Laid out flat, running the length of the exhibition, the original scroll of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road forms the spine of the large Beat Generation show at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Even for those familiar with the published version of the manuscript seeing this holy relic — the founding document for all sects of Beat worshippers — is a powerful experience. For about a minute. It’s everything else — the movies, the posters, the paraphernalia — that takes the time and generates an exhibition on such a tremendous scale. But how could it not sprawl? You start with the writers — Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs — and before you know it there’s jazz, Neal Cassady, the Merry Pranksters, acid, you name it.

And there are, of course, a lot of photographs. No literary movement or group generated as many impressive photographs. Burroughs and Ginsberg took a bunch of photographs of themselves and their friends. And Kerouac is assured a cameo role in the larger history of the medium by virtue of the essay he contributed to Robert Frank’s The Americans. Frank’s work — both his photographs and the tedious film Pull My Daisy — is featured in the show and he himself crops up in a number of photographs taken by others. That’s the repeated motif of the exhibition and the movement to which it is devoted: the makers of the documents are themselves documented — often in the process of making their documents. Ensemble photographs featuring the main players are imbued with the conviction that they would become stars in a firmament of their own creation. We have a wealth of documentary evidence of the formation of a myth whose power endures to this day.

But always one comes back to Kerouac. For two reasons. Because he was the most important writer — on the basis, for me, of a single book. And because there has never been a better-looking male writer. The Kerouac of the 1950s — athletic, muscular forearms emerging from plaid shirt, dark hair roughly quiffed — could step into a bar in Brooklyn today and he’d still look hip. But how quickly images of the author at his peak give way to evidence of collapse. It proved impossible to remain more than an instant at the summit Kerouac had laboured so hard to achieve.

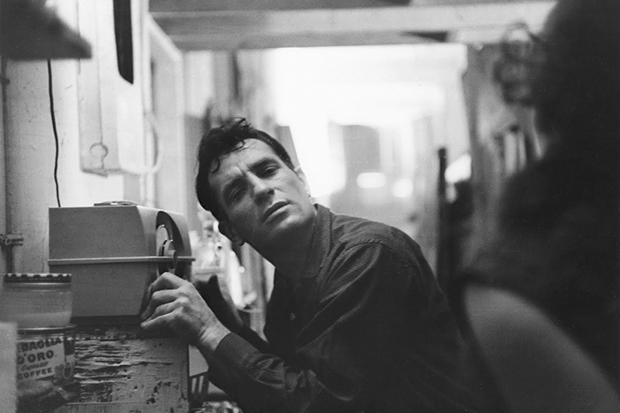

This picture was taken by John Cohen in 1959, a couple of years after On the Road had finally been published. During the years of its composition — and in the face of multiple hostile rejections from publishers — Kerouac was convinced that his ‘great novel’ would ‘gain its due recognition, in time, as the first or one of the first modern prose books in America’. He was right. Lionised, adored, imitated, he changed the course not only of literature but of society at large. But the long wait took its toll. From the moment his achievement was recognised his talent was in decline. He became imprisoned by the method of composition — spontaneous prose — that had liberated him. The breakthrough that enabled him to become a great writer condemned him to often being a pretty terrible one. Sinking into alcoholism, living with his mum in Florida and Massachusetts, he became ‘a big glooby blob of sad blufush’.

Cohen’s picture of Kerouac tuning in to listen to himself on the radio captures not just a moment but the whole of the life; not just the man but the legend — and vice–versa. He’s listening to himself, to a record of his own achievement. It’s something every aspiring writer dreams of. But you also feel he’s trying to locate what has been lost, partly by success, partly just by age, partly because it could only be powered by the enormous hunger brought on by rejection. His voice is there but, unable to actively create it, he can only replay and rewind it. Condemned to living out his life in the wake of his legend, he is trying to find again the voice that is fading even as it is remembered, as it echoes in memory. Gesturally, visually, the echoes are of his younger self hunched over the typewriter banging out his bop prosody, or of pianist Bill Evans over the keyboard.

It’s poignant and beautiful, because while for Kerouac the echoes are from the past, they were in the process of being transmitted to the future via the radio in some lonesome boy’s bedroom, filling him with the thought of adventure — not just the kicks of being on the road but the adventure of becoming a writer. You can hear it in the lines of the Springsteen song ‘Dancing in the Dark’ when he sings ‘I’m sick of sitting round here trying to write this book.’ Not just any book but — implicitly — this great book. Kerouac’s ambition, hope and hunger live on. The romance — and doom — of that will never die. You can see it. You can hear it.

The post Beat echoes appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in