Suitably for a year so full of cataclysms and disturbing portents, 2016 is the quincentenary of the death of Hieronymus Bosch. He was of course the supreme painter of hell, with choking darkness, livid flames and the most grippingly monstrous menagerie of devils in the history of art — duck-billed figures on skates, demons with bat’s wings, lizard’s claws and cat’s whiskers. His panoramic vista of naked humanity inflamed by desire in ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ features giant birds and fruit, weird mineral formations, and — in one case — a couple making love in a cosy mussel shell.

An Italian traveller who saw this masterpiece in 1517, noted — correctly — that it is impossible to describe Bosch’s work satisfactorily in words. The more you look at these pictures, the more you see. Those who wish to explore it are recommended to do so in the learned texts and splendid images of Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Catalogue Raisonné (Yale £99.99), which condenses six years of meticulous research by a team of scholars, the Bosch Research and Conservation Project. Hieronymus Bosch: The Complete Works (Taschen £27.99), also lavishly illustrated, is a less expensive alternative, slightly different, take on the same subject.

Bosch’s art, though ostensibly religious, surprisingly often seems to be about sex (and consequent damnation). Splendours & Miseries: Pictures of Prostitution in France 1850–1910 (Flammarion, £35), the catalogue of last year’s exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, makes clear that in fin-de-siècle Paris, sex — or at least what we now call sex workers — had become a much bigger subject than religion. It presents and analyses numerous depictions of brothels, streetwalkers and grandes horizontales, among them such masterpieces as Manet’s ‘Olympia’ and Picasso’s ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’.

The history of pictures, as David Hockney and I have argued elsewhere, is wider and stranger than the conventional history of art. One of its fascinating and neglected episodes is considered by Georges Vigarello in The Silhouette from the 18th Century to the Present Day (Bloomsbury £30). In effect, a silhouette was a way of making a shadow permanent. A line was traced around the sitter’s profile, which was then cut out of black paper.

The result condensed the essential appearance of an individual. Thus early silhouette portraits were handmade predecessors of photography: quasi-mechanical images. Vigarello describes the way the silhouette affected 19th-century caricatures and what eventually became the art of the comic book. He ends — more contentiously — by suggesting that our contemporary obsession with bodily slimness and sleekness has its origin in this Georgian fad.

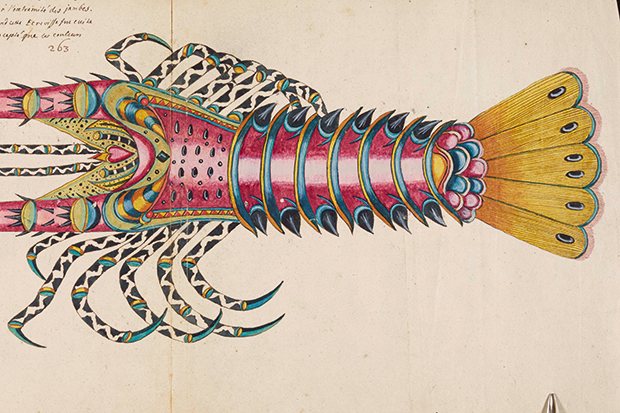

Watercolour of a crayfish for Poissons, écrevisses et crabes, published by Louis Renard 1718–19. The handwritten notes indicate that the artist ate it against the advice of experts, with no ill effects. Illustration from The Paper Zoo

Pictures can be sources of knowledge. Without them, indeed, some studies would be difficult or impossible to pursue. How could you define and describe innumerable types of animals, birds and insects using words alone? Charlotte Sleigh, a historian of science, takes zoological illustration as her theme in The Paper Zoo: Five Hundred Years of Animals in Art (British Library, £25). Some examples are as cute as the title might suggest. Others, such as Robert Hooke’s drawing of a louse clinging to a human hair seen through a microscope in 1665, distinctly less so. But although accuracy, not beauty, was their point, many are nonetheless beautiful.

This year has not been the most festive of years, one way and another; but the prize for the volume least full of seasonal cheer goes to a paperback edition of Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death (Penguin £9.99). In a way, this was one of the first art books, designed for wide distribution at a relatively cheap price. As such, it’s an appropriate choice to be the initial Penguin Classic consisting largely of pictures (though also including a commentary and brief biography of the artist by Ulinka Rublack).

Holbein designed this series of miniature woodcuts in Basel, before he ever set foot in England. In each episode a spritely, almost jaunty, skeletal figure comes to visit someone — urging the ploughman’s team of oxen towards the setting sun, playfully seizing the miser’s gold, running the knight through with his own lance. It would make a macabre stocking-filler.

A less gruesome but also less visually appealing candidate for that role is ‘Art is the Highest Form of Hope’ & Other Quotes by Artists (Phaidon £14.99). This consists of a diverse assembly of pensées by creative types, arranged by topic and printed in large type in the manner of the strand of 1970s conceptual art that consists entirely of words. Not all of these collected musings are as upbeat as the title (a thought expressed by the contemporary painter Gerhard Richter). Those with a gloomier outlook might prefer this rather excessive moan from the notoriously grouchy Michelangelo (from the ‘money’ section):

Painting, sculpture, hard work and fair dealing have been my ruin and things go continually from bad to worse. It would have been better had I been put to making matches in my youth.

This Christmas Day will you be sitting down to eat from a plate decorated with a Renaissance painting of Venus or Mary Magdalene? Probably not, but at a feast in 15th- or 16th-century Italy you might well have done just that. Or so at least it is argued by Luke Syson in an essay in Timothy Wilson’s handsomely illustrated catalogue of Majolica: Italian Renaissance Ceramics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met Publications, $75). At once gaudy and sumptuous, majolica is not to everyone’s taste. Those who are allergic to the idiom might feel it would put them off their food. Majolica-lovers, on the other hand, would possibly relish seeing an idealised nude or Biblical scene appear from beneath their soup.

A still more bizarre dining experience is promised by Salvador Dalí’s Les dîners de Gala (Taschen, £44.99), a cookery book originally published by the veteran surrealist in 1973. The accompanying photographs, drawings and paintings are luridly over-the-top, and the chapter headings — ‘les entre-plats sodomisés’, for example — gamely outrageous. But the actual recipes — ‘roast side of beef with vegetables’, ‘crayfish consommé’ — often seem disappointingly edible.

The post A choice of art books appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in