ‘Treat poetically with the Turkish government,’ he told Haskell. ‘You might as well sing the songs of Keats to… Standard Oil.’ But his principal theme remained one of religious reconciliation; as a Syrian newspaper put it, ‘Jesus is in half his soul and Muhammad in the other half.’

It was Haskell who encouraged him to broaden his readership by writing in English, helping him by correcting and improving his manuscripts — not least The Prophet. While Gibran described it as the culmination of his life’s work and experience — ‘all these 37 years have been the making of it’ — the book owed much to his conversations with Haskell, and her painstaking editing and revisions.

In 1926, three years after the publication of The Prophet, and in need of an emotional and physical comfort that Gibran was unable to offer, Haskell married an older man. Gibran apparently shrugged it off, although he continued to send his work for her appraisal. She edited and revised the manuscript for his book Jesus, The Son of Man while her husband was asleep.

Throughout his life Gibran had been plagued by what Haskell described as ‘an ongoing malaise’ — undefined, but which seems to have been as much existential as physical. He had also, as the authors put it, ‘always enjoyed a drink’ — notably arak, supplied by his sister Marianne. In 1925 an ill-fated real-estate venture with a friend, converting some old row houses into a business women’s club, exacerbated his worries (no prizes for guessing who paid off the debt) and he turned increasingly to alcohol ‘as medication’. He died in 1931 of cirrohsis of the liver.

By then The Prophet was comfortably on its way to its first million in sales, in the process fulfilling the view of Mary Haskell —somewhat prophetic herself — that the book would be

held as one of the treasures of English literature, and in our darkness and in our weakness we will open it to find ourselves again and the heaven and earth within ourselves.

She had not envisaged tea-towels.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in