Dom Perignon, Pimms, Carling Black Label, Coca-Cola — one’s as good as the other, so far as they’re concerned. Even if they don’t manage to drown in the stuff, they spoil the taste for drinkers by creating panic out of all proportion to their size. They destroy the ardour of al-fresco lovers in an instant. They are the joy-killers: the destroyers of summer, determined to prove that the wild world is a plot against humanity.

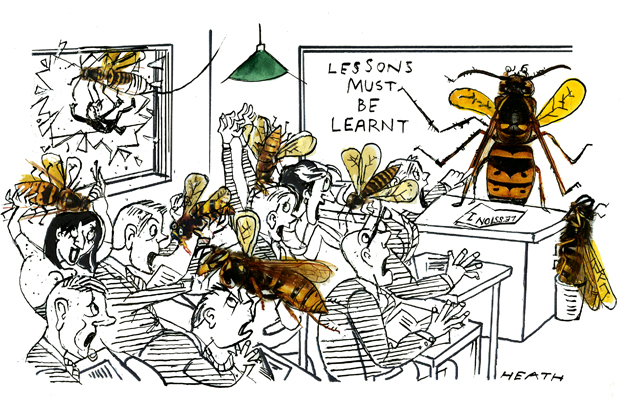

Is there anything good about wasps? Is their sole purpose in life to harass humans seeking the fleeting joys of summer? Does this black-and-yellow air force exist only to ruin the few fine days reluctantly given to us?

If you garden, wasps are among your best friends. The common wasp is a top predator — capturing more than 4 million prey-loads, weighing 7.2lb per acre, every season. Their favourite prey is aphids, rose-killers and tormentors of every gardener’s favourite plants.

Wasps also show many traits we humans admire: loyalty, hard work and sacrifice of the self to a greater cause. The hooliganism they go in for towards the end of the summer is not a fair representation of vespine mores. And more important even than this is the wasps’ contribution to human civilisation. Wasps are responsible for the greatest single shift in our cultural history: like the invention of the internet, but far more radical. If you are reading this in a hard copy, praise the wasps: they are responsible for The Spectator. They are also responsible for Ulysses, Hamlet, The Origin of Species, the Bible, the Quran and Hello! magazine. (Of which more later.) We owe them gratitude, not hard words and flapping hands.

We never see the best of wasps because of the way they act in late summer, when their labour is done. Before that they have led exemplary lives. There are nine species of social wasps in this country, including the much-feared but comparatively mild–mannered hornet, and they’re all honest toilers for most of their existence. Hornets can give a pretty fearsome sting, but you have to go out of your way to experience it. They come into the ancient category of ‘this animal is dangerous — it defends itself when attacked’.

The lives of social wasps are renewed each year when the queens emerge from hibernation in spring, already mated and sated and buzzing with fertility. They seek out a hidden place, an abandoned mammal hole or a crack in a wall or a tree, and build a nest. It will contain around 30 cells and they will lay an egg in each. That nest is highly significant.

When the queen has reared enough workers for the colony, she changes tactic. Now she can concentrate on egg-laying and building extensions to the nest: it’s up to the workers to tend the grubs and they perform their duties assiduously, hunting and feeding… occasionally coming into contact with humans in their search for the nectar and other high-energy food — like Dom Perignon — that they need for themselves.

There is a new generation about every fortnight and a nest can contain more than 5,000 individuals, all in black-and-yellow livery, a striking example of Mullerian mimicry — the tendency of dangerous creatures to resemble each other. It’s a universal warning; threat is always more economical than action.

Eventually, if all goes well, the queen will lay a generation of male drones and queens interested only in sex, though the successful queens will change their minds once they found colonies of their own. Meanwhile, the workers, often with their job in the hive largely done, have little left to do but binge, so out they come like rascals on the spree. All summer long, they were rewarded when they returned to the nest with prey by sugary secretions in the larvae. But when their queen is done — and dead — they are deprived of sugar. We should pity them, claims Paul Hetherington of the conservation charity Buglife, for ‘They are disenfranchised and unemployed addicts. If it’s your picnic they’ve chosen to raid to get their fix, that’s bad luck.’

Next time, perhaps, you can console yourself by considering the wasp’s significance in human culture. To make their nests, wasps chew wood, turn it into pulp and spit it out in a process that creates a structure of hexagonal cells: one of the most exquisite artefacts you can find in the natural world.

Each nest is a small miracle: how do they make it so perfect? How do they keep the walls so straight? How do they make one cell fit into another with such precision? How did the process begin? How long did it take to reach such a level of perfection? A wasp nest is a thing of breathless wonder, and long ago some clever man, staring at one in China, had a eureka moment. He thought: this is not a nest. It’s a letter, a memorandum, an IOU, a billet-doux, a note to the milkman, a contract, a prayer book, the instructions, wisdom, folly, poetry, information, beautiful thoughts and the meaning of life. This is paper.

It happened some time during the Han dynasty, which ended in 220 AD, and naturally the story has been much mythologised. The earliest known bit of paper has been dated between 179 and 41 BC. Paper then spread slowly into the Islamic world and eventually into Europe. Paper was established in Spain in the 12th century and they were manufacturing it in England by the 16th century: infinitely easier than parchment, infinitely cheaper, and not liable to turn back into rawhide when it got wet. So now we could have lots more books. We could transmit knowledge. We could have mass culture.

Wasps changed the way we humans act as a species, but we have seldom shown much gratitude, or for that matter much sense. We have created a series of chemicals that kill invertebrates, never thinking for a second that it’s actually quite a good idea to look after insects. In parts of China they’ve got rid of insects so efficiently that they have to pollinate their fruit trees by hand. Wasps are important pollinators.

Tony Juniper, in his excellent book What Nature Does for Britain, calculates that the services of pollinating insects are worth £400 million a year. It’s really high time we started loving the bloody things. Few people even study them. Their stings mean wasps are among the most under-researched of insects.

But above all, they are a buzzing example of the way we have failed to understand the world we live in. They are part of our past and our present. They created human civilisation and they continue to benefit us in myriad ways. And what’s true of wasps is true of many other living things across in the natural world — the world we recklessly believe is separate from our own.

So next time you encounter a wasp, raise your glass rather than this magazine to a creature that has given us humans so many benefits for 2,000 years and more.

The post What wasps do for us appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in