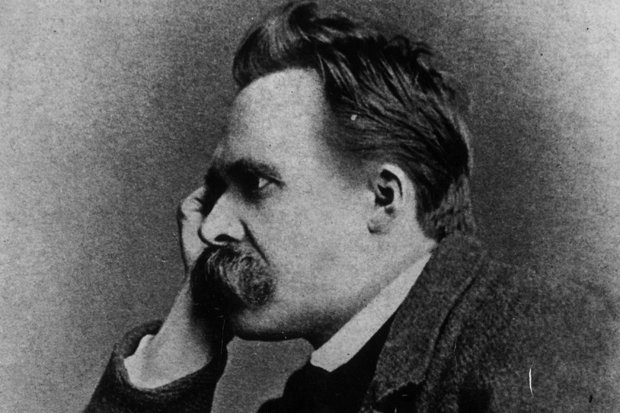

When Friedrich Nietzsche was offered a professorship in classical philology at the university of Basel in 1869 he was so happy he burst into song. He was only 24 at the time — a year younger than Enoch Powell, who became a professor of Greek at the university of Sydney aged 25 — and looked forward to a brilliant academic career.

Three years later, when he delivered the six lectures contained in this book, he was already showing signs of disillusionment. His teaching duties included six hours at the local gymnasium — the German equivalent of a secondary school — and he wasn’t impressed by what he found there. To anyone who’s followed the debate about failing standards in Britain’s schools that dates back to the publication of the first ‘Black Papers’ in 1969 and probably long before that, Nietzsche’s complaints will have a familiar ring to them.

The teachers possess ‘limited gifts’, the students are of a ‘low level’ and the curriculum owes far too much to ‘the plebeian “culture pages” of magazines and newspapers’. Nietzsche is particularly incensed by the claims of the gymnasiums to be providing a classical education — or should that be gymnasia?

‘I have never once found in the German gymnasium a single gossamer thread of anything that can truly be called “classical education”,’ he harrumphs. It’s all a far cry from the ‘true education’ he received — although, unusually for someone looking back at his own schooldays through rose-tinted spectacles, Nietzsche is talking about a Golden Age that existed less than ten years earlier.

The fundamental problem, according to the philosopher, is that German secondary schools have expanded too quickly in an attempt to keep pace with the growing demand for state functionaries. They’re trying to educate too many people, rather than the intellectual elite, and this has inevitably led to the emergence of ridiculous, progressive ideas about the intellectual abilities of ordinary students.

He complains:

They treat every student as being capable of literature, as allowed to have opinions about the most serious people and things, whereas true education will strive with all its might precisely to suppress this ridiculous claim to independence of judgment on the part of the young person, imposing instead strict obedience to the sceptre of the genius.

Phrases like ‘the sceptre of the genius’ crop up often in Anti-Education and it’s not hard to detect the seeds of the Übermensch — an anti-Christian superman who will revitalise the German volk. As fans of Nietzsche will know, his sister Elisabeth edited his works to enable the Nazis to claim him as an intellectual forebear, but she won’t have needed much red ink here. In passage after passage, Nietzsche exalts the grandeur of ‘the German spirit’, whether expressed through the German Reformation, German music, ‘the tremendous courage and rigour of German philosophy’ or, most ominously of all, ‘the German soldier’.

When Nietzsche complains about the decline of German secondary education, he doesn’t just mean that insufficient deference is shown to the Greek poets and philosophers, but also to Goethe and Schiller, particularly their command of language. ‘Everyone nowadays automatically speaks and writes in a German so vulgar and bad that it could only exist in an age of newspaper German,’ he scoffs, one of several disparaging references to journalism. ‘A true purification and renewal of the gymnasium can proceed only from a deep and violent purification and renewal of the German spirit.’

Much of Anti-Education is taken up with these bombastic calls to arms and you can imagine his audience sniggering at the spectacle of an excitable 27-year-old

decrying the decline of German education; but it would be wrong to dismiss it out of hand. At its heart, the book contains a powerful critique of the principle of universal public education that was soon to become established in modern democracies all over the world. Given the cost to the public purse, isn’t it inevitable that the aims of education will become subordinate to those of the state? And if schools are expected to educate all children, not just those of exceptional ability, how do you avoid the debasement of the curriculum?

If these issues continue to be debated today, as they surely are, that is partly because the questions posed by Nietzsche in these six lectures have yet to receive any satisfactory answers.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £8.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in