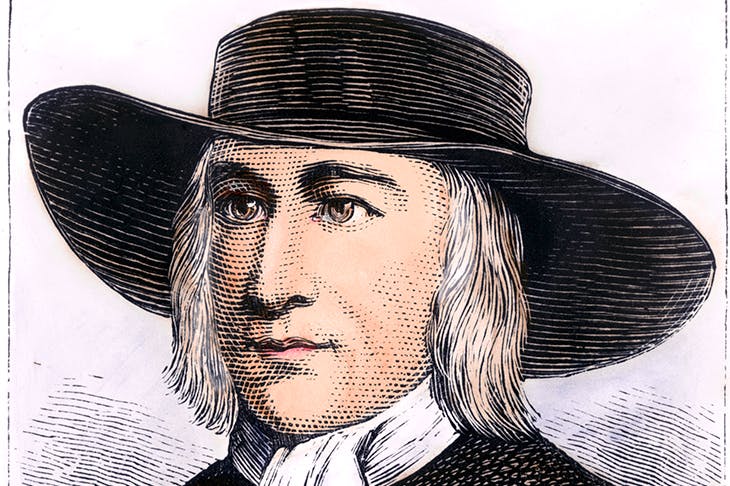

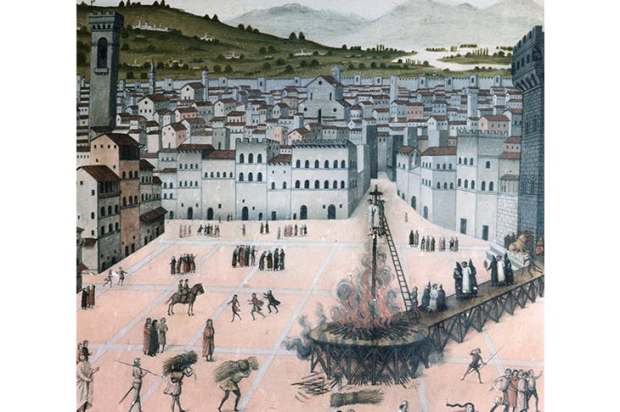

The Reformation is such a huge, sprawling historical subject that it makes sense, in this the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther producing his 95 Theses, to break it up into bite-size pieces in order to sample its distinctive local flavours. Eamon Duffy, emeritus professor of Christian history at Cambridge, takes England as his territory, and quickly deprecates the very word Reformation as an ‘unsatisfactory designation concealing a battery of value judgments’.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in