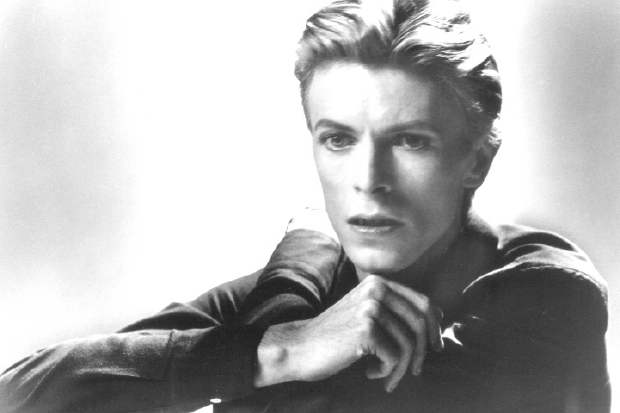

On 11 January 2016 Paul Morley was awoken by an urgent voicemail from the Today Programme. Could he talk about the life and — news just in — the death of David Bowie? (The researcher apologised if this was how he’d heard.) Resistant to gnashing his teeth for a few minutes of radio rent-a-commentary, Morley uncharacteristically ignored this and sundry other requests. Instead he wrote these 500 pages in ten weeks. The same time, he says, that Bowie needed to cut albums at his cocaine-powered peak.

The Age of Bowie is not strictly a biography, with such things as dates and sources and supporting quotations. Want to know about the day Rick Wakeman laid down the piano track for ‘Life on Mars’, or when Robert Fripp blew into Berlin to supply the howling guitar line for ‘Heroes’, or about Tilda Swinton shooting the video to ‘The Stars (Are Out Tonight)’? These and a thousand other nuggets are not here. Between Angie and Iman, no women are mentioned in dispatches apart from one formative lover and Bowie’s mother, who introduces him to Ernest Lough (like Bowie, Morley misnames him Luft). It’s good to know that Bowie had his feather cut dyed at his mum’s favourite salon. But there isn’t much of this pop magazine gossip, nor eyewitness accounts or much sign of original research.

So what is there? Haste — demanded by the type of instant deadline nowadays on-trend in publishing — has encouraged Morley to submit an impressionistic critique of the life as seen through the work. He accepts that his Bowie, the one he first caught live at 15 in Manchester, is his alone, not yours and mine. The collapsible structure he opts for nods to the Dadaist cut-up technique Bowie applied to songwriting. After 70 pages of metatextual throat-clearing, Morley snootily trashes postwar Bromley, where the young David Jones grew up, dwells satisfyingly on Bowie’s hungry years before fame created him, then takes on the changing 1970s year by year (a concept which pretty much breaks down by 1976). Morley’s outro is a bird’s-eye view of the years separating ‘Let’s Dance’ and ‘Blackstar’.

He opens each section with a playful tickertape of gnomic semi-plotted one-liners. ‘David Bowie a face drawn in sand at the end of the sea… David Bowie is groping through the London fog… David Bowie is dancing a furious boredom.’ The more famous facts — when Bowie first looked into the camera on Top of the Pops, when Bowie did that Nazi salute — loiter down byways, awaiting exegesis. There’s a brief sighting of Bowie’s ‘large unruly penis’ but very little on what he did with it.

In theory this paean from an enthusiast is a grand idea. No recording artist better merits semiotic scoping. And though it’s not clear that he ever met Bowie, Morley seems convinced that he’s the pop Boswell for the job; he clears a path for himself by loftily dismissing the work of others: John Wilson of Front Row is duped by a performance; Alan Yentob, who made the seminal Omnibus film Cracked Actor, isn’t even mentioned by name.

Morley’s passion for Bowieana is beyond doubt, as is his intelligent understanding of the work as a spin cycle of inheritances and innovations that endures beyond death. In practice, however, the book reads like the shambolic product of an almighty first-year cultural studies essay crisis. Most dispiriting is the heedless prose. It consists of a Wiki-gush of lists, a motorway pile-up of repetitions, dangling participles, kneejerk alliteration, ungainly gerunds, overburdened prepositions, adverbial clusters, tottering epithets, vacuous assonance. The whole book is strung out on comma splices, and bulky qualifiers (‘a certain’, ‘almost’, ‘somehow’). Bewildering shifts in tense occur sometimes within sentences. The punch which fortuitously paralysed Bowie’s eye ‘embedded an indelible thread of fugitive originality in his appearance’. Please rephrase, you want to scribble in every margin. It’s baffling that a genius whose music is so inspiring has provoked prose bereft of rhythm and style and editorial oversight. The rare quotations from Bowie arrive like sun piercing fog.

There’s quite a bit about Morley himself, much of it rather charming. One of the tidiest sections finds the author sitting in the V&A’s entrance hall at a desk during the David Bowie Is… exhibition he helped to curate, interacting with fellow travellers. They will buy this maddening, baggy homage and find that what was written at the speed of Aladdin Sane is more like the literary twin of 1987’s Glass Spider tour, when Bowie filled the world’s stadiums with baffling clutter so that you didn’t know where to look other than away.

The post Paean to the Starman appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in