‘I really, really hate rats,’ Sir David Attenborough has boasted. ‘If a rat appears in a room, I have to work hard to prevent myself from jumping on the nearest table.’ But why? Sir David’s answers are disappointingly feeble. A rat had once run across his bed. They live in sewers. They show no fear and ‘invade the area where you think you are boss’.

It is odd that a naturalist can hate an animal for simply doing what animals do — survive — and rather better than most. But almost everything about how humans view rats is illogical. Any social historian looking to prove that an ounce of primitive emotion will outweigh a pound of rational thought should study our creepy rat phobia, as unchanging down the years as it is unthinking.

Rats are a miracle of evolution —resourceful, intelligent and generally fascinating. And yet they are loathed more than any other animal on earth. Our attitude is strangely medieval, and we’re proud of it. Even the kindest, most reasonable of people will cheerfully brag of their prejudice. A regular stand-by for tabloids is a story about ‘super rats’, invariably illustrated with a false-perspective photograph. Recently, the Guardian devoted its ‘Big Read’ spot to ‘Man vs Rats’, describing the animals as ‘our perfect nightmare’.

There is nothing new in this madness. The French biologist Léon Calmette, in his 1904 paper Declarons la guerre aux rats, announced that if rats weren’t exterminated, they’d bring about the end of humanity. They appear in villainous roles in literature, notably crawling all over the works of Orwell. ‘Of all the horrors in the world – a rat!’ gasps Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

A famous New Yorker piece called ‘The Rats on the Waterfront’, written in 1944 by Joseph Mitchell, listed the usual hysterical claims: rats kill babies, try to eat vagrants, bite the necks of chickens out of a sheer lust for killing. Apparently, they also ‘snarl’. (Snarl?)

According to other reports, there are no limits to a rat’s sins. One claims they are so sex-obsessed that they will mate with a corpse; another that they are motivated by greed and hedonism. A rat-catcher in Morgan Spurlock’s new documentary Rats swears they can read the warning signs on packets of poison.

Yet the more I have seen of these astonishing animals, the more I have come to admire them. When I was small, my brother had a pet rat called Whiskers that he kept inside his shirt. It was loyal; when placed on a table and surrounded by humans, Whiskers would sniff everybody’s hands before running up his master’s arm. Years later, my son Xan had a similarly endearing rat called Jaboa. For its last night on earth — it contracted respiratory disease, a common problem among pet rats — it slept on my bed.

I see wild rats several times a week and occasionally, when their presence around our hen-house becomes a problem, have to kill them with the help of my brilliant ratting dog (a more humane method than poison or an air-gun in my experience). I admire them, even as enemies. Their reaction when cornered is not to run or attack, but to freeze and try to make themselves invisible. They are lithe, good jumpers and superb swimmers. I am impressed by how they use anything and everything to survive, gaining sustenance from gnawing on old bones, plastic or the glue on books, adapting to whatever a hostile environment throws at them.

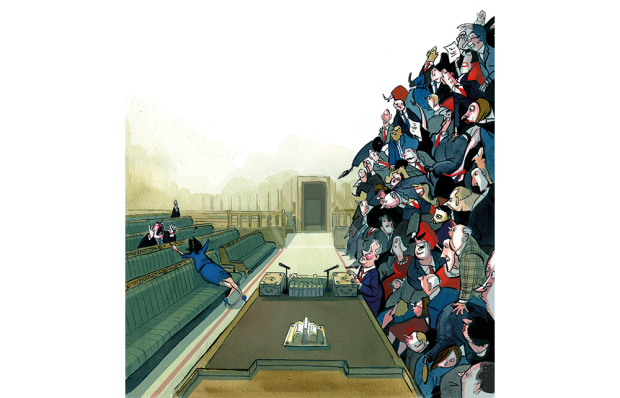

Such is my fascination, and the irrational fear that rats engender, that I wrote a novel called The Twyning, set in 19th-century London, in which rats are the heroes while humans, except for two abandoned teenage children, are the aggressors. From a position of bias, I think my epic tale — I envisaged it as a ratty War and Peace — would make a more interesting film than Spurlock’s gross-out documentary, which Variety magazine described as a ‘grisly marathon of murder’, pointing out that every trick in the book is used to quicken viewers’ disgust for its subject.

Of course, in parts of the world, rats are a menace, eating food humans grow for themselves, causing environmental damage and spreading disease. But none of that explains our paranoiac fear.

There is, after all, so much to admire. In a recent experiment, scientists at the University of Chicago discovered that, like humans and intelligent apes, rats have empathy. Given the choice between a chocolate treat and freeing another caged rat — one it has never seen before, incidentally — a lab rat will choose the noble path.

Perhaps behind our sinister hatred there lies an uncomfortable truth. Rats are clever and exploit the world around them for their own ends. They are competitive with other species. They are highly sexed and mate all year round.

Remind you of anyone?

The post Of rats and men appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in