‘Hidden beauty is best (half seen), faces turned away.’ So noted a young English painter named Winifred Knights in 1924. Until recently, the power of her own work has been thoroughly concealed. After her death in 1947, indeed even before it, Knights was forgotten. By the 1950s her reputation had sunk so completely that both the Tate and the Fitzwilliam Museum refused to accept one of her masterpieces as a gift.

However, artists who disappear into oblivion are sometimes rediscovered — and that is what has happened to Knights, who is now the subject of an admirable exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery. It is, as the cliché goes, a revelation.

One of the things it reveals is how English painters continued to love the Italian Renaissance well into the modernist era. Knights’ art was an intense, almost hallucinatory reworking of the Quattrocento — but in the aftermath of the first world war and the age of surrealism.

Born in 1899 in Streatham, Knights studied at the Slade School of Art. At 21 she won a scholarship to the British School at Rome — the first woman student ever to do so. The winning painting was ‘The Deluge’ (1920), her best known, and indeed only well known, work since it was purchased by the Tate in 1989. It depicts Noah’s flood but is populated by modern figures wearing skirts, trousers and waistcoats. However, this strange and visionary picture is full of early Italian echoes. The angular silhouettes of the people fleeing the rising waters are derived from Carpaccio; the terrified woman who turns to look behind as she runs from the rising waters is taken from Fra Angelico. At the Slade — like so many of the best British artists of the early 20th century, from Paul Nash to Stanley Spencer — Knights was taught by Henry Tonks, who believed that ‘the classic tradition of drawing’ was born in 15th century Italy and ended with Degas, taking in rather few other artists in between. You can see the Tonks training in the fastidious clarity of her drawings. But there was also something else in her finest pictures, something personal — a weird stillness.

In the early 1920s, which she spent in Rome and the Italian countryside, Knights produced a handful of intense and idiosyncratic paintings. The picture turned down by the Fitzwilliam and Tate — and finally accept by the Museum of New Zealand, Wellington — depicted ‘The Marriage at Cana’ (1923). It shows the biblical scene, however, as though revisited in a dream. The guests, seated at long tables in contemporary dress, are mostly female. Knights herself appears three times.

In front of them are set slices of watermelon, each section of the spherical fruit represented with geometric precision, the pink of the flesh inside singing out — a perfectly pitched note of colour. Behind is a woodland based on the Borghese gardens — the tree trunks receding like pillars in a church — which could have been the setting for a panel by Uccello.

Knights wasn’t alone in her allegiance to the 15th century. Long after her lifetime, Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico continued to fascinate British painters. David Hockney has mentioned his great admiration for both. You can see the strong Angelico yellows, pinks and oranges in the new portrait cycle on show at the Royal Academy. The late Euan Uglow, too, was a lover of Piero. He had, indeed, a good deal in common with Knights. Each aimed for an extreme precision of forms; those slices of watermelon could be so many still life pictures by Uglow. They also both worked with enormous deliberation.

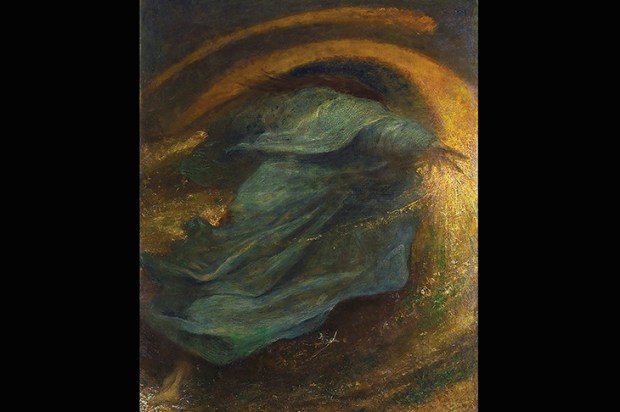

Uglow would take years over a painting, and preferred to describe them as ‘stopped’ rather than ‘finished’. Knights seems to have got slower as time went on, and finally more or less stopped herself a decade and a half before her death. Her last two major works, ‘The Santissima Trinita’ (1924–30) (pictured on p29) and the ‘Scenes from the Life of Saint Martin of Tours’ (c.1928–33), took respectively six and five years to complete. After the second, she did little more until her death 14 years later — still only in her late forties — from a brain tumour.

The book by Sacha Llewellyn accompanying the Dulwich exhibition connects this drying up with the birth of her child in 1934. Perhaps Knights, as an artist, was a victim of marriage and motherhood — often the enemies of female talent in those days. But there is a slightly airless, post Pre Raphaelite quality about ‘Saint Martin of Tours’ that suggests her inspiration was already running out. It lasted for only a few years, as it sometimes does with artists and writers. But in her finest work you can see she was, simultaneously, a lover of Piero and a member of the same generation as Salvador Dalí.

The post Echoes of Italy appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in