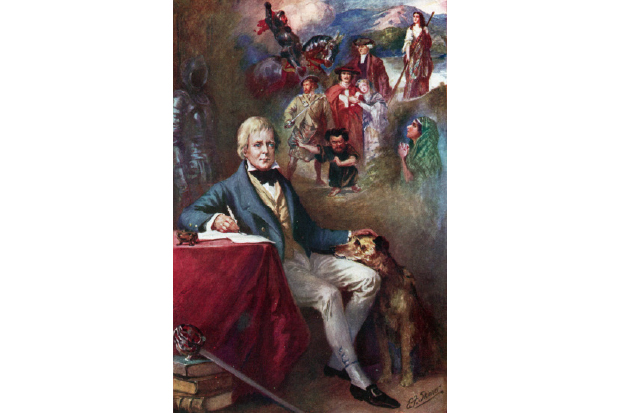

There is an immediate problem for anyone producing a guide to places in Scotland with literary connections: as Walter Scott wrote in Marmion, ‘Nor hill, nor brook we paced along/ But had its legend or its song.’ Many years ago when the Scottish Borders was marketing itself as the ‘Land of Creativity’ I assembled a database of references which stretched to well over 1,000 entries — for example, the village of Yetholm crops up in a strange extended simile in Malcolm Lowry’s posthumous October Ferry to Gabriola.

Then there is Scotland’s propensity for memorialising its own writers. The Scott Monument is only the most obvious example. Within a few miles of where I live there is a memorial plaque to Henry Francis Lyte, writer of ‘Abide With Me’ on Ednam Bridge, a stone’s throw from an obelisk to James Thomson, the poet of The Seasons; a gothic folly on Denholm Green to Scott’s friend and collaborator John Leyden, next to a tablet commemorating James Murray, the first editor of the OED. Depending on the level of granularity, a guide could be as short as a pamphlet or as long as the Chilcot Report.

Finally, this is a crowded field with a long history. Robert Chambers, born in Peebles, was the author of Illustrations of the Author of Waverley in 1822, before he wrote the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation; Professor Alan Riach of the University of Glasgow produced Literary Scotland in 2011; the City of Literature Trust in Edinburgh has produced maps and apps and suchlike.

Garry MacKenzie’s book is cogent and lucidly written and is, I suspect, aimed at readers interested in coming to Scotland rather than students of Scottish literature. The chronology of Scottish literature is broad but accurate. Beginning with the Ruthwell Cross and the Orkneyinga Saga — works written in Anglo-Saxon and Icelandic, not the ‘three languages of Scotland — Scots, English and Gaelic’ so routinely touted by the cultural bureaucrats — it covers medieval, Renaissance, Enlightenment, Victorian, modernist and contemporary Scotland. All the names one would expect are here, although I would have traded references to J.K. Rowling’s coffee-shop-haunting for a nod towards the aforementioned Thomson (the most frequently printed poet in the 18th century), S.R. Crockett — an underrated but enjoyable bridge between Stevenson and Buchan — and some of the contemporaries of MacDiarmid: Robert Garioch’s denunciation of the cultural vandalism in Edinburgh at that period; Sydney Goodsir Smith’s Under the Eildon Tree; perhaps even a nod to the Glasgow canals and Alex Trocchi’s Young Adam, or, for the more squeamish, Dorothy Dunnett.

In terms of the contemporary authors there is more devoted to Alan Warner than Irvine Welsh, which is definitely a good thing; Ian Rankin has a suitably high profile, though perhaps at the expense of Alexander McCall Smith or Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie books; and I might have expected more on Denise Mina’s depictions of Glasgow or William McIlvanney’s Graithrock, his pseudonymous Kilmarnock. Some authors are omitted or mentioned merely en passant — A.L. Kennedy, Allan Massie, Alan Spence, William Boyd — perhaps because they did that all-too-rare thing of not banging on about Scotland the whole time.

The best parts of MacKenzie’s book are the bits where we see ourselves as others see us; in the frequently quoted work of Daniel Defoe, Dorothy Wordsworth, Samuel Johnson and John McPhee. Washington Irving’s hilarious account of being a tourist in Scotland with literary interests would have made a good companion. The praise given to Ian Hamilton Finlay’s garden, Little Sparta, is perhaps not effusive enough and I commend anyone who turns any attention to that miraculous space. And although we get a neatly elbowed-in reference to Game of Thrones — Wester Ross is not actually Westeros, although some of the feuds would frighten Cersei Lannister — there’s nary a word on the books that Tourism Scotland are pinning their hopes on for ‘TV tourism’: I refer of course to Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander.

The post Rich in legend and song appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in