Nude begins with that most perfect of bodies: champion archer Teucer drawing his bow, his youthful face absorbed in concentration, his lean, taut muscles – back, legs, buttocks – frozen in glistening bronze.

Teucer is a hero of the old world. But Sir Hamo Thornycroft’s statue was cast in the late 19th century. As the opening work of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Nude: art from the Tate collection, it shows the male physique at its most idealised: a spectacle of virile beauty.

Walk through the two hundred years of nudes displayed here, however, and the body perfect vanishes. In its place are proud bodies, ugly bodies, broken bodies. Bodies marked by age and excess and disappointment. ‘To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes,’ left embarrassed and exposed, Kenneth Clarke wrote in The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. The nude, by contrast, is ‘balanced, prosperous and confident’, as architectural as it is alluring. Over the years, then, the very icon of the ‘nude’ has been undressed.

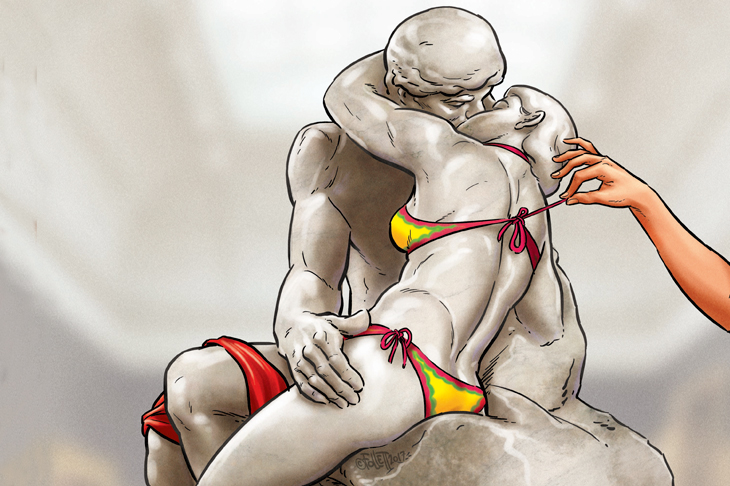

‘For as long as artists have been making art, they have put bodies at the heart of the picture,’ notes co-curator Justin Paton, who helped bring the works from the Tate to Sydney – including Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss. The decision to span the Victorian era to today is deliberate. It was a period, says Paton, in which the nude was ‘deeply and passionately’ debated, from its artistic merits to morals.

The results of those debates can be seen in Sir John Everett Millais’ The Knight Errant. The imposing 1870s oil canvas shows a handsome knight saving a naked woman tied to a tree in a forest. The contrast of textures is erotic: cascades of red hair and creamy white skin reflects off the hard silver of the knight’s sword and armour. As social conventions demand, the woman looks away meekly, hiding her shame. Millais’ damsel in distress was not always so demure, however. X-rays show that, once, she turned towards her knight. It was a brazen stare that was deemed too much for Victorian sensibilities: following bad reviews Millais removed the head and shoulders from the painting, replacing it with his new version. Nudes, it was believed, should exhibit unearthly grace: goddesses cast in marble who have always stood naked. Here, the woman is fleshy and ample and life-like: she has clearly had her clothes removed.

Such artistic tropes can be tracked, in part, to the models available at the time. Male life models could at least be associated with the warriors and gods of the Greeks and Romans. Being a female life model, by contrast, was viewed as a profession of ill repute, linked with prostitution, and fiercely disputed by some critics of the time (certain academies only used male models, leading elements of masculinity to creep into paintings of the female body).

While working with live nudes was an essential building block of artistic training, female artists were not allowed the same access. In Love Locked Out Anna Lea Merritt paints a small naked boy as Cupid – the only live model she could summon. Children were considered paragons of innocence who had ‘no sense of shame before artists,’ according to Merritt. (Today depicting naked children, even in art, remains one of the last standing taboos). Just three years later, in 1893, women were finally permitted to draw naked models, partially draped, in the Life Room at the Royal Academy.

Now, of course, nudity is everywhere, available to anyone at the click of the mouse. For Paton the 19th century was the moment when ‘many of the debates that are still with us emerge in the public arena.’ Today he observes the same ‘absolute obsession with bodies, this curious mix of prudishness as well as permissiveness. They too were contending with a tsunami of new images of the body because photography has just been invented. With the Internet we confront similar challenges – what is high art to do in the face of this deluge of digital bodies?’ What constitutes ‘high art’ has always been in question. The Kiss may be one of the most romantic sculptures of all time – with two lovers entwined in smooth marble, lost in lust – but it was once viewed as salacious. In World War One the sculpture was covered up by moral guardians who believed the sight of it would inflame the desires of the troops stationed in the town nearby.

It is easy to scoff, but censorship remains today. In 2012 a poster of Picasso’s juicy, warm Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (1932) was banned at Edinburgh airport. Facebook recently removed the Pulitzer-Prize winning photo The Terror of War of a girl fleeing unclothed down a Vietnam street. Both decisions were revoked, but it’s telling that the naked body still causes such unease.

In the 20th century that unease was exploited to create works taut with tension. One example is Pierre Bonnard’s The Bath (1925) in which his wife lies yellow, almost sickly, in a white bathtub that resembles a tomb, the water as her shroud. More confronting still is Sir Stanley Spencer’s 1937 Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and his Second Wife. Spencer squats over his wife as if over an altar. She reclines beneath him, beside a thick leg of raw mutton. Both are naked, unflatteringly so, with sprawled genitals, tufts of pubic hair, and sagging stomach and breasts. The work is painful: it is a depiction of sexual yearning (the marriage was reportedly unconsummated) and emotional distance, set in cold British lodgings where a fire barely heats the room.

Sylvia Sleigh’s Paul Rosano Reclining (1974) shows a man stretched out like a male Olympia for the delectation of female viewers. Rather than the smooth and hairless ideal of a classical nude, however, he sports a full afro, a body covered with hair, and a meaty, limp sex organ. A real, breathing, living man.

Nude ends as it starts: with a naked male statue dominating the final room. While Teucer is assured and athletic, Ron Mueck’s gargantuan Wild Man (2005) is afraid. Utterly exposed, he grips his chair with both hands and curls up his toes, his eyes darting with terror.

‘It is a work about being looked at,’ says Paton, ‘a contrast to the heroic bronze who is buff, handsome, and confident.’ As critic John Berger once noted, ‘Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in