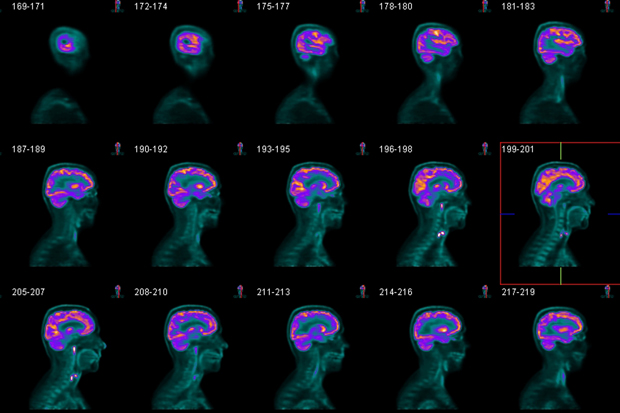

In the cult Steve Martin film The Man With Two Brains, a doctor falls in love with a surgically removed brain. The object of his desire (fizzing, if I remember rightly, in a demijohn of formaldehyde) makes for an enduring gothic comedy of the mind. On the movie’s release in the early 1980s, neuroscience was still in its infancy. Men in white coats were cutting up monkey brains and their laboratories smelled of monkey urine. In recent years, however, neuro-imaging has changed the study of the human mind completely. Rainbow-coloured images on the scanner screen reveal our most precious and mysterious organ in all its alien complexity.

Computer imaging may yet fathom the mystery of epilepsy. From the Greek ‘to capture’ or ‘to seize’, epilepsy is commonly viewed as a rather spooky disorder, associated at times with demonic possession. The real causes for epilepsy remain unknown. Colin Grant’s A Smell of Burning, a

flawless amalgam of personal memoir, mind science and medical history, casts a sympathetic eye on those afflicted by the condition. The author’s younger brother Christopher died in 2008 from a heart attack attendant on a prolonged seizure — in status epilepticus. As well as being a superlative socio-medical history, the book commemorates the life of a much-loved sibling.

Grant, the son of Jamaican immigrants, grew up in Luton in the early 1970s and went on to become a medical student at the London Hospital in Whitechapel. His absentee father worked for Vauxhall Motors while his long-suffering wife, Blossom, struggled to feed her five children and buy them shoes. Christopher’s epileptic blackouts were associated in her

Pentecostalist-Revivalist mind with visitations from the Beyond; they threatened to bring down shame and scandal on the Luton family home.

A number of famous people have suffered from what the ancients termed the ‘falling sickness’, among them Lenin,

Dostoevsky, Graham Greene, Emily Dickinson, Edward Lear, George Gershwin and (most likely) Julius Caesar, Dante and Joan of Arc. Neil Young, the godfather of grunge, has steadfastly refused medication for the past 20 years. In the late 1960s he was subjected to ‘excruciating’ neurological tests after an epileptic fit felled him on stage: never again. Another confirmed epileptic, Ian Curtis of the Manchester post-punk band Joy Division, was thought to mimic epilepsy’s convulsive onset in his jerky, spasmodic dance routines. His hit single, ‘She’s Lost Control’, is a fear-ridden hosanna to the disorder.

In a fascinating chapter, Grant explores the olfactory hallucinations that often precede an attack. Powell and Pressburger’s 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death, in which a crashed bomber pilot develops an undiagnosed neurological condition, was ‘pioneering’ in its depiction of epilepsy and the pre-epileptic aura. The pilot, played with gracious suavity by David Niven, speaks repeatedly of a phantom smell of ‘fried onions’.

Grant’s brother had also obdurately declined medication, only to crash his car following a blackout. I must say the episode provoked a feeling of unease in me. This August in the Lake District I blacked out at the wheel of my car, swerved off the road and crashed into a house near Beatrix Potter’s. My wife was airlifted to hospital with a fractured spine and near-fatal flail chest. (The car was a write-off). Pending neurological tests, the DVLA has banned me from further driving. What happened exactly? It’s something of a brain teaser.

In Grant’s account, however, epilepsy may arise as a result of brain lesions caused by an old trauma, ‘such as a blow to the head’, when damage is done to the brain’s fragile connectivity maps. Thirty years earlier in Rome, I underwent surgery for an epidural haematoma after an unexplained fall. The accident left me with no permanent side-effects but I wonder now if epilepsy had not taken hold on that quiet Cumbria road.

A Smell of Burning, based on interviews with epileptic patients and archival research conducted in hospitals and libraries, is one of the finest works of non-fiction to come my way in a long time. Not only is it exquisitely written, but it radiates a deep and affecting compassion.

The post Blackouts and white coats appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in