ACTU President Ged Kearney last year took to the stage at the International Labor Organisation conference to make an impassioned plea for domestic violence leave become a non-negotiable workplace entitlement right across the developed world.

Kearney isn’t just talk. The ACTU is currently running a test case before the Fair Work Commission calling for 10 days annual domestic violence leave to be mandated as a standard employment condition for all Australian workforces.

Domestic violence is, of course, a heartbreaking scourge no person thinks should be taken lightly. But ever since Rose Battie was made 2015 Australian of the Year how we talk about this most vexing of topics has become constrained by wide-eyed idealism and woolly-minded clichés.

Such dogmas include that domestic violence affects every corner of our socio-economic strata, lad culture or so-called ‘male bonding rituals’ condone and indeed encourage violence against women and finally that domestic violence is not sufficiently reviled by ‘Aussie culture.’ This has resulted is a climate of groupthink where any possible measure put forward under the banner of fighting domestic violence is lavished with uncritical praise.

But as with any major social ill, the truth about domestic violence is far more nuanced than the popular zeitgeist would have us believe. And when we’re talking about the kind of prickly topics like domestic violence that arouse our deepest sympathies and rawest sensitivities, the truth matters.

Despite a flurry of press conferences, gestures, pronouncements and no shortage of public funds, domestic violence has proven itself less than receptive government intervention. In the five years to 2014, rates of family abuse in some states including New South Wales increased while holding steady in most others. Nor should this shock anyone. Domestic violence is heavily linked with depression, substance abuse and other social ills like unemployment and, unsurprisingly, violence and criminality outside the family home. As Miranda Devine pointed out last year, the rate of domestic violence in the New South Wales town of Bourke is more than 60 times higher than the northern suburbs of Sydney. Financial strain, unemployment, alcohol or drug dependency issues, and perhaps most controversially, lower-socio economic status are all strong correlates of violence against women.

This is a rot unlikely to be uprooted by the Greens’ call for gender-neutral children’s toys or the Prime Minister reciting that we need to make violence against women ‘un-Australian.’

So how optimistic should we be that Ged’s suggestion of co-opting our industrial relations system into the mix will do the trick?

For a start, Australian workers already enjoy among the most generous leave entitlements in the developed world. As a starting point, a part -time retail employee working 20 hours a week can expect 80 hours or roughly four weeks minimum paid leave annually. This is supplemented by a laundry list of other add-ons like personal, carers and compassionate leave, community service leave and parental leave along with an open ended right that employers consider requests for ‘flexible working arrangements.’ Employees afflicted by domestic violence can already avail themselves of several of these categories.

Were we to top this off with an additional 10 days domestic violence leave, employees would be looking at 20 per cent of the entire year being covered by leave entitlements according to the Australian Chamber of Commerce.

Mathias Cormann drew venom when he pointed out that domestic violence leave would be another cost on business, but he’s quite right. Navigating the unwieldy laundry list of conditions and entitlements that comprise the modern award system already adds enormously to the cost of employing workers on top of headline wages figures.

At best, domestic violence leave will see an increase in Australia’s already high levels of absenteeism while putting HR staff in the unenviable position of determining whether an employees’ application for leave is bona fide.

At worst, it will see businesses further saddled with costs of fixing social problems even if it makes no demonstrable difference to the problem at hand. Indeed, with domestic violence now encompassing emotional and verbal abuse, it’s difficult to see even the most hardheaded boss risking the legal fallout of scrutinising a request, no matter how spurious.

In a broader sense, the domestic violence leave is symptomatic of a longer-running tendency to treat business and our industrial relations framework as part of the social welfare system. Indeed, in determining wage increases and minimum workplace entitlements, the Fair Work Act mandates that living standards and employee welfare must be guiding concerns.

Ironically, it is this very approach of using wage setting to optimise living standards instead of maximising economic growth and job opportunities that have in part produced well above trend long-term unemployment in the domestic violence hotbeds of Bourke, the Northern Territories Tennant Creek and Victoria’s Central Goldfields among many others.

At the end of the day, forcing employers to bear the cost of ever greater wages and entitlements does nothing to alter the iron law that employers will only hire workers whose contribution exceeds their cost of employment. For the long-term unemployed, low-skilled or young people languishing in the job-scarce fringes of our capital cities and regional Australia, every dollar added to the cost of employment builders a bigger roadblock in the path to finding work.

The alternative is to step back from using our workplace system to manufacture their vision of an ideal society and providing enterprise with the freedom to expand and realise its potential. This means more economic activity, more entry-level jobs and more people climbing the rungs of the workforce. In the long run, this means sustained demand for workers and in turn, higher wages buttressed by a booming economy.

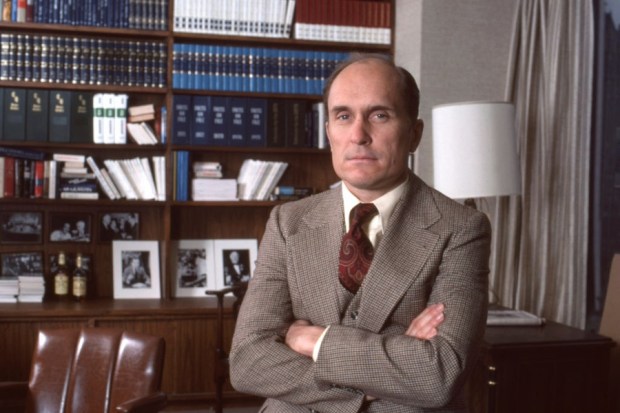

As President of the American Enterprise Institute, Arthur Brooks has argued ‘There is nothing more important to someone’s self-esteem than feeling like they are of value to others, and there is no better way to achieve that than through paid employment.’ Quite so — the dignity and purpose that comes with employment are one of the strongest antidotes to the maladies of idleness and social dysfunction so strongly linked with domestic violence. Sadly, the status quo hinders those without work far more than it helps them.

Trade unionists worthy of their mantle should spend less time moonlighting as social engineers and recast their eye to the reality of work, unemployment and social dysfunction in Australia.

Illustration – Pinterest.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.