In Notting Hill Gate, in west London, the division was obvious. On the east side of the street was a row of privately owned Victorian terraced houses painted in pastel colours like different flavoured ice creams. These houses, worth £4 million to £6 million each, were dotted with Remain posters. On the west side was a sad-looking inter-war council block, Nottingwood House, which had dirty bricks and outside staircases and corridors. No posters there. But that is where my fellow campaigners and I headed — down to the basement entrances with their heavy steel gates. We looked up the names on the canvassing sheets and rang the bell of one flat after another until we found someone who would buzz us in. This was the hunting ground for the Leave campaign.

The referendum revealed a great divide in Britain. According to YouGov polling, the overwhelming majority of university graduates — 70 per cent — were for Remain. But among those with nothing above some GCSEs, a similarly big majority — 68 per cent — were for Leave. The highest social classes were for Remain (62 per cent). The lowest were for Leave (63 per cent).

There was also a city versus country divide. Parts of London were well over 70 per cent for Remain, whereas country areas — particularly on the coast — were for Leave.

Every election is divisive, but none has pitted rich against poor like this one. The social divide has been far more dramatic than the divide between the two main political parties. In general elections, the professional and managerial classes favour the Tories by a margin of four to three. The difference is nothing like as marked as the social divide in the referendum vote. As a generalisation, the split has been between the educated ‘haves’ on one side and the working class on the other. The Remainers found ways of making this point — casting themselves as cosmopolitan and ‘open’ against the crude and (presumably) closed-minded Leavers.

I came across quite a bit of scornful self-righteousness among the rich Remainers. In one street of private houses, a woman repeatedly shouted at us: ‘You’re all bonkers! Get out! You are not wanted here!’ A prosperous-looking man at the doorway of his private house informed us that immigration was a good thing and was economically necessary: the implication being that those who seek controlled immigration are both anti-immigrant and ignorant of the economics of the matter. His irritated parting shot was: ‘I hope you lose!’

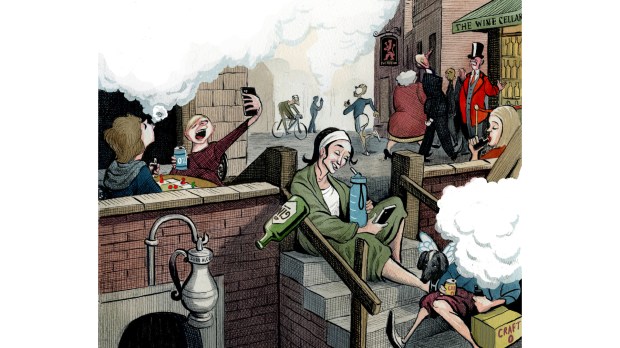

The divide shows how changes brought about by globalisation and large-scale immigration have affected different classes in contrasting ways. For the ‘haves’, it has been a boon. The Notting Hill crowd now has cheap, highly qualified Polish builders, well-educated Polish cleaners and perhaps a Romanian nanny for their children. They go to Caffè Nero and are served by polite Italians. They feel deliciously international and open-minded while enjoying cheaper, better services than they otherwise would. When they arrive at Pisa airport for their holiday in Tuscany, they join the EU queue for passport control and feel part of a cosmopolitan club.

Without looking at the detail, the ‘haves’ readily believed the forecasts of the Treasury and others that leaving the EU would damage the economy. They looked down on Nigel Farage and thought how, by not being on his side, they demonstrated that they were not racists. They were global-minded, not Little Englanders.

One Remain poster suggested that to be for Remain was to be ‘kind’, ‘open’, ‘inclusive’ and ‘tolerant’ which, of course, implies the opposite about Leave. Yet some of the Remainers I met while out campaigning were anything but tolerant. After feeling their contempt a number of times, I got to the point of thinking: ‘Oh God! I hope we don’t have to knock on any more doors of the bloody haute bourgeoisie!’ I got far more grief from them than in the council blocks.

I offered car stickers to drivers at a junction, and soon worked out who the takers would be. There was no point bothering with Porsche Cayennes driven by elegant ladies. At the other end of the spectrum was Gladys, who I met at the door of her council house on Monday. She was reluctant at first to say which way she was voting. She got her council house in 1975 after two years waiting for it. But now she worries for her sons and grandchildren. How are they going to afford somewhere to live? The cost of mortgages just goes up and up, she said.

There is precious little chance of council housing. Immigrants have helped increase the demand while the supply has stagnated. So where were her grandchildren going to live? Her son was waiting in accident and emergency recently. Waiting and waiting. Ahead of him was someone for whom a translator had to be found. She didn’t want people to think she was a racist. But she evidently felt that this was her country and her family was being squeezed out of housing and having to jostle for care from an NHS that was overstretched, in part, by the large and sudden influx of immigrants. Getting the children into a good state school was also a problem.

Gladys was not xenophobic or racist. What bothers her isn’t immigration, as such, but the government’s inability to respond to immigration and the resulting shortage of housing and school and hospital places. The rich folk across the road could get round these problems. Hector and Harriet could go to a private school if necessary. If there was a two-week wait to see their NHS GP, they could go private. They have already got their own flat or house, which has gone up nicely in value, thank you very much.

I can’t help suspecting that part of the contempt of the ‘haves’ was fuelled by knowing ‘I’m all right, Jack!’ although, of course, they would never admit it. The European Union has worked out very well for them — and, to be honest, for me. And (knowing the demographics of those who read current affairs magazines) probably for you too. This is why it’s odd when David Cameron urges older voters to think of their grandchildren: they do that anyway. What he should be doing instead is asking wealthy voters to consider those who compete with immigrants for jobs: those who are heavily dependent on the welfare state for housing, healthcare and education.

There is no wallet-powered escape route for the working classes. They are trapped. Their lives are damaged. They are also the ones who have to compete with the Poles, Romanians, Croatians and so on for the low-paid jobs. The wages paid to those in skilled trades are down more than 10 per cent over the last six years. Again, this may be a net economic benefit, meaning lower prices, greater corporate profits and more tax on those profits. But we ought not to forget those for whom it means lower wages.

There is danger in all this. We have seen in Greece the rise of a far-left government. In Spain, there is a similar upsurge. In France, Marine Le Pen and the Front National are closer to power than at any time previously. In Britain, the anger of the ‘have-nots’ has so far been contained — probably because unemployment has been kept down. But it would only take mismanagement of welfare benefits and an excessively high national living wage to change that.

When David Cameron was re-elected last year, he committed himself to a ‘one-nation Conservatism’. And yet the campaign he has just led has shown up the divide in Britain, pitting one side against the other. Disraeli never used the phrase ‘one nation’, but in his novel Sybil he did refer to the two nations: the rich and the poor. Nations, he wrote, ‘between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones’. These are the two worlds I’ve seen on the campaign trail over the last few weeks.

We ought not to ignore, or sneer at, those who feel this process leaves them (and their families) behind. Soon, Britain’s £9 minimum wage will rise above the average wage in several EU countries, which, if Britain had chosen to remain in the EU. would have attracted even more immigration over an indefinite period. A situation that is already bad for ‘have-nots’ would now be on course to get progressively worse. And with that would have come an increasing sense that no one in power cares about what life is like for them. Britain is a divided nation and that should concern the elite a great deal more than it has so far.

The post Britain’s great divide appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in