On 8 June 1920 an old beggar woman sat against a wall in Kingsway holding a mongrel in her arms and singing aloud. Virginia Woolf noted in her diary that there was a recklessness to her. She was singing for her own amusement, shrilly, and then fire engines came by singing shrilly, too. ‘Sometimes everything gets into the same mood; how to define this one I don’t know.’

In the mid-1980s, on my daily journey to Charing Cross Road, I would get off the 38 bus on the corner with New Oxford Street. Every morning I would see an old woman huddled in the doorway of what is now a building site. Enthroned on her rags, oblivious to her surroundings, she had stopped caring. In her diary that day, Woolf said she was overwhelmed by the dead walking the city streets. I wondered where this woman came from and how she had settled on this doorway as her home. Perhaps another of Woolf’s ghostly tenants had passed down the leasehold to her successor.

The concept of the aimless wanderer, observer and reporter of street life, was first taken for an outing by the French poet Baudelaire. His flâneur was an extension of himself: an aesthete and dandy, wandering the streets and arcades of 19th-century Paris, noting down graffiti and advertisements and listening to snatches of conversation, on the lookout for visual rhymes. Traditionally, the flâneur was male, since women were confined to the domestic sphere, and any such constraint is inimical to the wanderer’s aim.

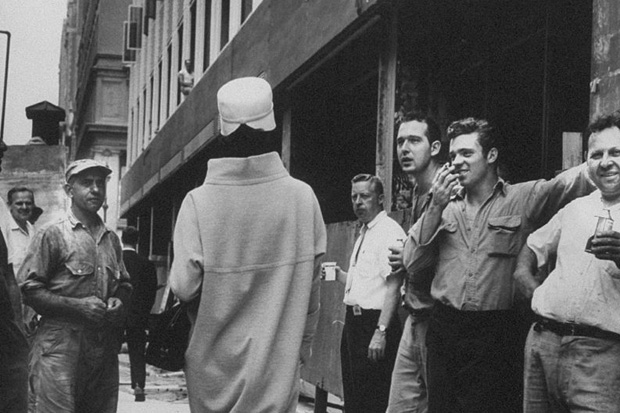

In this memoir of her postings across three continents, the novelist and critic Lauren Elkin contemplates what it means to be a woman taking on the role of loafer. For the most part, her findings reveal that the female flâneur — or flâneuse, as she prefers — has to withstand the inquiring gaze of admirers and admonishing prudes and predatory hasslers. According to Elkin, it is a rare woman who prowls the streets in the guise of an artist. She cites George Sand on the revolutionary barricades (dressed as a man) moving on to the modernists, Jean Rhys and Virginia Woolf, and the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn. These were women, Elkin asserts, who were prepared to forego their visibility or flaunt it, rather than report it. At times, it is hard to see what exactly of the female walker’s nature there is to report — apart from diversions provided by men.

Walking, as Thoreau said, inevitably leads to other subjects. A history of female pedestrianism should unfold like a walking meditation in which a woman aligns herself with the world. Unfortunately Elkin loses the novelist Jean Rhys down a dark alley. She quotes Rhys saying ‘I can abstract myself from my body’ without fully appreciating what she means. Walking for Rhys was a search for sensation, an avoidance of self, as well as the hope that she might bump into a man who would buy her dinner. In this latter instance, Rhys was driven by economics rather than wanderlust.

Elkin herself begins her journey in the affluent ‘non-place’ of Long Island, surrounded by the safeguards of protective, high-status parents and low-rise shopping malls. When she does get to New York, she is distracted by male interest in her body —the occupational tripwire of the flâneuse. She reaches solid ground recording the concerns of the photographer Sophie Calle, whose flânerie in the space left by Baudelaire casts her as a stalker rather than a walker. Calle’s art finds her having lost herself attached to a man. Elkin follows suit when she follows a banker boyfriend to Tokyo — and describes the longueurs she experienced there.

A woman defining herself through or evading the male gaze is the dilemma that drives Elkin’s quest. But the writers she quotes mark their territory as limitless. If Rhys was dead to herself, she was not dead to the city, and in finding anonymity she found her artistry. For Woolf, ‘the champagne brightness of the air’ sparked a heightened awareness, resulting in the ‘leaden circles’ of Big Ben dissolving around Mrs Dalloway.

Elkin makes room for the confessional and declares the right of the flâneuse to assert herself. But her writing rarely lifts off the page. To get the drift of a real wanderer-poet is to be shot through with texture and momentum. This is prose that should be layered with mystery and memory; that suspends the past and makes immediate our present. The flâneur transcends the city limits. Elkin stays strictly within.

The post Girls about town appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in