One day, in the autumn of 1960, a young Frenchman launched himself off a garden wall in a suburban street to the south of Paris. He jumped in an unusual away; not as if he expected to land, feet first on the pavement below, nor even as if he were diving into water, but arms outstretched, back arched, apparently taking off into the air above. The result was Yves Klein’s ‘Le Saut dans le vide’ (Leap into the Void), which opens the exhibition Performing for the Camera at Tate Modern.

Beside the finished product — a photomontage — are two other images that together explain how it was done. One shows the same quiet stretch of road, completely empty except for a solitary cyclist passing by like an extra in a Maigret dramatisation. The other shows the flying artist behaving in that apparently impractical fashion, but with, instead of a hard landing, five man holding a tarpaulin underneath him. So this is a trick, a fake — or, to put it another way, a work of art.

Yves Klein’s ‘Le Saut dans la vide’

The distinction is, after all, a bit hazy. We all presume that Caravaggio, for example, did not actually see a young man sprouting wings fluttering in the air and whispering words of divine inspiration into the ear of St Matthew. On the other hand, if photographers present us with images of events that did not occur — or would not have happened had the photographers not arranged for them to do so — they may be greeted with muttered criticisms such as ‘staged’.

Klein brilliantly exploited this zone of ambiguity. Is his leap a performance, a joke, a metaphor or a philosophical observation about the nature of art? Probably, the answer is: all of those. It is certainly, unusually for a photograph, so memorable that the whole picture pops into mind, like a slide, if you close your eyes.

In this respect, ‘Leap into the Void’ is highly unrepresentative of Performing for the Camera. In aggregate, the exhibition is wearyingly enormous and bemusingly dull, full of large white rooms stuffed with small black, grey and white snaps of subjects such as naked hippies having a happening in New York in the Sixties or people doing something obscurely conceptual involving traffic in Tokyo around the same time. In other words, here is a prime example of curatorial overkill: an exhibition that is far too large for its subject.

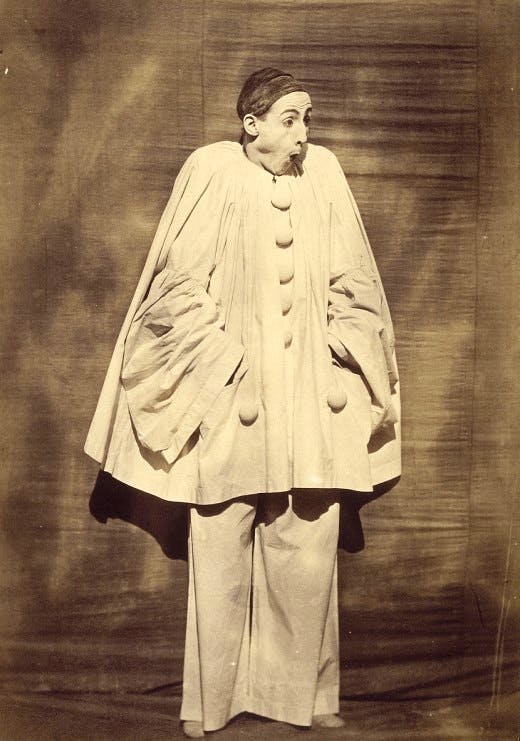

Nadar’s photograph of Charles Deburau

It does, however, make some interesting points. One is that a great deal of art — and photography — is staged or, if you prefer, ‘faked’, and always has been. A Rembrandt self-portrait is a carefully conceived presentation of the artist, and so, too, is — among many such artist’s selfies on display — Marcel Duchamp in drag as his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy or Joseph Beuys explaining art to a dead hare. The same is true of many images that are often placed in the history of ‘photography’ rather than ‘art’, such as Nadar’s beautiful shots from 1854 of the mime artist Charles Deburau, in costume and striking poses from his act.

A far better exhibition, at the V&A, is devoted to the American photographer Paul Strand. This is beautifully mounted and selected, but it gives rise to some of the same thoughts. Strand (1890–1976) was, ostensibly at least, one of the leading modernist photographers of the 20th century. His work adhered to a puritanical aesthetic — no colour, no glitz, lots of workers, plants and elderly buildings among his subjects.

In 1916 Strand captured some of the least ‘staged’ pictures ever taken, using a specially doctored camera with a fake lens on the side, which seemed to point straight ahead while Strand shot surreptitiously under his arm. Thus he was able to obtain something that is hard to achieve: close-ups of strangers in the street who were not aware they were being photographed. The results bring you very near to passers-by on New York’s Lower East Side a century ago — jowly, red-faced, grubby-looking types who could have come out of a painting by Hals or a novel by Dickens. These were seen and shot in an instant, true snapshots — a hunting term first used by Sir John Herschel, one of the great unsung progenitors of photography.

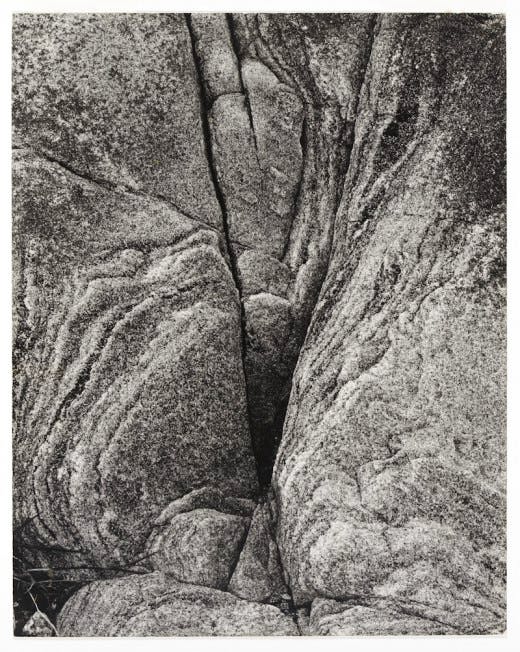

Paul Strand’s ‘Rock, Loch Eynort, South Uist, Hebrides’ (1954)

In another sense, of course, these were not spontaneous at all. Strand must have known just what he was looking for, and probably had precedents from paintings and literature at the back of his mind. In any case, as the catalogue points out, Strand clearly found this predatory way of working unsettling, and stopped after taking just a handful of these extraordinary portraits. Most of his work was meticulously programmed and choreographed, the product of sittings that lasted hours, and much more time spent in the developing room on the prints.

This is the justification for an exhibition such as this — that the actual photographs, like an original painting, have a quality that reproductions lack. They do; but they are still small, dark pictures spaced out on a wall. You wonder whether Strand’s work does not really look better in a book, such as the splendid catalogue.

This could not be said of the works on show in Avedon Warhol at Gagosian, 6–24 Britannia Street, London WC1. Neither Warhol nor Avedon, a remarkable photographer of people, could be accused of puritanism or lack of glitz. The Warhol ingredients here are familiar, demonstrating how he was able to return much of the oomph of painting to photographic images by adding splashy silk-screened colour.

More of a surprise are some of the Avedons, especially ‘Andy Warhol and Members of the Factory, New York, October 30, 1969’, a photographic group portrait on the scale of life — it’s almost four metres across — in which the central group are nude, looking a little like Greek statues. The picture is as artfully posed as a Caravaggio, and all the better for it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in