Ernest Hemingway loved going to the zoo, but not on Sundays. The reason, he explained, was that, ‘I don’t like to see the people making fun of the animals, when it should be the other way around.’ He would probably have enjoyed Animality, an entertaining exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery, Lower John St, W1. It contains quite a few jokes, but generally the laugh is on Homo sapiens.

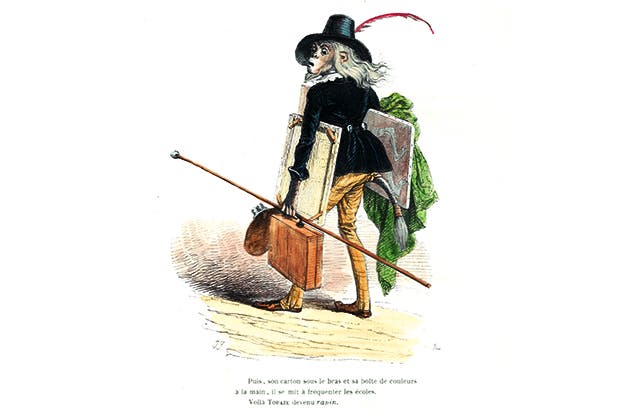

The humour tends to comes from an age-old ploy: birds, reptiles and mammals wearing clothes. It was the basis, for example, of many works by the caricaturist J.J. Grandville of cats, bears and other such fauna dressed up as early 19th-century French citizens.

The contemporary sculptor Stephan Balkenhol carries out the same metamorphic prank with a couple of wryly weird figures on plinths: one with very hairy legs, shorts, T-shirt and the face of a fox. Yinka Shonibare contributes a life-sized, gun-wielding, beast-headed acrobat balanced nimbly on a tightrope.

Of course, this is Beatrix Potter territory, but even such comforting characters as Mrs Tiggy-Winkle are slightly ambivalent. We find the hedgehog in a dress charming, but there is also the implication that we ourselves are — as Lucian Freud half thought of his non-naked sitters — ‘animals dressed up’.

This exhibition is about the boundary — one that becomes less clear the more you think about it — between humans and other species. It also tinkers with the borders between art and non-art, past and present. Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut of a Rhinoceros is included, and Walt Disney’s Jungle Book too — along with several pieces of recent video art.

Many of the most striking images are 17th- and 18th-century zoological illustrations — which used to be thought merely scientific, but are also often both strange and beautiful. The funniest exhibit, however, is the biggest. John Baldessari’s ‘Camel (Albino) Contemplating Needle (Large)’ (2013) is a biblical metaphor in three dimensions and a neat exercise in a very up-to-date genre: the ironic monument. The camel is full-scale and the eye of even a giant needle not nearly large enough.

There is greater monumentality, but no irony whatsoever, in the recent work by the American sculptor Richard Serra on show at Gagosian, Britannia Street, WC1. Serra’s work is all about non-amusing qualities such as gravity, and massiveness. His affinities, he has said, are with ‘the monuments of death’: sarcophagi, Inca architecture, the Michelangelo of the Medici Chapel.

The largest piece in this show, ‘NJ-2’ (2016), is the size of an ocean-going ship — and looks a bit like one too. From one end it looms above you like the bows of a boat, its steel surface rusted to a velvety orange. This is a sculpture to explore as one might an ancient tomb or some desolate industrial ruin. You walk into a cleft in its side and the towering walls close above your head, squeezing the space like a narrowing cave. Round the next curve the steel sides open out, then tilt to one side, and so on — now more claustrophobic, now less — through the labyrinth. You come out at the other end, having traced a path you can’t quite comprehend, though the gallery helpfully provides a map.

‘NJ-2’ (2016) dominates the gallery, grimly, and would look very much at home in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern (except that the Tate currently seems less interested in visual grandeur than in an artistic variety of political correctness that suddenly seems old-fashioned). The other pieces in the show are smaller, though that is relative. ‘Rotate’ (2016) consists of two rectangular slabs of steel, lying side by side like a couple of gigantic imperial coffins — except that these are not boxes but completely solid. Serra wants you to sense their weight — and somehow you do.

The surfaces of his sculptures are the product of the processes by which they are made — some are rolled in enormous machines designed to construct the hulls of warships — but the accidental flecks, streaks and mottling that result are nonetheless beautiful.

Serra explores similar effects in the works on paper on show at Gagosian’s Davies Street gallery, W1. ‘Drawing’ is scarcely the word for these densely black, thickly built-up layers of ink, crayon and paint-stick on sheets thicker than a blotting-pad. They are more like very thin sculptures. As always with Serra, you have the impression of encountering something extremely obdurate.

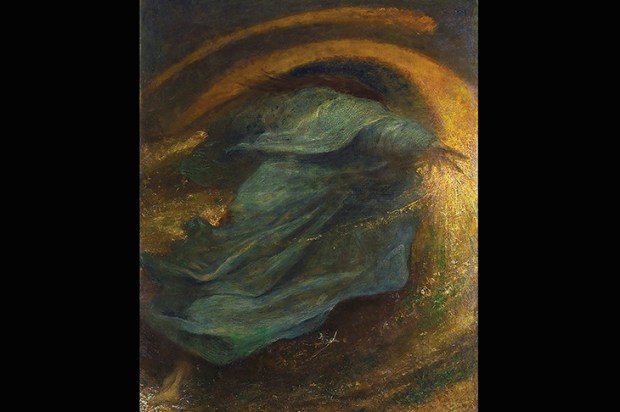

The art of Vicken Parsons is in several ways the opposite of Serra’s. The new works in Iris, her exhibition at the Alan Cristea Gallery, Pall Mall, SW1, are not tough and menacing but unobtrusive, subtle and reticent. Instead of heavy metal by the ton, her chosen medium is thin paint on meticulously sanded pieces of plywood, a foot or two across.

You need to look at these little paintings from close-up, intimately. When you do, initially you may think she is an abstract exponent of oblongs and straight lines — a slightly fuzzy, small-scale descendant of Mondrian.

Actually, she is that — but in art you can be two contradictory things at once. And a second glance reveals a series of light-filled spaces. Instead of patches of paint, you suddenly see doorways, windows, one empty room opening into another, pools of sunshine gleaming on the floor. There is a distinct emotional tone there as well: quiet, still and a little eerie. At first you scarcely notice it, then it grows on you. So does the notion that Parsons is an intriguing and underrated painter.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in