In 1927, while delivering the lectures that would later be published as Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster made a shy attempt to get to know his Cambridge neighbour, the classical scholar A.E. Housman. At first all appeared to be going well. After one lecture the two men dined together, and Housman told Forster ‘with a twinkle’ that he enjoyed visiting Paris ‘to be in unrespectable company’. Emboldened by this confession, Forster ‘ventured to climb the forbidding staircase’ that led to Housman’s rooms in Trinity College. The door was firmly closed against him. He left a visiting card; it was equally firmly ignored. What might have been the start of a long and happy friendship turned out to be the academic equivalent of a one-night stand.

Such stories still serve as a warning for anyone hoping to get close to Housman — a writer who even his own brother described as ‘shy, proud, reserved, reticent, taciturn, staid, sardonic, secretive,

undemonstrative, and glum’. Biographers face a particular challenge. ‘Nothing very remarkable has happened,’ concludes one of Housman’s early letters, and the curdled regret and relief in that phrase continued to echo throughout his later life, where he took some care to ensure that nothing very remarkable ever happened. Occasionally details surface that suggest a riptide of hidden passions — a list of male prostitutes in Paris, or information about a gondolier in Venice — but these usually turn out to be biographical dead ends.

For a modern critic like Peter Parker, this means having to rely on stories that have been rubbed smooth from handling over the years, such as the list of waspish insults Housman assembled with blanks left for new names to be inserted. Otherwise there is little to report. For decades Housman remained in a groove of his own making, a spiky academic for whom the most interesting long-term relationships were with the dead rather than the living — figures like the Roman poet and astrologer Manilius, who Housman cherished and corrected for many years as he assembled a five-volume edition of the Astronomica. (He also collected erotica like The Whippingham Papers, which suggests where else this taste for loving chastisement may have taken him.) The fact that one of his earliest biographers was named Percy Withers merely adds a comic gloss to what we know about his private life. He was the laureate of repression.

In this context perhaps it is appropriate that the most important event of Housman’s life was one that never really happened. As a student at Oxford, he met a hearty athlete named Moses Jackson, and if Housman’s later poetry gives us any clues (‘I shook his hand, and tore my heart in sunder,/ And went with half my life about my ways’), at some point he told his friend that he wanted to be more than just friends. He was unsuccessful. And for Housman, it seems, first love was the only kind that mattered. His lopsided romantic friendship with the man he called ‘Mo’ (so near and yet so far from ‘Amo’) drifted on but got him nowhere, producing awkwardly bantering letters in which he occasionally peeped out from behind his ironic mask to confess that although he was now a successful academic, ‘I would much rather have followed you round the world and blacked your boots.’ If this is painful to read, one can only imagine what it must have been like to write.

However, what destroyed his chance of personal happiness turned out to be the making of him as a poet. News that Jackson was to travel to India spurred Housman into a purple period of creativity, and in 1896 he published the results as a slim volume of poems: A Shropshire Lad. It was a curious literary hybrid. Seen from one angle, it was a late flowering of romanticism, full of passionate country folk who were forever coming to grief; seen from another angle, it was as spare and taut as an experimental piece of modernism.

The poems were almost wilfully limited in range — ‘May, death, lads, Shropshire’ was Virginia Woolf’s brisk summary — and were crammed with glimpses of things that couldn’t quite be put into words:

The street sounds to the soldiers’ tread,

And out we troop to see:

A single redcoat turns his head,

He turns and looks at me.

Here Housman’s pronouns stage a teasing but elusive drama, as ‘we’, ‘he’ and ‘me’ revolve enquiringly around each other. The repetition of ‘turns’, carried over the line-break, dramatises the speaker’s excited double-take, but the look itself is absolutely neutral. Is it an invitation or a warning? (It is worth remembering that Oscar Wilde had been sentenced for gross indecency only the previous year.) Like so many of Housman’s poems, it leaves us with the impression of fire that has been carefully wrapped in ice.

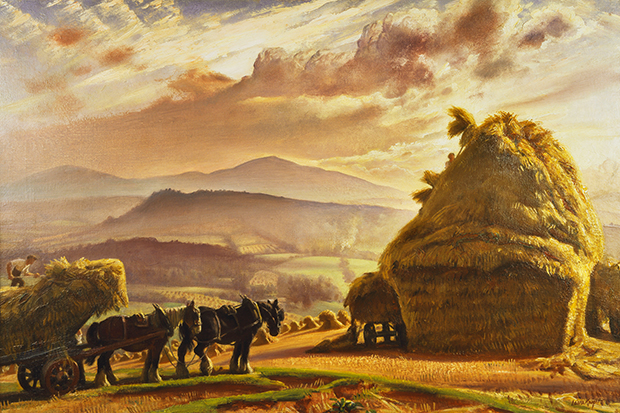

A modest success when first published, within a few years Housman’s poems expressed something far larger than his own private feelings. His ‘land of lost content’ had come to stand for a whole way of life: a rural past that was fast disappearing into folk memory, but had been sealed up by him in poems that were as neat and polished as snow globes. The first world war proved to be an especially important turning point. While recruitment posters pretended that the land British soldiers were fighting for was one of thatched cottages and gently rolling hills, soon cheap editions of A Shropshire Lad were being produced that could fit neatly into an army uniform pocket. They were like little wormholes into a world where death was omni-present (Alan Hollinghurst has described the ‘corpse-strewn landscape’ of Housman’s Shropshire) but the tight structures of the poems kept it firmly in its place. They sold in their thousands.

Soon both of the main words in Housman’s title had become swollen with extra cultural meanings. ‘Shropshire’ represented not just the countryside but the country as a whole: a place of blue remembered hills, where athletes who died young were brought home on the shoulders of their friends, rather than left to rot in the sloppy mud of the trenches. ‘Lad’ was even richer in associations: a word that could suggest a young soldier, but could equally be worked into new poems that took Housman’s homoerotic subtexts and gave them a thrusting life of their own.

Housman would probably have enjoyed these creative ‘aftermaths’ — a word he used in its original, agricultural sense of new growths that appeared in fields after they had been harvested. Although the first part of Parker’s book is centrally concerned with the writing of A Shropshire Lad, it is in the later sections dealing with Housman’s largely undocumented offshoots and outcrops that his writing really comes alive. Literary allusions in writers like Sassoon and Saki, dozens of song settings, crumpled maps of Shropshire thrust into car gloveboxes: Parker is wonderfully alert to the messy reach of these poems in modern culture. Nothing escapes his attention, from ‘Shropshire Lad’ bitter to the impact of Housman’s writing on Morrissey’s mournful games of self-exposure and self-concealment. ‘I thought [Housman’s] poems would be drivel about babies and flowers,’ writes one Smiths fan, ‘but it’s really good stuff about suicide.’

In offering this rich blend of literary criticism and cultural history, Parker proves to be the perfect guide to what he calls ‘Housman Country’, measured and discreetly witty. He is good at offering sharp little asides in brackets, such as the fact that rural labour was often thought to be authentically English ‘(mainly by those who didn’t do it)’, and he also has a talent for elegant phrase-making: ‘because one is lapidary, it does not mean one has a heart of stone… what are cynics if not disappointed romantics?’ Above all, his fine book reminds us why so many readers still have passages of A Shropshire Lad by heart. Housman may not have been very good at expressing his emotions in public — the last postcard he wrote from his Cambridge nursing home in 1936 ended simply ‘Ugh!’ — but when you read about a wounded war veteran who spent his evenings listening to a recording of Vaughan Williams’s setting of ‘Bredon Hill’, ‘playing the record over and over as tears streamed silently down his ruined face’, you realise that he didn’t have to. He had written a book that allowed other people to do it for him.

The post The laureate of repression appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in