All organic beings descended from a single primordial blob, according to Darwin. Some of them developed sufficiently to leave the commodious depths and widths of the sea to scramble ashore. Was that wise? In this intricately detailed history, David Miles, a distinguished Oxford archaeologist, takes up the story of human evolution since our species and chimpanzees diverged from a common ancestor about seven million years ago. Between the origin of our life on Earth and the exponential population growth that causes long queues and traffic jams and threatens imminent apocalypse, there was a period when change amounted to beneficial progress.

Miles is well qualified by his experience as director of the Oxford Archaeological Unit, chief archaeologist of English Heritage, archaeological adviser to the Bishop of Oxford and author of numerous excavation and survey reports. He presents his scholarly findings with glints of good-humoured individuality which make his book pleasantly readable, even by lay persons who may not previously have paid much attention to the differences between Palaeolithic and Neolithic tribal behaviour.

His work is enhanced by technologically innovative probing for fossils, animal and human remains and artefacts, and by classifying them with the aid of carbon dating. As he recalls his research on extensive field- trips in Britain and abroad and the conscientiously acknowledged research of other archaeologists, his enthusiasm is infectious. The more that he discloses of the deep past, the clearer it becomes that our distant ancestors were less primitively inept, more capable, physically and mentally, than popularly imagined.

‘The Neanderthals,’ he writes, ‘have often had a bad press as primitives who went extinct.’ He persuasively defends them against charges of uncouthness. Like many other misinformed controversialists, ‘the US Republican politician Sarah Palin referred to one of her opponents as a “knuckle-dragging Neanderthal”’ .Even the OED defines Neanderthal secondarily as an informal term of abuse. However, Miles points out, Neanderthals walked upright and had ‘stocky bodies, like weightlifters or prop-forwards in rugby’, and survived an ice age in the company of mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses until about 40,000 years ago. He adds:

To a certain extent, Neanderthals live on. Their genes make up 1–4 per cent of non-African humans today. This suggests that when humans first came out of Africa into the Middle East some interbred with Neanderthals, then carried the Neanderthal genes to regions the Neanderthals themselves never reached.

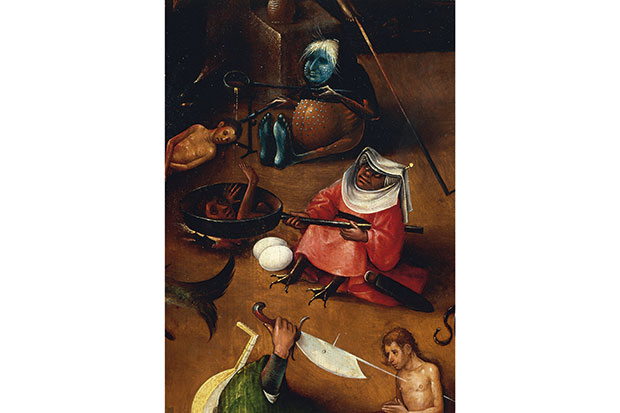

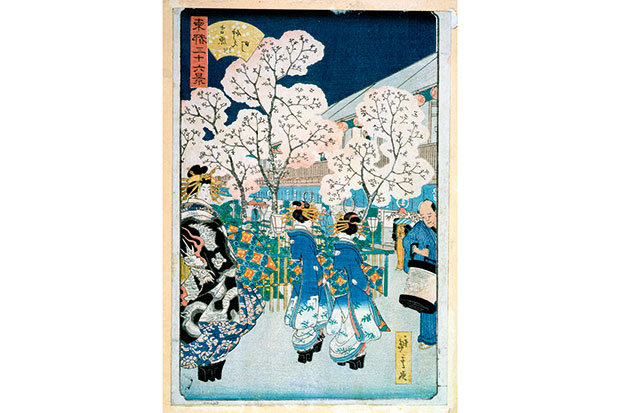

Miles discovered evidence that the developing human brain ‘from about 100,000 years ago began to think symbolically, and created music, stories, art and religious beliefs’. After a hard day of foraging, the contemplation of aesthetics must have allowed some welcome relaxation. Some 4,000 years ago we had already turned from procuring to producing food. In the milder climate of the late Stone Age, Neolithic immigrants settled down in England to cultivate crops, especially grains, and domesticate animals. Farming was laborious and monotonous compared with nomadic hunting and gathering, but provided a relatively predictable food supply and made it possible to raise large families and build villages for protection and conviviality.

As communities grew, the dominant members of social hierarchies demanded the higher status of more elaborate shelters, grander tombs and bigger memorial circles of standing stones. Artisans, who had been hacking and chipping rocks into rudimentary axes for centuries to use as weapons and woodcutting implements, were encouraged to refine axes beyond mere utility, to be treasured as household ornaments and talismans. Miles has chosen a smoothly polished axe head, made of olive-green Langdale tuff quarried in the Lake District, as the focal emblem of Neolithic civilisation and the title of this enthralling book.

Backward-looking wistfulness is intensified by consideration that humans were probably better off before the Stone Age. ‘Their numbers were few,’ Miles observes, ‘until they spread out of Africa,’ the first home of our species. ‘Even then, hunters rarely averaged more than one person per square mile.’

In contrast, in 2016, he gloomily recognises that

The world faces a crisis of rising temperature and sea level, environmental destruction, species extinction, extreme weather events, fires, water shortage, soil deterioration and desertification. Industrial farming is a major contributor to these problems, producing food but with enormous energy costs and making no sustainable sense. Livestock rearing is itself a major producer of the principal greenhouse gases — carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — which drive global warming.

His descriptive prose, with illustrations in colour and black and white, animates Neolithic bones in this portrayal of the good old days before senile dementia and the canned laughter of sitcoms.

The post The axeman cometh appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in