As a chat-up line it was at least unusual. On 8 January 1927, a 46-year-old man approached a young woman outside the Galeries Lafayette department store in Paris and announced, ‘You have an interesting face; I would like to do your portrait. I feel we are going to do great things together.’ The approach was successful, even though the woman in question, Marie-Thérèse Walter, was bewildered by his subsequent announcement, ‘I am Picasso!’, since she had never heard of the famous artist.

Undeniably, great works did result from this chance meeting — as well as an intense affair, which lasted for years. Several are included in the splendid Picasso Portraits exhibition at the NPG. Marie-Thérèse appears in multiple guises: as a majestic bronze head from 1931, a tenderly intimate pencil drawing of 1935, as the subject of ‘Woman in an Armchair’, a large oil from 1932, with colours borrowed from Matisse, in which her anatomy is rearranged so that her head is in profile but not her torso.

These are all, in their quite different ways, marvellous works of art. Some, however, might quibble about two matters. First, are these all really portraits? And second, were they truly done ‘together’ with the subject? That is, was she truly a participant in their creation?

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) certainly had an idiosyncratic conception of portraiture. For him, it was not so much a question of getting a conventionally recognisable likeness — though he sometimes did that too. Certain faces, bodies and personalities permeated his consciousness so completely that at times everything he made was — in an extended way — a portrait of the person who was on his mind. Marie-Thérèse so pervaded his art at one point that even a still life of a jug and fruit turned into her softly voluptuous forms.

Perhaps wisely, the exhibition does not include such portraits in disguise. Even so, the range of permutations of the form on display is very wide. For example, Picasso’s earliest portrayal of his first wife, the ballerina Olga Khokhlova, ‘Portrait of Olga in an Armchair’ (1918), was a brilliant pastiche of Ingres. In contrast, Olga’s final incarnation, ‘Woman in a Hat (1935)’, painted after the marriage had broken down, is a series of geometric shapes in bilious colours, from which two black discs of eyes stare out, with a short, oblique line for a mouth below.

The question arises: which of these was the best likeness? The answer might be: in a way, the second. As Elizabeth Cowling, the curator, points out in the excellent catalogue, ‘Portrait of Olga in an Armchair’, though done from a photograph, deprived the subject of the dancer’s energy and alertness that the camera had caught. In the painting, she seems listless and melancholy: how Picasso saw her or wanted to see her, perhaps, rather than as she was. The almost abstract ‘Woman in a Hat’, on the other hand, perfectly catches the tension and anxiety that was all that was left of their relationship by that point.

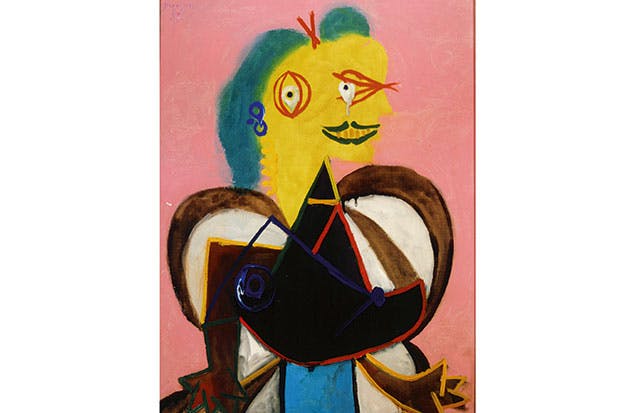

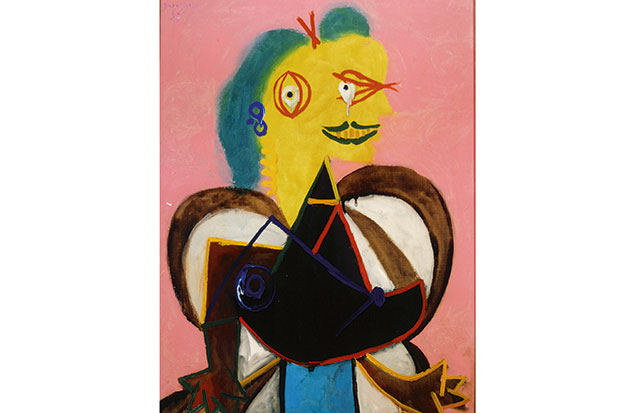

Picasso had a remarkable ability to create a resemblance from the most improbable ingredients. ‘Portrait of Lee Miller as l’Arlésienne’ (1937) is remarkably dissimilar from the chiselled art-deco beauty who can be seen in Man Ray’s photographs of Miller from a few years before. It presents her grinning manically with green hair and lips, banana-yellow skin and pink teeth. One of Miller’s eyes is placed vertically about where you might expect to find an ear. Yet her lover, Roland Penrose, described it as ‘an astonishing likeness …put together in such a way that it was undoubtedly her’, and reported that their infant son shouted ‘Mummy, Mummy’ when he saw it.

From an early age, Picasso famously recalled, he had been able to draw like Raphael. Brilliant draughtsmanship in the classical tradition is certainly on display here, notably in a superb portrait of Stravinsky from 1917, pared down to a minimum of sharp lines like a Greek vase painting.

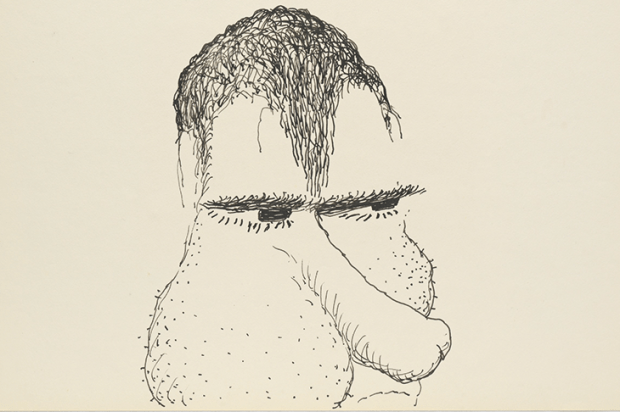

From early on, however, Picasso also had a knack of exaggerating certain traits to create a likeness that was a little like a cartoon. He acknowledged as much: ‘There are so many realities that in trying to encompass them all, one ends in darkness. That is why, when one paints a portrait, one must stop somewhere, in a sort of caricature.’

That is part of the brilliance of Picasso, but it also explains the misgiving one sometimes has that he is not being quite fair to the subjects. Instead he is exploiting them, making fun of them — as he did constantly with his loyal friend Jaume Sabartés. As Lucian Freud pointed out, Picasso was a showman, always keen to amaze and surprise the viewer.

In that he certainly succeeded, which is what makes this exhibition both fascinating and hugely entertaining.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in