Craig Raine is a pugnacious figure in the fractious world of contemporary poetry. When his poem ‘Gatwick’ appeared in the LRB (2015), social media had one of its habitual spasms. Here was a piece which indulged the male gaze and celebrated lustful yearning — an older man for a younger woman. Hardly new ground one might have thought; but to be fair it’s actually rather more subtle than that, and Faber’s former poetry editor responded to the howls of protest by saying: ‘Of course the stupid are always with us.’

In fact Raine rather likes a scrap and My Grandmother’s Glass Eye, in which poets and critics are mauled routinely for their inability to read poems correctly, reminds us that the poet’s father was a boxer. Welcome to the father’s son; he might not float like a butterfly but he can sting like a bee.

The innocuous subtitle — ‘A Look at Poetry’ — belies the purpose of the book. It puts forward an argument which, in its reaching back to the notion that a poem might actually mean something, is both vibrantly derrière-garde and symptomatic of an increasing weariness of post-structuralist theory. Yes, argues Raine, the poet has purposeful intention (we used to call this the intentional fallacy) and, yes, a good reader should be able to grasp the

meaning. Alas, apart from Raine himself, it would appear there’s rather a dearth of good readers:

Bad readers, like the poor, are aways with us. And their badness takes the form of the complacent confusion they bring to poetry. Poetry isn’t diminished by clarity.

Raine the pugilist, the policeman, the preacher and the prosecutor. One of his chapters is called — emblematically — ‘Getting it Wrong’. At some basic level this is a swipe at that sometimes lazy and often convenient anything-goes school of literary criticism. We have become, post-Roland Barthes et al, used to contemplating meanings rather than meaning. Yet Raine becomes Calvinistic in his condemnation of critics who stray from what he perceives as the correct reading. In discussing the not uncomplicated poems of Emily Dickinson, he makes it his business to put the poet-critic Tom Paulin right. The poem in question, in the first example, is ‘He fumbles at your Soul’. Whereas Raine tells us without hesitation that ‘He, the subject, is death’, Paulin vaunts ‘his feminist credentials’, thus ‘turning Dickinson’s poem into a peevish, spinsterish complaint about men and their ways’; and later, now discussing Dickinson’s ‘I never lost as much as twice’ Raine describes Paulin’s ‘reading of this simple poem’ (he sees it as a love lyric) as ‘a perverse miracle of misprision’.

Animus and erudition and not a hint of self-doubt. It is rather like having a ring-side seat where the punches are only going in one direction. (Please, someone ring the bell!) Raine’s argument against the allure of ambiguity, a sort of reworking of practical criticism with Leavisite certainty, situates his brief in a wider, anti-theoretical and very English context. Literary theory has largely been a European import — with its phalanxes of French intellectuals — and in his recent piece in the TLS (‘The slow, uncertain death of post-structuralism’, 10 June) Terry Eagleton wryly noted that ‘Postgraduate students could accumulate valuable cultural capital by

demonstrating that a literary work meant five or six incompatible things at the same time.’

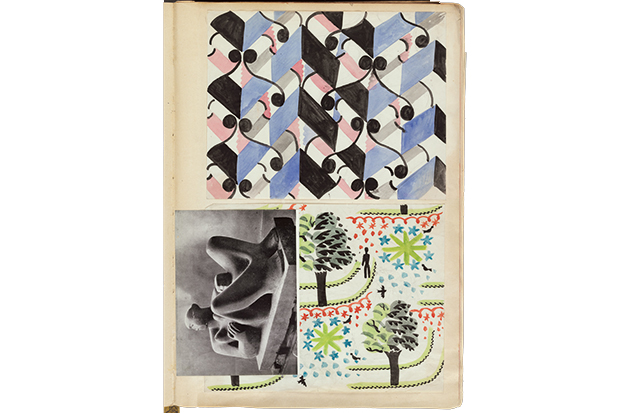

Raine’s poetic is partly formed by T.S. Eliot, whose Four Quartets (1944) could be seen as the curtailing of experimental modernism. Raine has little time for American poets such as John Ashbery, whose poems are difficult to read. How would he read Frederick Seidel? Post-1945, English poetry, thanks to Larkin and the Movement and Philip Hobsbaum and the Group, distanced itself from international modernism, re-establishing the English line and privileging form and meaning. Ezra Pound had called for the smashing up of the iambic pentameter. The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry (1982) championed the ludic, and by then Raine’s A Martian Sends a Postcard Home, with its figurative verve, had inspired a voguish new way of writing. Its foundational poem, however, is a code which can be easily broken by careful close reading; its artifice is a common territory shared by poet and reader. It makes sense — ‘the Movement plus fireworks’. English poetry, with its pragmatism and sense of tradition, has not surrendered to Derrida’s ‘metaphysics of presence’. Grandmother’s glass eye might have been squinting at the referendum.

The post Preacher and prosecutor appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in