Peter Ho Davies’s second novel, The Fortunes, is a beautifully crafted study, in four parts, of the history of the Chinese in America. Though it deals, of necessity, with racism in all its insidious forms, it does so with humanity, humour, self-deprecation and a hefty dose of irony. Each section — ‘Gold’, ‘Silver’, ‘Jade’ and ‘Pearl’ — covers a separate period in Chinese-American history.

‘Gold’ follows Ling, a half-white upwardly mobile immigrant, who arrives before the Civil War, starting as a laundryman and progressing to become the valet of one of the four big barons of the Central Pacific Railroad. On the way he falls in love with a prostitute, Little Sister, and has his queue cut off by a fellow Chinese to whom he has been attached in a race riot.

The loss of his hair triggers in Ling a desire to pass himself off as almost white — as a ‘ghost’ or a ‘devil’ — until he unexpectedly recovers his Chinese identity while accompanying his master, Crocker, in an attempt to break a strike of Chinese railway workers. It had been Ling’s quick thinking that had encouraged Crocker to consider hiring Chinese ‘coolies’ in the first place, when they had previously been assumed to be too weak for the job.

Ling later becomes a powder man (responsible for explosives on the railway), and ends his days as a bone-scraper, tasked with collecting up the bones of dead Chinese railway workers and sending them home to be buried alongside their ancestors.

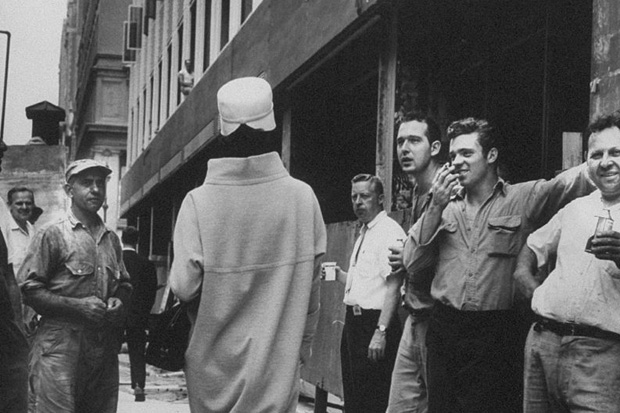

‘Silver’ tells the story of Anna May Wong, the first Chinese movie star in America. Despite her high status as a Hollywood actress, in real life Wong encountered racism at every level. In Davies’s account, she somehow manages to transcend her environment through style and sheer force of will, but, on a visit to her father in Shanghai, she finds that she is neither one thing nor the other. To the Nationalist Chinese she is American, and to the Americans she is an exotic foreign dish. Douglas Fairbanks Sr, with whom she had one of numerous high-status affairs, called her the ‘chink in his amour’.

‘Jade’ transports us to the 1980s, and the brutal murder of a Chinese man by two whites. The killers, who had beaten the man to a pulp with a baseball bat, got off with probation and fines of $3,000 each, plus court costs. They had assumed, falsely, that Vincent, their victim, was Japanese. His friend, who tells the story, had ‘scrammed’, thereby saving his own life. Later, in a telling irony, he becomes a founder member of the ACJ (American Citizens for Justice), a pan-Asian political movement fighting for equality of opportunity.

The final section, ‘Pearl’, interleaves with the first three — which may be part of author John Smith’s imagination. Again we’re in the realm of interracial disharmony, when Smith, the half-Chinese narrator, and his white wife, Nola, travel to China to adopt a child. John fears he is a ‘banana’ — yellow on the outside, white on the inside. He doesn’t even speak Chinese. He feels that the other (white) adoptive parents they meet resent him because ‘he looks the part’. But he has never even dated a Chinese girl. Nola was his ‘occident waiting to happen’. While she sleeps, John is drawn to a prostitute, Pearl — but ends up simply talking to her.

When the other adopters receive their babies, John and Nola find themselves bereft. The baby they had seen in the photograph does not appear. When they are offered a substitute, they remonstrate; only to discover that Mei Mei — their intended — had died that morning. Nola insists on seeing the dead baby — after which they are taken to the crib room and allowed to choose whichever child they like, as a sort of compensation. But they cannot. They don’t want to ‘choose’; they want to be ‘chosen’. Which they are, eventually, when Nola feels her finger in the tiny grip of another baby that has been placed in her arms. At John’s suggestion they call her Pearl, after the prostitute he befriended, and whose existence he has kept to himself.

Davies’s first novel, The Welsh Girl, published in 2007, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and he was adjudged one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists. The Fortunes is an equally beguiling book, and should do much to strengthen Davies’s reputation.

The post Chinese whispers appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in