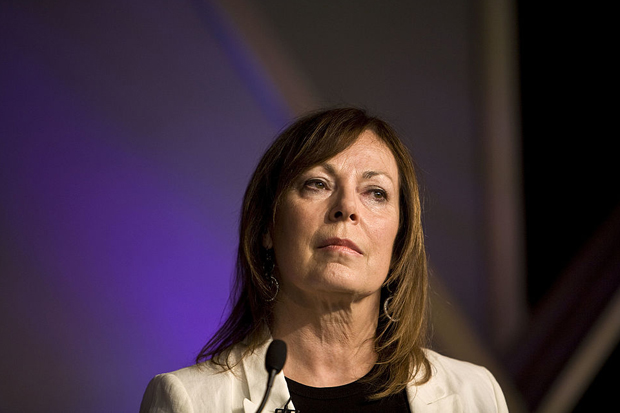

‘How can you come into this room and ask me “What is the purpose of life?”,’ wails Massive Attack’s laconic DJ Mushroom after a typically searching interrogation by the veteran music journalist Sylvia Patterson. In this powerful, enjoyable memoir she fares better with Spike Milligan (‘I wake up every morning and think, “Thank God, another day” ’) and gleans further nuggets of wisdom from the likes of Bono, Diana Ross and David Attenborough. Patterson, primarily an interviewer rather than a critic, isn’t interested in the mechanics of music-making or the record industry but in the fundamental question of why people do what they do. In her hands, music journalism becomes a philosophical investigation, with jokes. Always jokes.

Patterson made her name at the sorely missed pop gazette Smash Hits during its 1980s heyday and still writes under the influence of its conspiratorial intimacy and playful one-liners: Morrissey’s ‘bilious haverings’, acid-house crew D Mob’s ‘yodelsome rave-up palaver’, Prince’s ‘atomic ripple of fawn and mauve’. In his memoir Rock Stars Stole My Life, the former deputy editor Mark Ellen describes Smash Hits as ‘a fond, full-colour mission to squeeze the maximum amount of fun out of everything’. To the wry, confident Ellen it is a brilliant lark but to Patterson the magazine’s madcap exuberance is a matter of life and death.

She takes seriously the escapism of pop because she had a lot to escape. She grew up in Perth with an alcoholic mother, who became ‘Somebody Else Entirely’ when she was drinking and inflicted lifelong scars. Moving to London to take a job at Smash Hits in 1986 is Patterson’s version of running off to join the circus: ‘Life was euphoric.’ Music, to her, is a transcendent miracle and the people who make it are characters in an absurdist soap opera. Her richly entertaining encounters with the likes of Madonna, Blur, Eminem and Amy Winehouse are interleaved with episodes of grief and chaos, including vampiric boyfriends, financial disaster, a string of bereavements and a gruesome drunken injury that almost cost her her right arm. The contrast is occasionally surreal: she sensed the first signs of a miscarriage while interviewing Mariah Carey in a massage chair.

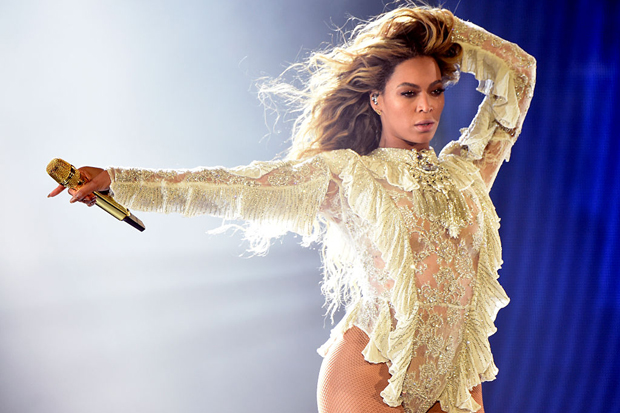

The rewritten interviews illustrate Patterson’s audacious sense of fun, with many questions eliciting a snort of disbelieving laughter. No one else, I suspect, would ask the impeccable Beyoncé the old Smash Hits favourite, ‘Have you ever been sick all down your cleavage?’ (No, unsurprisingly.) She is unapologetically partisan, with a burning passion for bright, opinionated stars like Jarvis Cocker and Noel Gallagher. If, on the other hand, you’re snide, bullying, humourless or, God forbid, dull then ‘(Snip!)’ — as Smash Hits used to say. Patterson’s interview with the militantly tedious Westlife amounts to banging her head against a beige wall. ‘What’s the point of you, do you think?’ she asks. ‘We like to sing,’ says one of the Boring Ones.

Unfortunately, Westlife won and the book gradually takes on an angry, mournful tone. Patterson’s first boss, at the shortlived (and misspelt) Dundee magazine Etcetra, condensed the secret of success into ‘K.I.S.S.: Keep It Simple for the Stupids.’ The magazines that Patterson loved scoffed at such cynicism, but Smash Hits, The Face and The Word are gone, NME is a shrivelled husk and K.I.S.S. reigns supreme. A crueller, shallower media breeds paranoid, overprotected pop stars too scared to be interesting. After Patterson is sucked into a bruising and unnecessary online dust-up over an interview with the band Warpaint, she rages: ‘We live in spineless, reactionary and hideously po-faced times.’

Is this just the jaundiced nostalgia of middle age? I don’t think so. The music industry has indeed become more timid and conservative, journalism more desperate, the carefree fun of Smash Hits unimaginable. Every music journalist old and lucky enough to have experienced a more liberated era feels the walls closing in. In particular, Patterson’s style of interviewing — energetic, open-hearted, risk-taking, provocative — has become almost impossible. She closes her book with an appreciation for life undiminished and her accumulated wisdom put to good use (it turns out that Bono and Spike Milligan were right all along), but it’s still a crying shame.

In Patterson’s unsent resignation email to NME in 2001, reprinted here, she decries the lack of ‘love or poetry or art or depth or compassion’ in the new world of music journalism. For those who feel likewise, it is no small consolation to read a book that overflows with those qualities.

The post Escape into pop appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in