The Fitzwilliam Museum is marking its bicentenary with an exhibition that takes its title from Agatha Christie: Death on the Nile. But it turns out it was another writer of a different type of fiction who was directly involved. M.R. James, author of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, amassed some of the exhibits in his capacity as director of the Fitzwilliam from 1893 to 1908. And almost any object on display would have made a perfect prop for one of his tales, because the subject is ancient Egyptian coffins.

Generally, the main character in a story by James is a retiring gentleman scholar who comes across a venerable item which then brings upon him some diabolic haunting or curse. He did not actually write a narrative beginning with a curator who receives an ornately decorated 3,000-year-old casket from a burial site in Middle Egypt. But in real life, James did negotiate the Fitzwilliam’s acquisition of several fabulous items on show in Death on the Nile.

Among these are the cedarwood box, from around 1,900 bc, which once contained the mummy of a woman named Nakht, described as ‘lady of the house’. It is, as is sometimes the case with Egyptian antiquities, weirdly well-preserved. The timber — an expensive, imported item which seems to have been recycled — is almost completely intact. On one side the paintwork has been damaged by water, but elsewhere the hieroglyphic inscriptions and depictions of palace façades are fresh and almost jaunty.

It is true, as a text in the exhibition argues, that the ancient Egyptian obsession with death was in fact a preoccupation with life — and how to prolong it in the afterlife. That is why the tomb of a man called Khety from 2010–1950 bc contained miniature sculptures of workers baking, butchering a cow, filling a granary and sailing boats on which Khety could travel on the river. Inscriptions on his coffin (also acquired by James) ask the gods Osiris and Anubis to provide offerings for him to use. Evidently, the plan was for Khety to have a comfortable time in the hereafter.

Nonetheless, there is something eerie about Egyptian grave goods. Partly, this is to do with their preservation. Our sense of age is connected to normal rates of decay, so we are not used to seeing wooden and cloth objects, thousands of years old, that look only slightly battered. The other thing that’s a little uncanny is that all these carvings, pictures and painted inscriptions were not intended to be seen by living eyes at all, but by those of the gods and the dead. It is quite easy to imagine James penning a disturbing narrative — his are the most haunting of ghost stories — entitled ‘The Coffin of Nakht’.

The exhibition, most of which comes from the Fitzwilliam’s own collection, is evidence of how rich in diverse masterpieces the museum is. A display entitled Celebrating the First 200 Years illustrates some of its history. The founder, Richard, 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam (1745–1816), was an engaging Irish aristocrat who was responsible for developing a section of Georgian Dublin. He was also a harpsichordist and spent time in Paris, where he met the love of his life, a ballerina who went by the name of Mademoiselle Zacharie. When Lord Fitzwilliam died, apparently as the result of a fall from his library steps — a thoroughly M.R. Jamesian accident, by the way — he left his old master paintings, drawings, medieval manuscripts, books and musical scores to Cambridge University (he was an old Trinity Hall man).

The last exhibit in Death on the Nile, chronologically, is a mummy with, at its top, a naturalistic portrait in the manner of ancient Greek painters. It’s a marvellous example of cultural fusion, and also a reminder that portraiture can be a monument to the dead. The same point is made in a different way by Russia and the Arts: The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky at the National Portrait Gallery. Made up of loans from the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, this contains portrayals of just about anyone who was notable in Russian literature and music between the mid-19th century and the first world war. Artistically it comes down — as perhaps the culture of Tsarist Russia itself does — to an array of great writers and composers.

They are all there, often painted in a realist, almost photorealist mode that seems to bring these people from long ago and far away very close (which is, of course, the feat of time travel a good portrait can perform). Tolstoy was painted by Nikolai Ge in 1884 at his opulent desk, frowning with concentration in the very act of writing. As painted by Vasily Perov, Dostoevsky seems to shrink into himself, melancholy but filled with inner tension.

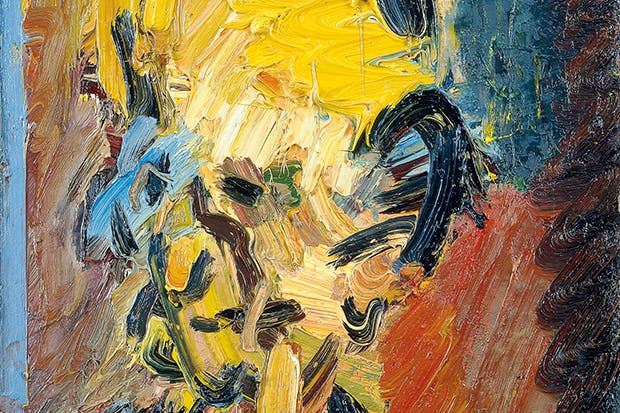

Most memorable of all is Ilya Repin’s 1881 portrait of Modest Musorgsky: a picture of a man contemplating his own demise. This was painted in the Nikolaevsky Military Hospital, where the musician, a chronic alcoholic, had been admitted. It records Musorgsky’s rosy drinker’s nose and reflective demeanour. According to Repin, he was living ‘under a strict regime of sobriety’, but still dreaming of booze. Eventually, an attendant smuggled in a bottle of cognac. The next day, Repin arrived to find his sitter, aged 42, was no longer among the living. A case, you might say, of death on the Neva.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in