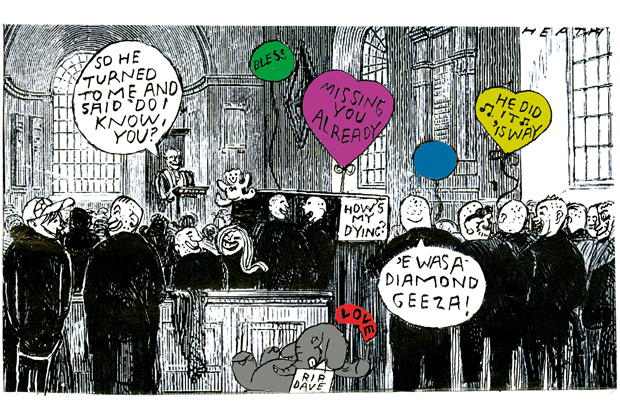

Funerals ain’t what they used to be. Today’s emphasis is more on celebrating a life past than honouring the future of a soul. While I am not averse to a celebratory element, the funeral is morphing into a spiritually weightless bless-fest. This was brought home to me last week at the funeral of Enid, a lady I knew only through our mutual attendance at bingo in the community centre.

I was uncomfortable from the moment we gathered outside the church, where my sombre suit set me apart from the Technicolor crowd of family and friends. The atmosphere was more akin to a wedding, even a hen do, than a funeral, the air drenched in perfume and aftershave. Inside, there was pew-to-pew chatter, wall-to-wall music (Robbie Williams’s ‘Angels’, inevitably), not a single moment of silence, and not a single sacred song, let alone a prayer (an inaccurately mumbled Lord’s Prayer excepted). There were two readings, one by a grand-niece of perhaps eight, snivelling, bless, a poem about being only next door; then a nephew offering a eulogy, the main point of which was that his aunt had been a keen gardener ‘and she will plant her flowers in heaven’.

I know I shouldn’t sneer. Religion, the Anglican version anyhow, is a broad church with a wide liturgical spectrum. But I could not help feeling that such celebration missed the point. It somehow connected with a virtual life rather than a real death. It was spiritual displacement activity.

As someone already in the queue, so to speak, I can see why this is becoming the norm. Social media declares that privacy is theft: your life is public property. The same must apply to death. And yet selfie culture insists, ‘Look at me, I’m having a wonderful time.’ It is uncomfortable with any performance conflicting with that message. Grief falls into this category.

One means of resolving the contradiction is the memorial service. Originally reserved for civic and media nobility — and there has been an epidemic of such sad departures recently — it has now become fashionable for more local heroes. Such services occur substantially post-mortem, enabling a style of celebration that might be perceived as distasteful if indulged during the actual funeral service. Another option is to forego the funeral entirely through ‘instant cremation’: the deceased is taken direct from the deathbed to disposal at the crematorium. Finally, there is the fashion for heaping flowers on memorial benches and accident locations rather than at the grave.

In each case, the effect is to devalue the funereal act. Does it matter? The decline of the religious funeral is symptom of a cultural malaise — one infecting even those services with a traditional liturgy of prayer and Bible readings, where too often the president admonishes the congregation to avoid sadness, presumptuously invoking the deceased’s authority: ‘Enid would not want your tears.’

Well, sorry, but when it is my turn — and it could be any day now — I do want tears. I have no wish for a eulogy, and certainly not one which reduces my three score years and twenty to an aptitude for horticulture, but I expect some recognition that I will leave a gap: that in simple, silly ways I shall be missed.

This plea is made as much on behalf of those in attendance and those left behind as it is for myself. The funeral is a universal social construct, based on an ancient formula for the healthy expression of collective grief. But it is more than that. It nudges us all into an amendment of life. It offers liturgical material which reassures us that the man with the scythe will not have the last word. Because, whatever our beliefs, the reality is that the death of another is a shock and the religious funeral — which places the event within a more cosmic dimension — is an essential part of the therapy for the traumatic distress which will invariably follow.

As it happens, I attended a better funeral a couple of weeks earlier. It took place in a crematorium, whereas Enid’s affair had been in a real church. So in a sense the contrast was the greater. We sat in silence until the coffin was brought in with those wondrous ominous words

I am the Resurrection and the Life…

which set the tone for a sustained focus on the divinity of love and the hope of eternal life. Even without the accoutrements of a holy building, there was a feeling of belonging to a larger universe, a sense of the transformational.

In this secular age, sceptical of the numinous, the religious funeral demands from us the spiritual literacy which can surrender its cerebral convictions to an incredible hope. If that ingredient is removed, if every departure is presented as an event from which we are urged to move on, to draw a line under, then it does not take a psychiatrist or a theologian to identify a major source of contemporary angst.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in